Peter Paul Rubens DPG43

DPG43 – Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia (or Horn of Plenty, previously known as Ceres and Two Nymphs)

c. 1625–8; panel, 30.9 x 24.4 cm

PROVENANCE

?Estate of P. P. Rubens, 1640, Antwerp, no. 164, Een stuk van dry Nymphen met den horne des Overvloeds;1 Vne piece de trois Nymphes auec la Corne d’abondance or A peice with some Nymphes with a Cornucopia;2 ?P. J. Snyers sale, Antwerp, 23 May 1758 (Lugt 1008), lot 47;3 ?Michael Bryan sale, London, Coxe, 17 May 1798 (Lugt 5764), lot 40;4 Insurance 1804, no. 123 (‘Cornucopia; Rubens; £100’); Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 23, no. 229 (‘Drawing Room / no. 17, Three Nymphs with fruit – sketch – P[anel] Rubens’; 1'8" x 1'10").

REFERENCES

Terwesten 1770, p. 201, no. 11;5 Cat. 1817, p. 8, no. 135 (‘SECOND ROOM – West side; The Goddess Pomona; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 383, no. 135;6 Cat. 1820, p. 8, no. 135 (Pomona – Rubens); Cat. 1830, no. 171 (The Goddess Pomona); Jameson 1842, ii, p. 470, no. 171;7 Denning 1858, no. 171; Denning 1859, no. 171 (The Goddess Pomona. A Sketch); Lavice 1867, p. 181 (Rubens no. 8);8 Sparkes 1876, p. 151, no. 171;9 Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 141, no. 171 (Rubens; A sketch for a large picture); Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), p. 133, no. 651-I (Three Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty, Related works, no. 1a, is by Rubens and Snijders); Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 10, no. 43; Rooses 1903, p. 438 (Three Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty);10 Dillon 1909, pp. 151, 215 (Three Nymphs with Fruit); Cook 1914, p. 25, no. 43 (‘Three Women with a Cornucopia’); Oldenbourg 1921, pp. 126, 459, under Related works, no. 1a (c. 1615–17; DPG43 is an original); Cook 1926, p. 24, no. 43; B. 1932, pp. 377 (fig.), 410;11 Grossmann 1948, pp. 53–4 (fig. 38); Cat. 1953, p. 35; Paintings 1954, pp. 16, [60]; Willoch 1973, p. 178, under no. 420 (Related works, no. 1d); Díaz Padrón 1975, i, pp. 321–2, ii, p. 202 (fig.), under no. 1664 (Related works, no. 1a; Rubens and Snijders); Díaz Padrón 1977, p. 127, no. 114 (Related works, no. 1a; Rubens and Snijders); Hermann-Fiore 1979, p. 120 (about Related works, no. 1a); Murray 1980a, p. 112, no. 43 (Ceres and Two Nymphs with a Cornucopia); Murray 1980b, p. 25; Held 1980, i, pp. 344–5, no. 255 (c. 1625–7; Nymphs filling the Horn of Plenty; wrongly as DPG171), ii, pl. 256; Lecaldano 1980, i, p. 132, no. 294 (c. 1616); M. Vandenven in Van de Velde 1982, p. 116, under no. 52 (Related works, no. 2b.I); Jaffé 1989, pp. 230–31, no. 440 (c. 1617); Muller 1989, p. 123 (note 3); Robels 1989, pp. 128, 374–5, under no. 280 (Related works. no. 1a; c. 1625–8); p. 513, under no. AZ 133 (Related works, no. 2b.I);12 Kockelberg & Huvenne 1993, p. 182, under Related works, no. 2d;13 Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, p. 1094, under no. 1664 (Related works, no. 1a; Rubens and Snijders; Ceres and two Nymphs); Beresford 1998, p. 208 (Ceres (?) and Two Nymphs and a Cornucopia); White 2008, p. 48; Tyers 2014, pp. 16–18 (the image is in reverse); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 194–5, 213; Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 100–103, no. 18; Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 131–3, no. 8a (Abundantia – Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia; c. 1625–8), ii, fig. 58; RKD, no. 184420: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/184420 (Aug. 13, 2019).

EXHIBITIONS

London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 44 (L. Burchard);14 Rotterdam 1953–4, p. 83, no. 70, pl. 59 (E. Haverkamp-Begemann; Prado picture perhaps with Snijders); London 1977, pp. 139–40, no. 185 (J. Rowlands; Ceres); Japan 1999, p. 167, no. 23 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 132–3, no. 38 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Greenwich, Conn./Cincinnati, O./Berkeley, Calif. 2004, pp. 180–83, no. 23 (P. C. Sutton; 1625–8; fig. in reverse); Brussels 2007–8, pp. 123–4, no. 29 (C. Van Mulders); Madrid/Rotterdam 2018–19, pp. 100–103, no. 18.

TECHNICAL NOTES

Three-member oak panel, with bevelling along the verso edges. Dendrochronology gives a terminus post quem for the panel of after 1609. There are two small retouched splits at the bottom of the left member, and a gouge on the reverse in the central panel. The paint is generally thinly applied, with some areas of impasto, particularly in the fruit and around the hair of the central figure. The paint on the outer members has leached. The under-modelling in the flesh is a little thin and worn. There is some sharp craquelure towards the bottom left corner and on the cheek of the left-hand figure. Some of the old restorations appear discoloured and matt. Previous recorded treatment: 1873, frame regilded; 1967, new frame after burglary.

RELATED WORKS

1a) Prime version: Peter Paul Rubens (and assistant), and Frans Snijders, Abundantia; Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty (previously Ceres and Two Nymphs), c. 1625–8, canvas, 224.5 x 166 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1664 [1].15

1b) Copy of 1a: Studio of Peter Paul Rubens, Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty, canvas, 207 x 153 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Christie’s, New York, 9 June 2010, lot 259; Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, New York, 2005–7; Sotheby’s, New York, 27 Jan. 2005, lot 130; Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Ala., 1961–2005).16

1c) Copy after 1a or 1b, or another copy, in reverse: Theodor van Kessel, Abundance (Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty), 1652–60, inscriptions, etching with some engraving, 430 x 324 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-47.663 [2].17

1d) Attributed to the studio of Rubens, Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty (Ceres and Pomona), after c. 1628, canvas, 150 x 119.5 cm. Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, 1353.18

1e) (between DPG43 and 1a) Copy after a modello for 1a?, drawing, present whereabouts unknown. Photo RKD [3].19

1f) Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces with Fruit, 3 ft by 2 ft 6 in.20

1g) copy after Peter Paul Rubens (1a), Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia, canvas, 222 x 142 cm. Formerly Sanssouci, Potsdam, GK I 7592, lost in WWII.21

Details of 1a

2a) Rubens’s Cantoor (unknown artist) after 1a (?), Two Nymphs, before 1628 or after?, red chalk, 317 x 281 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, KKSgb7889, Rubens’s Cantoor, I, 23 [4].22

2b.I) (preparatory drawing?) ?Frans Snijders, A Parrot, before 1628 or after?, coloured chalk, 186 x 146 mm. BvB, Rotterdam, V16.23

2b.II) Rubens’s Cantoor (Willem Panneels or Frans Snijders?) after 1a and 2d, Study with a parrot and a monkey, before or after 1628, colour inscriptions, black and red chalk, 165 x 260 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, KKSgb7939; Rubens’s Cantoor I, 24 [5].24

2c) Follower of Rubens, A Parrot, c. 1630–40, panel, 46.9 x 37.7 cm. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, P.1947.LF.385.25

2d) Peter Paul Rubens, Madonna with a Parrot, c. 1614–17, 1630–33, panel, 163 x 189 cm. KMSK, Antwerp, 312.26

2e) Roman copy of a Greek 4th-century BC or early Hellenistic Muse, adapted as a Nereid, Nereid mounted on a Hippocamp. Uffizi, Florence [6].27

Pendant

3a) Modello for 3b.I: Peter Paul Rubens, Satyr squeezing Grapes with a Tiger and a Leopard, c. 1616–18, panel, 33.4 x 24.2 cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, A 153; WA1855.28

3b.I) (paired with 1a since 1636) Peter Paul Rubens, Satyr squeezing Grapes with a Tiger and two Infant Satyrs. Present whereabouts unknown (New Room or Hall of Mirrors, Alcázar, Madrid, in 1636 and 1659).29

3b.II) Copy after 3b.I: Workshop of Rubens, Satyr squeezing Grapes with a Tiger and two Infant Satyrs, canvas, 220 x 148 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Dresden, 1578.30

Similar compositions

I. Titian

4a) Titian, Diana and Actaeon, c. 1556–9, canvas, 184.5 x 202.2 cm. NG, London, NG6611, and NGS, Edinburgh.31

4b) Peter Paul Rubens after Titian, Female Nude and Female Heads, 1628, black and red chalk, heightened with white on light grey-brown paper, 449 x 289 mm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 82.GB.140 [7].32

II. Achelous

4c.I) Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel I, The Feast of Achelous, c. 1615, panel, 108 x 163.8 cm. MMA, New York, Gift of Alvin and Irwin Untermyer, in memory of their parents, 1945, 45.141 [8].33

4c.II) Abraham Janssens I, Naiads filling the Horn of Achelous, c. 1616–17, canvas, 108.5 x 172.5 cm. Seattle Art Museum, 72.F.37/J2675.1.34

4c.III) Abraham Janssens I, Naiads filling the Horn of Achelous. Allegory of the Peace of the Twelve Years’ Truce, c. 1610, canvas, 118 x 97 cm. KMSKB, Brussels, 12162.35

4c.IV) Jacques Jordaens, Achelous defeated by Hercules. The Origin of the Cornucopia (Allegory of Abundance), dated 1649, canvas, 245 x 311 cm. SMK, Copenhagen, KMSsp233.36

III. Ceres

4d.I) Modello: Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders (?), Homage to Ceres, c. 1614, panel, 90.5 x 65.5 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, GE 504.37

4d.II) Modello: Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders (?), Homage to Ceres, 1614–15, panel, 91 x 66 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Dorotheum, Vienna, 21 April 2010, lot. 27; Hermann Beyeler collection, Lucerne (Switzerland)).38

4d.III) Jan Saenredam after Hendrick Goltzius, Ceres (from the series Ceres, Venus and Cupid and Bacchus), 1596, inscriptions in Latin, engraving, 450 x 323 mm. BM, London, 1850,1214.49.39

4d.IV) Jacques Jordaens, Homage to Ceres, c. 1619, canvas, 165 x 112 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1547.40

4d.V) Cornelis Schut, Bacchus, Ceres and Pomona, inscriptions, etching, 241 (cropped) x 180 mm (cropped) in an oval. BM, London, 1859,0611.160 [9].41

IV. Diana

4e) Peter Paul Rubens, Diana and Callisto, c. 1635, canvas, 202.6 x 325 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1671.42

V. Nature, Abundance, Earth

4f.I) Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel I, Nature veiled by the Three Graces, surrounded by a festoon of fruit, c. 1614–16, panel, 106.7 x 72.4 cm. Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow, 609.43

4f.II) Modello: Peter Paul Rubens (?), Coronation of Abundance (or of Peace), panel, 49.5 x 35.5 cm, c. 1620–22. Galleria dell’Accademia nazionale di San Luca, Rome, 307.44

4f.III.a) Modello for 4.f.III.b: Peter Paul Rubens, The Union of Earth and Water (The River Scheldt and Antwerp), c. 1618, panel, 35 x 30.5 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 267.45

4f.III.b) Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders, The Union of Earth and Water (The River Scheldt and Antwerp), c. 1618, canvas, 222.5 x 180.5 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, 464.46

VI. Nymphs with or without satyrs

4g.I) Copy after Peter Paul Rubens: Nymphs and Satyrs (Allegory of Fertility). Present whereabouts unknown (J. L. Menke collection, Antwerp).47

4g.II) Jan Brueghel I and workshop of Peter Paul Rubens, Nymphs filling the Cornucopia, c. 1615, panel, 67.5 x 107 cm. MH, The Hague, 234.48

4g.III) Peter Paul Rubens, Nymphs and Satyrs, c. 1615, 1638–40, canvas, 139.7 x 167 cm. Prado, Madrid, P1666.49

Collaboration with Frans Snijders

5a) Modello for 5b: Peter Paul Rubens, The Recognition of Philopoemen, c. 1609, panel, 50 x 66.5 cm. Louvre, Paris, MI 967.50

5b) Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders, The Recognition of Philopoemen, c. 1609, canvas, 201 x 311 cm. Prado, Madrid, P1851.51

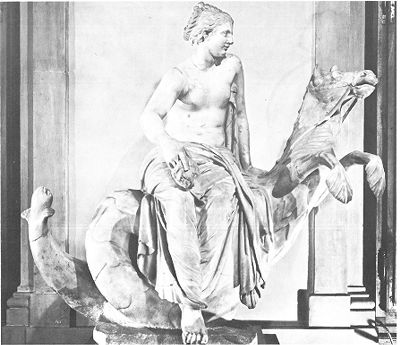

DPG43

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia, c. 1625-1628

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG43

1

Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders and Paul de Vos

Abundantia (Three nymphs with a Cornucopia), c. 1625-1628

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P 1664

2

Theodorus van Kessel after Peter Paul Rubens

Abundance (Nymphs with the Horn of Plenty), 1652-1660

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-47.663

3

after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Nymphs, c. 1628

Whereabouts unknown

4

after Peter Paul Rubens

Two Nymphs, 1628-1630

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KKSgb7889, Rubens’s Cantoor, I, 23

5

after Peter Paul Rubens

Study of a parrot and a monkey, before 1628

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KKSgb7939; Rubens’s Cantoor I, 24

6

Anonymous, Roman

Muse, adapted as a Nereid

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi

7

Peter Paul Rubens after Tiziano

Studies of women, 1628

Los Angeles (California), Malibu (California), J. Paul Getty Museum, inv./cat.nr. 82.GB.140

8

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel (I) possibly studio of Peter Paul Rubens

Feast of Achelous, 1614-1615

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 45.141

9

Cornelis Schut (I)

Bacchus, Ceres and Pomona

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1859,0611.160

A small-scale sketch, DPG43 is regarded as a preparatory work for the large-scale painting by Rubens in the Prado (Related works, no. 1a) [1]. The latter is one of eight pictures ordered for King Philip IV of Spain, which Rubens probably took with him on his diplomatic mission to Madrid in 1628.52 According to Orso the eight pictures formed four pairs, and they should be interpreted as symbolic references to the virtues of the Spanish rulers. In the New Room (or Hall of Mirrors) of the Alcázar Palace in Madrid the Three Nymphs with the Horn of Plenty was paired with a Satyr squeezing Grapes, in which two young satyrs and a tiger are also visible (Related works, no. 3b.I).53 This Satyr picture is only known from copies, of which the best is in Dresden (Related works, no. 3b.II), and from the modello in Oxford (Related works, no. 3a). The pair appear in palace inventories in 1636 and in 1659.54 Orso interprets this pair as a reference to abundance, which is the result of good government. According to Vergara the sexual symbolism of the cornucopia underscores its use as a symbol of abundance.55 Not much is known about this commission, so it is unclear whether the subjects of the pictures were Rubens’s idea or prescribed by the Spanish patron or his intermediary in Flanders, the Infanta Isabella. In any case the price had been agreed upon before the pictures were painted: Rubens was paid 7,500 florins for the eight pictures.56 DPG43 was dated rather early by Oldenbourg (c. 1615–17) and Jaffé (c. 1617), but Held and Burchard suggested a date c. 1625–7; Rooses dated the Prado picture to about 1628, and consequently DPG43 shortly before that.57 It seems more plausible that the paintings Rubens took to Madrid were ones he had recently finished.

There are many differences between the modello and the Prado picture in the appearance and poses of the figures (only the nymph on the right is practically unchanged), the landscape setting, and the additional fruit, parrots and monkey. The figure on the left has become a brunette goddess instead of a blonde who looks like a Flemish farmer’s daughter, and her right arm is no longer reaching to the top of the cornucopia but in her lap, where there are two corncobs inside their husks. She holds one of them. The standing, fully clothed, figure on the right seems ennobled, just as the nymph on the left is. Rubens indicated the fruit on the floor and in the cornucopia in DPG43, but in the Prado picture a parrot, a flying parakeet, a monkey and a tree are added. The parrot is eating from the horn of plenty, and the monkey sitting on the floor is eating from the fruit. Since Rooses in 1903 all Rubens scholars seem to agree that the fruit and the animals in the Prado picture were painted by Frans Snijders, although that animal painter is not mentioned in the oldest Spanish sources, or on the print by Theodor van Kessel (c. 1620–after 1660; Related works, no. 1c) [2]. There we only find Rubens’s name as inventor.58 Robels in her Snijders monograph (1989) is not quite sure.59 In the Prado picture she misses the technical perfection that is usual for Snijders’ painting of fruit; she attributes this to the tight deadline he might have been working to as a consequence of Rubens’s trip to Madrid in 1628. According to her, the landscape (and the tree?) by Rubens himself look unfinished.60 Alejandro Vergara, however, considers that the landscape is finished, but very damaged on the left side of the painting.61 Held in his 1980 volumes about Rubens’s oil sketches does not mention Snijders for the Prado picture, although at least since 1975 in the Prado catalogues the name of Frans Snijders appears as collaborator. In any case Rubens is known to have collaborated with Snijders from the time of The Recognition of Philopoemen (c. 1609–10), for which he made a very detailed sketch, now in the Louvre (Related works, nos 5a–b). There Rubens indicated clearly what the still life was to look like; Snijders however made some small changes and added some objects, for instance carrots in the upper centre, changes that are comparable to the changes between DPG43 and the Prado picture. According to Vergara the fruit and the animals are painted in a style typical of Snijders.62

Interestingly the parrot, the flying parakeet and the monkey are depicted in one of the drawings in Rubens’s Cantoor in Copenhagen (Related works, no. 2b.II) [5], which were mostly copies made by Rubens’s pupil Willem Panneels. If the drawing was after the Prado painting, it must have been made before Rubens left for Spain in 1628 with his eight pictures for the King. However another picture with the same subject, Three Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty, was still in Rubens’s possession in 1640, when he died (see Provenance). According to Held that was DPG43, but the parrot, parakeet and monkey are not visible there, so that could not be the source for Panneels’s drawing.63 Recently Nils Büttner affirmed that none of the painted (20) and drawn (4) copies, or the print by Van Kessel, is an exact copy of the prime version now in the Prado; they had as model a copy after the Prado picture (Büttner’s copy no. 1) or the picture that was still in Rubens’s possession in 1640 (his no. 9), if that is not DPG43.64

The Cantoor drawings in Copenhagen also include another drawing of the same (?) parrot. This one however was copied after Rubens’s The Holy Family with a Parrot (Related works, no. 2d), which Rubens painted for the Guild of St Luke in Antwerp in two stages: the middle part c. 1614–17, and the extensions to the left (where Rubens depicted the parrot) and to the right c. 1630 or before. Rubens gave the picture to the Guild in 1633 when he was appointed dean. We can safely assume that he finished it without assistance, since such pictures were supposed to display the abilities of the member of the Guild. Clearly Rubens was quite capable of painting animals, even a parrot, so it is not completely unthinkable that he himself painted the parrot and other animals in the Prado picture of Three Nymphs with a Horn of Plenty.

In another of the Cantoor drawings the two nymphs are copied (Related works, no. 2a) [4]. Strangely enough, the one on the left has her arms in the same position as in the Prado picture, but her face and hair look more like the blonde in DPG43 than the brunette in Madrid or in the copies (such as Related works, nos 1b and 1d). Was there yet another picture with nymphs after which the drawing was made, or did Rubens change the head in the Prado picture between Antwerp and Madrid? There is another Rubens related drawing, known only from a photograph at the RKD; according to Robels it might be a copy after a Rubens sketch that has disappeared, since it could not have been made after the finished picture: the fruit drawn in the upper part looks like that in DPG43, and there are no animals or fruit on the ground (Related works, no. 1e) [2].65 The young woman on the right is however shown frontally with one of her breasts bared, and she is looking out at the viewer, in contrast to the one in DPG43 (fully clothed and seen in profile) or the one in the Prado picture (also fully clothed, also seen sideways, but with her face in three-quarter view).66

The 1636 inventory of the New Room in the Alcázar describes the Prado picture as showing Ceres and two nymphs, and although the goddess indeed holds two corncobs (not unusual for Ceres, the goddess of agriculture), she is probably not what Rubens intended. In 1980 Held made a strong case for identifying the supposed Ceres with a naiad or water nymph. For this he refers to the picture by Rubens and Jan Bruegel I with the Feast of Achelous now in New York, where on the left we see a group of three naiads or water nymphs, two of them filling the horn of plenty and one of them rising from the water (Related works, no. 4c.I [8].; see below for the story of Achelous and the origin of the cornucopia or horn of plenty). It is quite possible that Rubens was referring to this story in DPG43 and the Prado picture, but the poses of the three naiads in the Feast of Achelous are different. Kieser in 1933 noted that for the pose of the left figure in the Prado picture Rubens took inspiration from the Roman marble Nereid mounted on a Hippocamp (Uffizi, Florence); in the 16th century she was believed to be Cymothoë, one of the fifty daughters of Nereus and Doris (Related works, no. 2e) [6].

In Spain Rubens’s interest was caught by the so-called poesie of Titian, such as Diana and Actaeon, then in the Spanish royal collection and now shared between the National Gallery in London and the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, after which Rubens made a drawing of the servant looking down who is drying the leg of Diana (Related works, nos 4a–b) [7]. He also studied the intricate hairstyles with braids, which we find in DPG43 and the Prado picture. The pose of the servant is similar to that of the nymph on the right in DPG43 and the Prado picture. Both before and after this composition Rubens conceived scenes with crouching and seated women attending to Diana, as in the scene of Diana and Callisto in the Prado of c. 1635 (Related works, no. 4e). The figures are not confined to scenes with Diana: see below for compositions with nymphs and satyrs (Related works, nos 4g.I–III).

The story of the cornucopia or horn of plenty comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (IX.1–88; translated by John Gay, 1712).67 Here the river god Achelous, entertaining the Greek prince Theseus to a meal in his cave, tells how he had fought Hercules three times. On the third occasion he had transformed himself into a bull, but Hercules broke off one of his horns, which the naiads filled with fruits and flowers:

From my maim’d front he tore the stubborn horn:

This, heap’d with flow’rs, and fruits, the Naiads bear,

Sacred to plenty, and the bounteous year.

He spoke; when lo, a beauteous nymph appears,

Girt like Diana’s train, with flowing hairs;

The horn she brings in which all Autumn’s stor’d,

And ruddy apples for the second board.

This horn was then brought to the meal with Theseus, again filled with flowers and fruit, making it into a horn of plenty, as depicted by Rubens and Jan Brueghel I, c. 1615 (Related works, no. 4c.I) [8]. In this picture Rubens shows not one naiad (rising from the water with flowing hair) as Ovid says but two more, standing and busy filling the horn of plenty. Interestingly, above the naiads two parrots can be seen, similar to the one in the Prado picture. Apparently both Brueghel here and Snijders in the Prado picture (or was it Rubens in both cases?) thought it was appropriate to combine nymphs with parrots.68

Cornucopias were associated in Antiquity with Abundantia (Abundance) and Fortuna (Good Fortune).69 More recent depictions, as in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1603), associate them with agriculture, concord, fertility, rivers and regions, autumn, and the Golden Age. As a consequence cornucopias became connected with scenes of the Good Government (of a ruler) and Peace (see for instance Rubens’s Minerva protects Pax from Mars (Peace and War) in the National Gallery, London: DPG285, Related works, no. 2b). The cornucopia came to be associated with a large number of deities, including Ceres and her daughter Pomona, the name given to the female figure on the left of DPG43 in the early Dulwich catalogues. Pomona was the daughter of Ceres and Neptune; most of the images where she is depicted show her with Vertumnus; in some she is with her mother Ceres, as in a print by Cornelis Schut I (1597–1655; Related works, no. 4d.V) [9], where Bacchus is also included. Ceres is shown with a cornucopia, but both Ceres and Pomona have their heads decorated with ears of corn (see also under DPG165; Related works, nos 7–9).

Rubens made pictures which certainly depict Ceres. In the modelli in the Hermitage and Lucerne (Related works, nos 4d.I–II) she is a statue, fully clothed, which Rubens borrowed from an Antique sculpture from the Borghese collection, Rome.70 At that time in the Netherlands when Ceres was not depicted as a statue she was accompanied not only by a horn of plenty but also with a scythe and with decorative headgear made from ears of corn.71 That is how we see her in a print by Jan Saenredam (c. 1565/6–1607) after Hendrick Goltzius (Related works, no. 4d.III), and somewhat later in a picture with a very statuesque Ceres by Jacques Jordaens (Related works, no. 4d.IV). So Ceres is sometimes accompanied by a horn of plenty. But so too is Abundance,72 in the Coronation of Abundance of c. 1620–22 (Related works, no. 4f.II), which depicts a sitting and a standing female nude crowning Abundantia with a cornucopia in the centre. Earth (or Antwerp) is provided with a cornucopia in The Union between Earth and Water (Related works, nos 4f.III.a–b), as is the Venus Frigida in Antwerp (see under DPG165, Related works, no. 5; Fig.).

Rubens made several compositions of nymphs with a cornucopia with satyrs, such as the early picture now called Allegory of Fertility (disappeared; Related works, no. 4g.I). There he seems to combine the two scenes of which he made two separate paintings for the Spanish King in 1628, one with nymphs and one with satyrs (Related works, nos 1a [1], and 3b.I). He made a very similar composition much later, in a picture in the Prado (Related works, no. 4g.III). The figures Rubens invented there appear in other pictures with many variations, as in a picture in the Mauritshuis and one in Glasgow, both collaborations between Jan Brueghel I and (the workshop of) Rubens (Related works, nos 4g.II and 4f.I). In the latter case the figures appear in the part below; the central theme (three Graces or nymphs adorning Nature) will be considered under DPG264.

DPG43

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia, c. 1625-1628

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG43

1

Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders and Paul de Vos

Abundantia (Three nymphs with a Cornucopia), c. 1625-1628

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P 1664

2

Theodorus van Kessel after Peter Paul Rubens

Abundance (Nymphs with the Horn of Plenty), 1652-1660

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-47.663

3

after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Nymphs, c. 1628

Whereabouts unknown

4

after Peter Paul Rubens

Two Nymphs, 1628-1630

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KKSgb7889, Rubens’s Cantoor, I, 23

5

after Peter Paul Rubens

Study of a parrot and a monkey, before 1628

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KKSgb7939; Rubens’s Cantoor I, 24

7

Peter Paul Rubens after Tiziano

Studies of women, 1628

Los Angeles (California), Malibu (California), J. Paul Getty Museum, inv./cat.nr. 82.GB.140

8

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel (I) possibly studio of Peter Paul Rubens

Feast of Achelous, 1614-1615

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 45.141

9

Cornelis Schut (I)

Bacchus, Ceres and Pomona

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1859,0611.160

Notes

1 Denucé 1932, p. 63, no. 164; this piece is supposed to have been sold to Philip IV of Spain 1640–45 for 740 florins (Génard 1865–6, p. 85: Item nog een stuck van dry nimphen, metten […] van abondantien (note 1: une pièce de trois nymphes avec la corne d’abondance, no. 164 […] end of note), geteeckent no 164, vercocht voor, ƒ 740’, as quoted by Muller 1989, p. 123 no. 164. This picture seems to have been lost in Spain.

2 Belkin & Healy 2004, p. 331, no. 164; Muller 1989, p. 123, no. 164: this was previously thought to be the Prado picture (Related works, no. 1a), but that was already in the Spanish Royal Collection by 1636. According to Muller the picture mentioned as no. 164 in 1640 (see the preceding note) must have been painted after the death of Isabella Brant in June 1626. According to Held 1980, i, p. 345, that entry referred to DPG43, but it could have been any of the many copies or variations after the picture in the Prado, mentioned by Jaffé 1989 and Robels 1989 (see note 18 below).

3 no. 47; Rubens, Een Kabinet-stukxken, verbeéldende dry Vrouwkens, met eenen Fruyt-horen ende Vruchten (a small Cabinet piece, depicting three young women with a cornucopia and fruit); on panel, h 12 in., w 9 in.; sold for 100 [currency of the Austrian Netherlands]. NB: according to Lugt online the lot number was 47, whereas in Terwesten 1770 it was 11. See also note 5 below.

4 GPID (3 June 2014): ‘Rubens; Ceres and Pomona. This excellent Picture is painted in Rubens’s best manner, the composition is grand, the design unusually graceful, and correct – and the colouring pure, rich, and splendid; it is truly, a noble and beautiful production.’ Sold or bt in, £514.10. The price and the characterizations (grand composition, graceful and correct design, noble) indicate that the picture was probably not DPG43.

5 In the sale of J. P. Snyers, 23 May 1758, Antwerp, no. 11: Een Kabinetstukje, verbeeldende drie Vrouwtjes met een Fruit-horen en Vrugten, op paneel, door denzelven [= Rubens]; hoog 12, breet 9 duimen. 100–0–0’. (A small cabinet piece, depicting three young women with a cornucopia and fruit, on panel, by the same [= Rubens]; 12 x 9 in.; ƒ100). See note 3 above for the different lot numbers.

6 ‘SIR P.P. RUBENS. Female Figures, with Garland of Flowers and Fruit, twining their lovely figures in all the splendour and beauty of colouring; the whole is a perfect garland of exquisite colours and beauteous forms.’

7 ‘The Goddess Pomona. – A study of three small figures with fruit. Engraved, I think, by Van Kessel.’ See Related works, no. 1c.

8 Deux nymphes nues, par trop flamandes; l’une cueillant des fruits que l’autre met dans une corbeille. (Two naked nymphs, too Flemish; one picking fruit which the other puts in a basket.)

9 ‘A similar subject is engraved by Van Kessel’. See Related works, no. 1c.

10 ‘The sketch of [Related Works, no. 1a] without the animals and with some changes in the figures is at Dulwich Gallery.’

11 ‘Our plates’ on p. 410: ‘This dashing study […] is one of the most attractive works by Rubens in what Mr. F. Gordon Roe has styled “London’s Forgotten Gallery.”’ The fig. on p. 377 really belongs to Roe 1932.

12 Die Abweichungen zu der Skizze von Rubens in der Dulwich Picture Gallery sprechen dafür, dass Rubens die Anordnung und Ausführung der Tiere und Früchte dem Spezialisten überliess. (The differences from the sketch by Rubens in the Dulwich Picture Gallery suggest that Rubens left the arrangement and presentation of the animals and fruit to the specialist.)

13 However they misread Held 1980: according to Held DPG43 was still in Rubens’s house in 1640, but the authors think he refers to a large composition, like Related works, no. 1b or 1d. See also note 63 below.

14 London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 44 (L. Burchard): ‘A sketch, painted c. 1625–8, for the painting in the Prado […] which, however, shows some variations. Oldenbourg’s dating of the Prado picture, c. 1615–18 [sic; Oldenbourg says c. 1615–17] […] is not convincing and would not agree with the Dulwich sketch.’

15 RKD, no. 49995: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/49995 (May 18, 2014); https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/ceres-y-dos-ninfas/ (July 14, 2019); Büttner 2018a, pp. 120–31, no. 8, where 20 painted copies, 4 drawn and 1 reproduction print (Related works, no. 1c; Fig.) are mentioned, none of which however was made after the painting now in the Prado, but after his copy no. 1, which has disappeared; he suggests that Paul de Vos (1595–1678) was responsible for the monkey in the Prado picture (pp. 125, 129 (note 39)); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 194, fig. 20, under DPG43; Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 123–4, no. 28 (C. Van Mulders: Rubens & Snijders; Nymphs with a Cornucopia); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 1094–5, no. 1664 (Rubens and Snijders; Ceres and two Nymphs); Robels 1989, pp. 374–5, no. 280 (Rubens & Snijders); Jaffé 1989, p. 231, no. 441 (Rubens); Hairs 1977, p. 15 (c. 1611–13; the role of Snijders in this picture remains unclear here).

16 RKD, no. 115770: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/115770 (May 18, 2014); Büttner 2018a, p. 122, under no. 8 (the picture in the Prado), copy no. 7; Jaffé 1989, p. 231, no. 441, copy 2, with further provenance.

17 RKD, no. 298394: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/298394 (Aug. 22, 2020); see also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.131076. For another copy in the BM see https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_R-4-80 (Aug. 2, 2020). According to the BM website (21 Aug. 2020) Pomona and Ceres are depicted here. Büttner 2018a, i, p. 124, under no. 8 (the picture in the Prado); according to Büttner all painted and drawn copies, and this engraving, are made after his copy no. 1, now lost.

18 Willoch 1973, pp. 176–8, no. 420 (Rubens); letter from Françoise Hanssen-Bauer (restorer, Nasjonalgalleriet Oslo) to DPG, 16 March 1995 (DPG43 file). Robels 1989, p. 375, copy no. b; on pp. 375–6 she mentions nine other copies.

19 RKD, no. 295132: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295132 (Aug. 27, 2019); Büttner 2018a, p. 123, copy no. 21 of the Prado picture (as ‘Drawing showing only the right [sic], whereabouts unknown; techniques and mearurements unknown. Prov.: gallery of Gustav Nebehay (1881–1935), Berlin, 1930’; see also Der Kunstwanderer 10 (1928), p. 526, repr.). Robels 1989, p. 375, refers to a photograph: Foto Netherl. Inst. L no. 3689; Erik Löffler of the RKD found it, but it says Ikonogr. Klapper 3689. There is no more information. The same reproduction is in the Rubenium (RUB LB no. 785, under veränderte Ableitungen (changed derivatives), which shows more information: at the time (1930) the drawing was in the possession of Gustav Nebehay, Berlin W 35, Schöneberger Ufer 37).

20 Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 351, as part of the collection of the Duke of Buckingham. Smith adds: ‘N.B. – Sir James Thornhill bought this picture at Paris, which was sold after his death, see pp. 31, 137 [3 Graces in Escurial], and 150 [3 Graces in Florence Gallery].’

21 RKD, no. 292950: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292950 (July 14, 2019); Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 121–2, under no. 8, copy no. 6, with lit.; Bartoschek & Vogtherr 2004, i, p. 427, no. GK I 7592.

22 RKD, no. 295130: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295130 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also http://collection.smk.dk/#/detail/KKSgb7889 (July 14, 2019). Büttner 2018a, i, p. 123, under no. 8 (the picture in the Prado), copy no. 22, ii, fig. 57; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 194, under DPG43; see also Held 1980, i, p. 344, under no. 255.

23 Formerly attributed to Jacques Jordaens, but now attributed to Frans Snijders, as this bird occurs in almost exactly the same pose in two pictures which are known to have had their flora and fauna painted by Snijders (as is assumed for Related works, no. 1a, and a picture by Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert and Frans Snijders, Putti with a Basket of Fruit and Parrots in a Landscape, Christie’s, 12 Oct. 1979, lot 70): see Meij in Meij & De Haan 2001, p. 188, under no. 49 (note 5). Meij assumes that the drawing with a parrot and a monkey in Copenhagen is also by Snijders as studies (see Related works, no. 2bII; Fig.); however Kockelberg & Huvenne (1993, p. 183, no. 88) attribute that drawing to Willem Panneels, seeing it as a copy of animals in different Rubens pictures (see the following note). Robels (1989, p. 159, no. AZ133 (under Studies related to Rubens)) is not quite sure about the Rotterdam drawing: Zwischen Rubens und Snyders strittig […] Für Snyders ungewohnlich ist die farbige Technik mit Gebrauch von Ölkreiden und Wasserfarbe, und obwohl das Stilleben auf dem Gemälde der Erfindung von Snyders zugeschrieben wird, ist zu fragen, ob die schöne Zeichnung nicht ein recordo der Rubenswerkstatt ist? (Disputed between Rubens and Snijders […] For Snijders it is not usual to use coloured oil pastels and watercolours, and although the composition of the still life in the [Prado] picture is attributed to Snijders, one must wonder whether this beautiful drawing is not a recordo from the Rubens studio?); she says something similar on p. 513. Robels 1989, pp. 512–13, no. AZ 133, p. 513: Die Abweichungen zu der Skizze von Rubens in der Dulwich Picture Gallery sprechen dafür, dass Rubens die Anordnung und Ausführung der Tiere und Früchte dem Spezialisten überliess. […] Die Technik ist für Snyders ungewöhnlich, so dass ich es offen lassen möchte, ob die Skizze von seiner Hand stammt oder (eher) ein recordo der Rubenswerkstatt ist. (The differences from the sketch in DPG suggest that Rubens left the arrangement and execution of animals and fruit to the specialist […] The technique is unusual for Snijders, so that I would like to leave it open whether the sketch is by Snijders or (more likely) a ricordo made in the Rubens studio.)

24 RKD, no. 295131: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295131 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also http://collection.smk.dk/#/en/detail/KKSgb7939 (July 13, 2019); on this website the drawing is attributed to Frans Snijders, as it is seen as a preparatory study (?); however Kockelbergh & Huvenne (1993, pp. 181–3 (fig. 88)) attribute it to Willem Panneels, the maker of many of the Cantoor drawings in Copenhagen. They also disagree on the date (before 1628 or before 1650) and on the number of parrots depicted: according to Kockelberg & Huvenne (1993, p. 183, no. 88) there is one parrot, seen from different sides; according to the website of the Copenhagen museum there is more than one parrot.

25 http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/d8488ed8.html (July 14, 2014).

26 RKD, no. 22290: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22290 (July 14, 2019); Ost 2008; Kockelbergh & Huvenne 1993, pp. 180–83; Jaffé 1989, p. 305, no. 913 (before 1620 and before 1628); Vandamme 1988, p. 323, no. 312.

27 RKD, no. 295133: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295133 (Aug. 31, 2019); Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 126, 129 (note 47), ii, fig. 53; Bober & Rubinstein 1986, p. 133, no. 101, figs 101 and 101a; Van der Meulen 1994–5, i (1994), p. 59; Kieser 1933, p. 119, fig. 8. See for the 16th-century print after the sculpture mentioned in Bober & Rubinstein, p. 133, RKD, no. 295134: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295134 (Aug. 31, 2019), published in De Cavalleriis 1593 and 1594, fig. 53.

28 https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/a-satyr-pressing-grapes-with-a-tiger-and-leopard-142669/search/actor:rubens-peter-paul-15771640/page/6 (July 14, 2019); https://www.ashmoleanprints.com/image/410888/sir-peter-paul-rubens-a-satyr-pressing-grapes-with-a-tiger-and-leopard (July 14, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 98–9, no. 17; Casley, Harrison & Whiteley 2004, p. 195, no. A153; White 1999a, pp. 104–6, no. A 153, pl. 11; Jaffé 1989, pp. 240–41, no. 496 (c. 1618); Cleaver, White & Wood 1988, p. 86, no. 23; Held 1980, i, pp. 353–4, no. 263, ii, pl. 275. In these publications (with the exception of Lammertse & Vergara 2018) the relation with the picture in the Prado (Related works, no. 1a) is not mentioned, nor is the modello for its pair, DPG43.

29 Robels 1989, pp. 128, 375; Bottineau 1958, pp. 35, 44, no. 80; Orso 1986, p. 102 and fig. 37; on p. 57 Orso refers to Held 1980 pp. 344–5, 353–4 and 191, nos 27–8; Volk 1980a, p. 180 (from the inventory of 1636): Otros dos lienços yguales de tamaño como los dhos y mas angostos, de la misma mano y molduras que el vno es un satiro que esta exporimiendo un racimo de obas a dos chiquellos y vna tigre recien parida con tres cachorrillos – el otro es la Diosa Ceres con otras dos ninphas que tienen una cornicopia de frutas y un mico a los pies que esta comiendo otras frutas. (Translation in Orso 1986, p. 191 [27–8]: Two other canvases of equal size, of the same size as and narrower than the preceding ones [a picture of Samson and one of David], with the same hand and frames. One is a satyr who is squeezing out a bunch of grapes to two small children. There is a tiger just delivered of three small cubs. The other is the goddess Ceres with two nymphs who holds a cornucopia of fruits. There is a monkey at their feet that is eating other fruits.) Sutton (in Sutton & Wieseman 2004, p. 182) incorrectly states that Rubens’s picture of Ceres in this inventory included a satyr and a tiger, conflating the two pictures. For the decoration of the Alcázar in general see Orso 1986 and Checa 1994. For a drawing after the young satyr on the right in Rubens’s Cantoor in Copenhagen see Held 1991, pp. 425 (fig. 18), 426, under no. 157 (V, 11). There Held contradicts the identification by Garff & De la Fuente Pedersen (1988, i, pp. 126–7, no. 157) as Bacchus (after Van Dyck).

30 Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 195, fig. 21, under DPG43; Marx 2005–6, ii (2006), p. 456, no. 1578 (Gal. no. 974; c. 1618–20); White 1999a, pp. 104–6, under no. A153 (Related works, no. 3a); Held 1980, i, pp. 353–4, under no. 263 (Related works, no. 3a); Evers 1943, pp. 227–8, fig. 229; Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), under no. 610.

31 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/titian-diana-and-actaeon (July 14, 2019); Humfrey 2007, pp. 290–91, no. 221. For the poesie for Philip II see Wethey 1969–75, iii (1975), pp. 71–84, for Rubens’s copies painted in Spain (1628–9) Wood 2010a, pp. 43–8, and for those painted in London (1629–30), ibid., pp. 49–50.

32 RKD, no. 295135: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295135 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=9 (July 14, 2019); Wood 2010b, pp. 186–90, no. 12, fig. 69, purchased at Christie’s, 9 Dec. 1982, lot no. 78; Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 76–8, no. 7; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 397–400, no. 101; Wood 2002, p. 26, fig. 14; Volk 1981, pp. 520, 522 (fig. 18); Jaffé 1977, p. 33R, pl. XVI (1628).

33 RKD, no. 50031: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/50031 (Aug. 25, 2019); see also http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/437525?rpp=30&pg=1&ft=rubens%2c+peter+paul&pos=8 (July 14, 2019); Woollett & Van Suchtelen 2006, pp. 60–63, no. 3 (c. 1614–15); Schoon & Paarlberg 2000, pp. 288–9, 370, no. 66 (M. van Soest); Jaffé 1989, p. 202, no. 286 (1614–15). This picture is depicted (as is Related works, no. 12f under DPG451, see note 49 under DPG451) in the painting by Jan Brueghel II, An Allegory on the Art of Painting, c. 1625, oil on copper, 47 x 75 cm. Private collection, The Netherlands: see E. Hermens in Komanecky & Bowron 1999, pp. 158–61, no. 9.

34 http://art.seattleartmuseum.org/objects/23798/the-origin-of-the-cornucopia?ctx=805e1d88-935e-4c39-98ab-60a02876865c&idx=0 (as The Origin of the Cornucopia, July 14, 2019); J. Vander Auwera in Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 171 (fig. 75), 191, under no. 63.

35 RKD, no. 70546: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/70546 (July 14, 2019); see also http://www.fine-arts-museum.be/nl/de-collectie/abraham-janssen-van-nuyssen-de-naiaden-vullen-de-hoorn-des-overvloeds?letter=j&page=1 (July 14, 2019).

36 RKD, no. 274915: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/274915 (Aug. 25, 2019); see also http://collection.smk.dk/#/en/detail/KMSsp233 (July 14, 2019); see Vander Auwera 2012, pp. 166 (fig. 70), 168, 191 (note 13), where its possible pair, now in Dresden, is also mentioned.

37 RKD, no. 57719: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/57719 (July 14, 2019; Rubens); Vlieghe 2013, p. 59 (Rubens); Bellini & Gritsay 2007, pp. 77–83 (Rubens and Snijders); Gritsay & Babina 2008, pp. 230–33, no. 300 (N. Gritsay: Rubens and Snijders); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), p. 80, under no. 61, iii (1995), fig. 117; Jaffé 1989, p. 193, no. 240 (Rubens).

38 RKD, no. 225093: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/225093 (July 14, 2019; Rubens and studio); Vlieghe 2013, p. 59 (copy, ‘which may not even have been executed in Rubens’s studio’); J. vander Auwera in Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 180–81, no. 68 (Rubens; Snijders is not mentioned); Bellini & Gritsay 2007, pp. 85–93 (Rubens and Snijders).

39 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1850-1214-49 (Aug. 2, 2020); I. Schaudies in Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 184–5, no. 70.

40 https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/ofrenda-a-ceres/ (Dec. 21, 2020); Díaz Padrón 1996, i, pp. 624–5, no. 1547; Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 182–3, 191 (J. Vander Auwera: c. 1624–5).

41 RKD, no. 295155: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295155 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1859-0611-160 (Aug. 2, 2020).

42 https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/diana-y-calisto/ (July 14, 2019); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 926–9, no. 1671; Jaffé 1989, p. 367, no. 1352 (1637–8).

43 RKD, no. 184563: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/184563 (July 14, 2019); C. van Mulders in Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 115–16, no. 24; McGrath 2006 (not the Three Graces); Woollett & Van Suchtelen 2006, p. 160 (fig. 83); Bodart 1990, pp. 128–9, no. 44; Jaffé 1989, p. 209, no. 322. This picture was in the collection of the Duke of Buckingham (1625–7) and the Amsterdam collector Gerrit Braamcamp (sale 1771).

44 https://www.accademiasanluca.eu/it/collezioni_online/pittura/archive/cat_id/1788/id/604/l-abbondanza-coronata-dalle-ninfe (July 16, 2019); Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 456–7, no. R1 (under ‘Questionable and Rejected Attributions’), ii, fig. 308, with as dimensions 48.5 × 34.5 cm; Díaz Padrón & Padrón Mérida 1999, pp. 108–9, no. 18; Jaffé 1989, p. 270, no. 696; Held 1980, i, pp. 350–51, no. 260, ii, pl. 250.

45 RKD, no. 108602: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/108602 (Aug. 26, 2019); see also http://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/1853 (July 14, 2019); Roe 2006, p. 154, no. 267; Jaffé 1989, p. 206, no. 303 (c. 1615); Held 1980, i, pp. 325–6, no. 238, ii, pl. 242.

46 RKD, no. 57718: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/57718 (July 16, 2019); Gritsay & Babina 2008, pp. 240–44, no. 305 (note by N. Gritsay; Rubens and Snijders); Jaffé 1989, p. 206, no. 304.

47 Vander Auwera in Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, p. 171 (fig. 74), under no. 63; Meij & De Haan 2001, pp. 101–2, under no. 15. Fig. 1 on p. 102 shows a 19th-century print (in reverse) after this picture; Evers 1943, p. 237, fig. 240.

48 RKD, no. 7343: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/7343 (July 14, 2019); see also https://www.mauritshuis.nl/nl-nl/verdiep/de-collectie/kunstwerken/nimfen-vullen-de-hoorn-des-overvloeds-234/detailgegevens/ (Aug. 26, 2019); A. van Suchtelen in Woollett & Van Suchtelen 2006, pp. 122–7, no. 13 (Jan Brueghel I and Workshop of Peter Paul Rubens; 109.5 x 165.7 cm); Logan & Plomp 2004c, p. 136, under no. 32.

49 https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/ninfas-y-satiros/ (July 14, 2019); De Clippel 2007; Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 960–61, no. 1666; Jaffé 1989, p. 366, no. 1347; Evers 1943, p. 237, fig. 242.

50 Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 90–91, no. 14; Joconde (26 May 2014); Foucart & Foucart-Walter 2009, p. 242, no. M.I. 967; see also Woollett 2006, pp. 25–6, 39–40 (fig. 27); Wieseman 2004, p. 63 (fig. 16); Vlieghe 2000, p. 202 (fig. 6); Jaffé 1989, pp. 170–71, no. 118.

51 Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 90–91, under no. 14, fig. 44; see also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/filopomenes-descubierto/ (May 26, 2014); see also Woollett 2006, pp. 25–6, 39–40 (fig. 26); Jaffé & McGrath 2005, pp. 190–91, no. 89 (c. 1612–13); Vlieghe 2000, p. 201 (fig. 5); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 1102–3; Jaffé 1989, p. 171, no. 119.

52 According to Vergara (1999, p. 46) they were not a gift, as has often been assumed.

53 The three other pairs comprised scenes from the Old Testament, Roman history and Roman mythology. On the eight pictures in the Hall of Mirrors in general: Orso 1986, pp. 56–117; on p. 83 is a table with the dimensions of the pictures in 1686. The other six subjects were The Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau, Gaius Mucius Scaevola before Porsenna, Samson breaking the Jaws of a Lion, David strangling a Bear, The Calydonian Bear Hunt, and Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer. See also Vergara 1999, p. 46–7; Orso 1993, pp. 89–91 (fig. 48, pl. 7).

54 For later entries in Spanish archives see Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, p. 1094.

55 Vergara 1999, p. 48.

56 Vergara (1999, p. 51) refers to documentation (letters by Isabella and the King) in Gachard 1877, pp. 183–4.

57 Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), p. 132; Oldenbourg 1921, pp. 126, 459; L. Burchard in London/Leeds 1947–53, no. 44 (see note 14 above); Held 1980, i, pp. 344–5; Jaffé 1989, p. 230, no. 440.

58 Perhaps that was done for marketing reasons: Rubens was of course more famous than Snijders. However Snijders was by then a master in his own right.

59 The Prado picture is not mentioned in the book about Snijders by Koslow 1995a and 1995b.

60 Robels 1989, p. 128.

61 Email from Alejandro Vergara to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 3 June 2014 (DPG43 file), for which many thanks.

62 See the preceding note. Büttner 2018a, i, no. 8, suggests Paul de Vos for the monkey (see note 15 above).

63 Kockelberg & Huvenne 1993 misread Held and think that he meant another full-scale composition by Rubens, which Panneels could have copied before 1630, when he left Rubens’s studio. Copies of the Prado picture still exist after which Panneels could have worked (e.g. Related works, nos 1b and 1d), but Held associated the 1640 source with DPG43 and not with Related works, no. 1b, or with any other of the copies mentioned by Jaffé 1989 and Robels 1989 (see note 18 above). According to Büttner 2018a, all the other copies were made after his copy no. 1, now lost (see note 15 above).

64 Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 124–6, ii, fig. 50; his copy no. 1 of his cat. no. 8 is on p. 121; his cat. no. 9 (presumably lost) is on p. 133.

65 Robels 1989, p. 375: Eine Nachzeichnung im Museo del Prado (Foto Netherl. Inst. L no. 3689) zeigt schon die veränderte Haltung der linken und mittleren Najade, während die rechte hier aus dem Bilde herausschaut und Blumen in ihrer Rechten hält. Möglicherweise handelt es sich um eine Kopie einer verlorenen weiteren Skizze zu der endgültigen Fassung. Das Stilleben auf dem Bodem ist auf der Nachzeichnung ausgespart. (A drawn copy in the Prado [sic; the present whereabouts of this drawing are unknown] already shows the changed posture of the left and central nymph, while the right one looks out of the image and has flowers in her right hand. Possibly this is a copy of another, lost, sketch for the definitive composition. The still life on the ground is left out on the copy.) In addition, the woman on the right in this drawing does not look like the one in DPG43 or in the Prado picture. See also note 19 above.

66 Her pose looks like that of the nymph to the right of the cornucopia in the Achelous scene in New York (Related works, no. 4c.I; Fig.), but her hands are depicted differently.

67 Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, p. 124 (note 1); Held 1980, i, p. 344 (Met. IX.87–88).

68 It seems that parrots are not mentioned by Ovid, so that must be an invention by Jan Brueghel I (or Rubens?). The Feast of Achelous is characterized as ‘an open air collector’s cabinet’ by M. van Soest in Schoon & Paarlberg 2000, p. 288. We encounter parrots in 17th-century paintings depicting treasures from the East, such as the picture by Jacob van Campen in the Oranjezaal, Part of the Triumphal Procession, with Presents from the East and the West (see Van Eikema Hommes & Kolfin 2013, p. 145 (fig. XXIV)) or in still lifes with black pages and Chinese porcelain, again symbols of Oriental richness. However in a painting by Frans Francken II (formerly called The Kunstkammer of Sebastian Leerse, c. 1628–9, KMSKA, Antwerp, 669) the parrots are supposed to symbolize human folly, reproaching those who are not concerned with arts and science. They are considered to be jammers, which are noisy and cause a lot of dust and dirt: see Van de Velde 2014, p. 25, no. 37. This seems to be too modern an interpretation.

69 Bober & Rubinstein 1986, p. 201, no. 169, figs 169 and 169a: Sacrifice with a Victory, fragment of a Trajanic? relief, Louvre, Paris, MA 392. The figure on the left with the cornucopia is supposed to be Abundantia or Fortuna. See also ibid., pp. 229–30, no. 196, figs 196 and 196a: Roman sarcophagus, AD 164–82, Marriage ceremony, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Rome. The figure on the left wearing a turreted headdress and carrying a cornucopia represents the Tyche (Fortuna) of a city or province.

70 J. Vander Auwera in Van der Auwera & Schaudies 2012, p. 181 (fig. 84); according to Van der Meulen (1994–5, ii (1994), p. 80) Rubens’s statue differs slightly from the one in the Borghese collection; see also ibid., ii (1994), pp. 79–82, nos 61–2, iii (1995), figs 114–19.

71 She is often found with Bacchus, the god of wine, and Venus (Sine Cerere and Baccho friget Venus; see DPG165); she may also personify Earth (in a series of Elements) or Summer (in a series of Seasons). In Dulwich there is another scene from the story of Ceres, with the boy Stellio who mocks her: The Mocking of Ceres (DPG191, Godefridus Schalcken (?), after Adam Elsheimer; see RKD, no. 297781: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/287781 (July 14, 2019).

72 The title of the print by Theodor van Kessel (Related works, no. 1c).