Peter Paul Rubens DPG19

DPG19 – Romulus Setting Up a Trophy

1625; [paper? on] oak panel, 49.6 x 15.6 cm

For the pieces of wood see [1];1 before restoration, c. 1945, width c. 32.1 cm2

PROVENANCE

?Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741), Venice, 1740;3 ?Angela Carriera (Pellegrini’s widow), Venice, 1741; sold to Joseph Smith, British Consul in Venice, before 1762: his inventory, 1762 (original lost, copy of c. 1815 in Lord Chamberlain’s Office (Flemish and Dutch painting, no. 39: ‘A Soldier, Mars [or Man?] with Military Trophy [on] board 1'7½" x 1'2½"’ (c. 49.5 x 37 cm);4 bt King George III of England, 1762; ?Desenfans sale, 16 Jun. 1794 (Lugt 5226), lot 177 (‘Rubens – Eneas contemplating the armour of Achilles’; 1'10" x 2'3" (c. 56 x 68.5 cm));5 Insurance 1804, no. 26 (‘Achilles contemplating armour – Rubens; £60’); Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 1, no. 1 (‘Small parlour, no. 1; Sketch: full length figure of a Man in Armour: Pan[el]; Rubens’; 2'4" x ‘2f’).

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 9, no. 163 (‘SECOND ROOM – East side; A Sketch of a Man carrying Armour; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 386, no. 163;6 Cat. 1820, p. 9, no. 163 (Sketch of a Man carrying Armour); Cat. 1830, no 174; Jameson 1842, ii, p. 470, no. 174 (‘A Sketch’); Denning 1858, no. 174;7 Denning 1859, no. 174; Sparkes 1876, p. 151, no. 174 (Rubens; ‘A Sketch’); Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 145, no. 174 (painted in the style of Rubens by his scholars or imitators; A Roman soldier with a trophy); Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 5, no. 19 (School of Rubens); Cook 1914, p. 14; Cook 1926, p. 13; Grossmann 1948, pp. 47 (fig. 33; 1622–5; 49 x 15 cm), 52; Cat. 1953, p. 35, no. 19 (Rubens, Aeneas with the spoils of Mezentius); Blunt & Croft-Murray 1957, p. 20 (note 14); Vivian 1962, p. 332 (note 32); Vivian 1971, p. 203, no. 39, fig. 69; Murray 1980a, p. 111, no. 19 (Rubens, Aeneas with the Arms of Mezentius); Murray 1980b, p. 24, no. 19; Held 1980, i, pp. 375–6, no. 279 (Romulus carrying the Trophy of Acron, c. 1625–7), ii, pl. 279; Logan 1981, p. 517 (Aeneas); Held 1981, pp. 62–3, fig. 60 (Romulus); Jaffé 1982, p. 64; Editorial 1983; Held 1983a, pp. 134, 139 (fig. 9); Jaffé 1983a, p. 139 (fig. 9) and pp. 147–8; Delmarcel 1983; Bodart 1985, p. 182, no. 604 (Enea con le armi di Mezenzio); Cleaver 1986, pp. 48–50 and fig. 5; Jaffé & Cannon-Brookes 1986, p. 784; Jaffé 1989, p. 373, no. 1390 (1635–9); Bodart 1990, p. 136, under no. 48 (Related works, no. 3); De Poorter in De Poorter, Jansen & Giltaij 1990, pp. 92–5, under no. 25 (Related works, no. 2b); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 89, ii, pp. 114–16, 118, 122–5, 134–5, 141, 143, 151–4, no. 30, pp. 156, 159, 160; Beresford 1998, p. 206 (Romulus setting up a Trophy); Borean 2009, pp. 23, 44 (note 140), fig. 16; p. 82 (fig. II); Galen 2012, pp. 388–9, under A 38 (uncertain and rejected pictures by Jan Boeckhorst; Related works, no. 4b; Fig.); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 191–3, 213; RKD, no. 274710: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/274710 (July 13, 2019).

EXHIBITIONS

London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 42 (L. Burchard: Rubens; Aeneas with the Spoils of Mezentius; c. 1622–5; design for a tapestry); Madrid/Bilbao 1999, pp. 108–9, no. 21 (I. Dejardin); London 1999b (no cat. no.), c. 1625–7; Lille 2004, p. 302, no. 163 (H. Vlieghe; heavily overpainted, 1630s, made for tapestries; the cartoons in Cardiff are made by Jan Boeckhorst 1640–50).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Three-member oak panel joined horizontally, with a horizontal grain. The ground is white, with some grey underpaint visible beneath flesh areas and the crimson cloak. The original panel has been set into a shallow wooden support tray. There is an old repaired horizontal split and old paint losses along the panel joins and the split. The craquelure follows the wood grain and is slightly raised in some places. Wear and abrasion has occurred, much of which has been retouched. An X-radiograph reveals white paint between his legs that could have been fluttering drapery [1]. Some overpaint remains in the lower part of the painting beneath his feet and in the dark background; the red of the drapery looks to have been strengthened. Previous recorded treatment: 1922, repaired, Reeve; 1922, varnished and frame glazed; c. 1946, reframed, Pollack; 1985, examined, National Maritime Museum, E. Hamilton-Eddy.

RELATED WORKS

Romulus series

1) (sketch) Peter Paul Rubens, Romulus setting up a Trophy, oil on paper, mounted on wood, 35.2 x 21.6 cm (13 x 8 pouces). Present whereabouts unknown (A.-F. Poisson de Vandières, marquis de Marigny et de Menars, sale, 25 March 1782, Paris, Basan-Jouillain (Lugt 3376 and 3389), lot 99b (deux belles esquisses, savamment touchées […] un guerrier formant un faisceau d’armes sur le tronc d’un gros arbre (two beautiful sketches, cleverly fabricated […] a warrior forming a bundle of arms on the trunk of a large tree); sold De Joubert; 145 livres 19.8

2a) Peter Paul Rubens, The Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1630–34, panel, 44.3 x 32.3 cm. Israel Museum, Jerusalem, B86.0910 [2].9

2b) attributed to Peter Paul Rubens, The Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1630–34, panel, 40.3 x 35.5 cm. BvB, Rotterdam, 2300 (on loan from the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, NK 2675) [3].10

3) Peter Paul Rubens, Romulus appearing to Julius Proculus, c. 1630–34, panel, 44.2 x 32.5 cm. Octave Mareels collection, Aalst, Belgium [4].11

4a.I) Tapestry cartoon: Follower of Rubens, Jan Boeckhorst (?), Romulus killing Remus, tempera on paper, 276.4 x 206 cm. National Museum Cardiff , NMW A 227 [5].12

4a.II) Romulus killing Remus, tapestry, 333 x 254 cm. Private collection, Rome.13

4b) Tapestry cartoon: Follower of Rubens, Jan Boeckhorst (?), Romulus erecting a Trophy on the Capitol, tempera on paper, 282.8 x 189.5 cm. National Museum Cardiff, NMW A 230 [6].14

4c) Tapestry cartoon: Follower of Rubens, Jan Boeckhorst (?), The Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, tempera on paper, 278.3 x 207.7 cm. National Museum Cardiff, NMW A 228 [7].15

4d.I) Tapestry cartoon: Follower of Rubens, Jan Boeckhorst (?), Romulus appearing to Proculus, tempera on paper, 280.2 x 189.5 cm. National Museum Cardiff, NMW A 229 [8].16

4d.II) Romulus appearing to Proculus, tapestry, 330 x 224 cm. National Museum Cardiff.17

4e) Jan Boeckhorst, The Snijders Triptych, c. 1659, panel, shutters each 107.63 x 48.26 cm, middle panel 107.63 x 86.36 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation, M.2008.90a–c.18

5a) Modello for 5b: Peter Paul Rubens, Mars and Rhea Silvia, c. 1616–17, canvas (originally on panel), 46.4 x 65.6 cm. Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, GE 115.19

5b) Peter Paul Rubens, Mars and Rhea Silvia, c. 1616–17, canvas, 209 x 272 cm. Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, GE 122.20

6a) Tapestry cartoon: Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert or Jan Boeckhorst (?), Two Romulus subjects, gouache on paper glued to two pieces of canvas, 303.5 x 274.3. John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Fla., SN 222a and b.21

6b) Tapestry cartoon: Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert or Jan Boeckhorst (?), The Death of Turnus and another subject, gouache on paper glued to two pieces of canvas, 302.9 x 142.2 cm (a), 303.5 x 139.7 cm (b). John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Fla., SN 223a and b.22

Other men in armour by Rubens

7) Peter Paul Rubens, Miles Christianus / Study of a Roman Hero or Martyr holding a Lance, possibly Longinus (previously St Maurice), c. 1614–16, panel, 36.2 x 13.8 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, 9 July 2008, lot 20; Neuerburg collection) [9].23

8a) Modello for 8b: Peter Paul Rubens, Decius Mus relating his Dream (or Addressing the Legions), probably 1616, hardboard (originally painted on wood panel), 80.7 x 84.7 cm. NGA, Washington, 1394, Samuel H. Kress Collection 1957.14.2.24

8b) Peter Paul Rubens, Decius Mus relating his Dream, c. 1616–17, canvas, 294 x 278 cm. Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, GE 47.25

8c) Peter Paul Rubens and studio, A Trophy, 1618, canvas, 289 x 126 cm. Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, GE 53.26

9) Peter Paul Rubens, The Birth of Henri IV, 1628, panel, 21.2 x 9.9 cm. The Wallace Collection, London, P523.27

10) Peter Paul Rubens, The Trophy raised to Constantine, c. 1622–3, panel, 37 x 29.4 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Saul P. Steinberg collection).28

11) Peter Paul Rubens, The Vision of Aeneas, 1630s, panel, 47 x 32 cm. National Museum Cardiff, NMW A 34.29

Men in armour by other artists

12a) Guido Reni, Vision of St Maurice, c. 1619, canvas, 242 x 143 cm. Santa Maria dei Laghi, Avigliana.30

12b.I) Agostino (and Annibale?) Carracci, Romulus dedicates to Jupiter Feretrius the Trophies of the defeated King Acron (part of Romulus and Remus, History of Rome series), fresco. Palazzo Magnani, Bologna.31

12b.II) Print after 12b.I: Louis de Châtillon after Annibale Carracci and Carlo Bononi, Romulus dedicates to Jupiter Feretrius the Trophies of the defeated King Acron, 1659, etching and engraving on beige paper, 447 x 440 mm (image). Teylers Museum, Haarlem, KG 14527.32

Antique sources

13a) Antique cameo, Gemma Tiberiana (The Apotheosis of Germanicus), five-layered sardonyx, 31 x 26.5 cm. Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.33

13b) Peter Paul Rubens, Gemma Tiberiana (The Apotheosis of Germanicus), pen and brown ink, washed, heightened with white, 327 x 270 mm. Stedelijk Prentenkabinet, Antwerp, 109.34

13c) Peter Paul Rubens, The ‘Apotheosis of Germanicus’: copy after an Antique cameo (the ‘Gemma Tiberiana’), canvas, 100 x 82.6 cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 3522.35

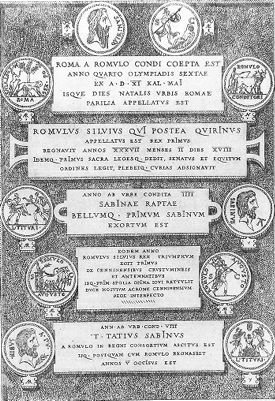

13d) Engraving of Antique coins illustrating the history of Romulus, from Hubert Goltzius, Fastos Magistratuum, Bruges 1566 (also in Hubert Goltzius, Opera, Antwerp 1645, i, pl. 1) [10].36

Burgonets

14a.I) Burgonet of the Emperor Charles V, Augsburg, c. 1530, embossed, etched, chased, and gold-damascened steel, fabric and leather, h 19 cm, w 25 cm, d 34 cm, weight 1,705 gr. Real Armeria, Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid, A.59.37

14a.II) Circle of Filippo Negroli (c. 1510–79), Parade Burgonet, low-, medium-carbon steel and copper alloy, embossed, weight 1,800 gr. The Wallace Collection, London, A106.38

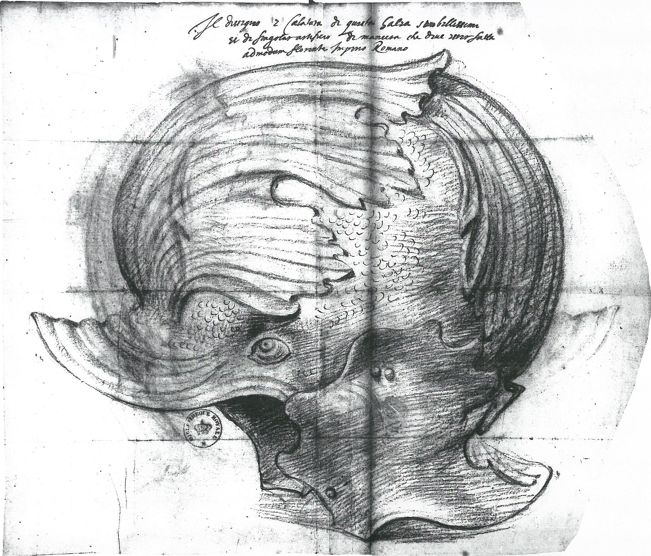

14b.I) Assistant of Rubens ?after Filippo Negroli, retouched by Rubens, A Parade Burgonet in the Shape of a Dolphin, inscribed in Italian, black chalk, retouched in pen and ink, 275 x 300 mm. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, MS Dupuy 667, fol. 159r [11]. 39

14b.II) Michel François Demasso after Rubens after Filippo Negroli, A Parade Burgonet, engraving in Jacob Spon, Miscellanea eruditae antiquitates.40

14c) Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of a Man in Armour, probably as Mars, panel, 82.6 x 66.1 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Rafael Valls 2012, pp. 119–23, no. 51).41

14d.I) Tapestry cartoon: Jacques Jordaens, Bust of a helmeted Warrior, c. 1660, watercolour and black chalk on grey paper, 509 x 470 mm. Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie, Besançon, D.2609.42

14d.II) Matthys Roelants et al. after Jacques Jordaens, Charlemagne, the Conqueror of Italy, presented with a Crown and Keys, tapestry, c. 500 x 300 cm. Prince de Ligne collection, Château d’Antoing.43

Comparable enlargement of a sketch

15a) Sketch for 15b: Peter Paul Rubens, The Rape of Ganymede, c. 1636–40, panel, 33.5 x 24.5 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, 5 Dec. 2007, lot 18).44

15b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Rape of Ganymede, c. 1636–40 (part of the Torre de la Parada series), canvas, 181 x 87 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1679.45

Stylistically comparable sketches

16a) Modello: Peter Paul Rubens, St Teresa intercedes for Souls in Purgatory, c. 1630–33, panel, 44.8 x 37.1 cm. Museum Wuyts van Campen-Baron Caroly, Lier, 41.46

16b) Modello: Peter Paul Rubens, Constantine investing his Son Crispus with Command of the Fleet (318?), 1622, panel, 37.6 x 30 cm. Private collection, Sydney.47

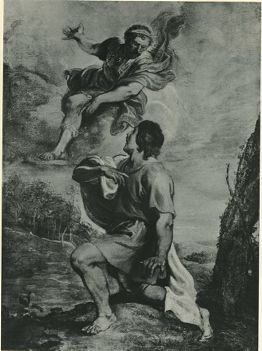

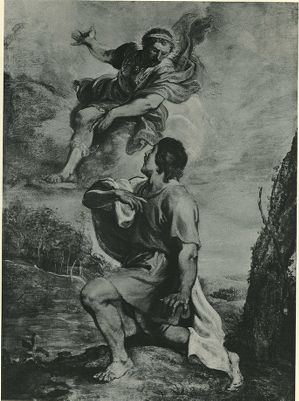

DPG19

Peter Paul Rubens

Romulus setting up a Trophy, c. 1622-1626

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG19

1

X-ray of DPG19

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1630-1634

Jeruzalem (city, Israel), The Israel Museum, inv./cat.nr. B86.0910

3

after Peter Paul Rubens

Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1630-1635

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 2300 (OK)

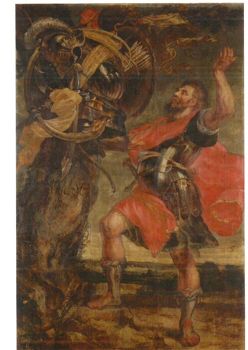

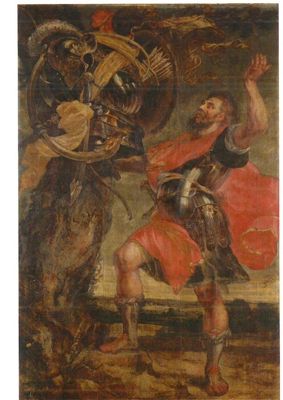

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Romulus appearing to Julius Proculus, c. 1630-1634

Whereabouts unknown

5

after Peter Paul Rubens possibly Jan Boeckhorst

Romulus killing Remus, c. 1635-1650

Cardiff (city, Wales), National Museum Cardiff, inv./cat.nr. NMW A 227

6

after Peter Paul Rubens possibly Jan Boeckhorst

Romulus setting up a Trophy on the Capitol, c. 1635-1650

Cardiff (city, Wales), National Museum Cardiff, inv./cat.nr. NMW A230

7

after Peter Paul Rubens possibly Jan Boeckhorst

Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1635-1650

Cardiff (city, Wales), National Museum Cardiff, inv./cat.nr. NMW A 228

8

after Peter Paul Rubens possibly Jan Boeckhorst

Romulus appearing to Julius Proculus, c. 1635-1650

Cardiff (city, Wales), National Museum Cardiff, inv./cat.nr. NMW A 229

9

Peter Paul Rubens

Roman warrior, c. 1614-1616

New York City, Zürich, art dealer David Koetser

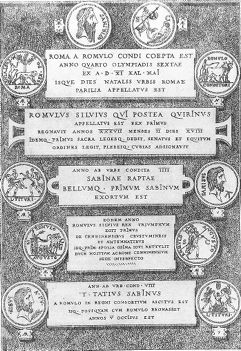

10

Hubert Goltzius

Scenes from the life of Romulus, 1645

Whereabouts unknown

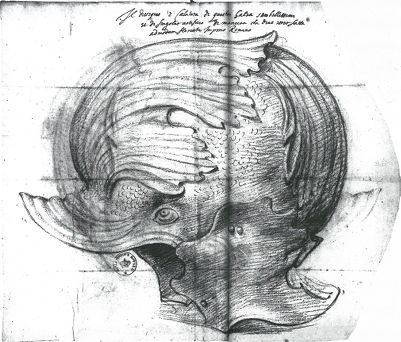

11

studio of Peter Paul Rubens and touched up by Peter Paul Rubens after Filippo Negroli

Parade burgonet in the shape of a dolphin, 1628-1636

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, inv./cat.nr. MS. Dupuy 667, fol. 159r

Denning in 1858 called DPG19 ‘A Study doubtless by Rubens’, but Richter and Sparkes in 1880 said that the painting was after the master. However, after the removal of old lateral additions (for modelli with comparable additions see Related works, no. 7 and 15a) and overpainting in the mid-20th century, Burchard in 1947 accepted it as being by Rubens, and this has been generally agreed ever since. Burchard dated the picture to c. 1622–5, i.e. shortly after Rubens’s completion of tapestry designs on the life of Constantine. He considered the sketch to be a model for a print or a tapestry, since the soldier wears his sword on his right side (it would normally be on the left). The panel’s tall thin shape indicates that it was probably meant for a tapestry, and specifically for a panel to be hung between windows, similar to A Trophy, part of the Decius Mus series (Related works, no. 8c). Michael Jaffé dated the panel to 1635–9, since he assumed that DPG19 was part of a project which was left unfinished at the time of Rubens’s death in 1640. Vlieghe also dated the project, and DPG19, to the 1630s. McGrath considered that DPG19 and the other sketches (see below) were made before 1626, but she thought dating was difficult because of overpainting. However investigation by Sophie Plender on 6 October 2014 showed that the overpainting was minor (see Technical Notes). McGrath suggests that originally the sketch may have been ‘quite thinly painted’ and compares DPG19 with sketches for an altarpiece at Lier, dated by Held 1630–33 (Related works, no. 16a), and one in Sydney, dated 1622 (Related works, no. 16b).48 However these are both rather diverse in time and style.

Held dated the other Romulus scenes (Related works, nos 2a–b and 3) [2-4] in the period 1630–34, whereas he proposed a dating of c. 1625–7 for DPG19. Indeed, stylistically there are considerable differences between the four pictures that are assumed to be a series with scenes from the life of Romulus. According to us, DPG19 could also be compared to the picture of a Roman Hero that was on the London art market in 2008 (formerly Neuerburg collection; Related works, no. 7) [9], generally dated c. 1614–16, which is also considered to be a design for a tapestry. Here we see the same dark background and a similarly detailed depiction of armour as in Related works, nos 2a–b and 3. Moreover the dimensions are about the same as DPG19. It seems that the last word has not been said about the date of DPG19.

The identification of the scene depicted in DPG19 has long been controversial. First it was generically called a ‘Trophy’ or a ‘Soldier’. It was called Altro [quadro] con Trofeo in a posthumous inventory of the possessions of the Venetian painter Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741), if that was indeed DPG19. It is uncertain when or where Pellegrini obtained the panel. However he worked in the Netherlands in 1714 (The Hague), 1716–17 (Antwerp), and 1717–18 (Amsterdam and The Hague).49 After his death Pellegrini’s widow seems to have sold the picture to the English Consul in Venice, Joseph Smith (1674/82–1770), from whom King George III (1738–1820) purchased it in 1762 as ‘A soldier, Mars [or man?] with military trophy on board’; it seems that the picture had already been enlarged.50 It is uncertain when or why the picture left the Royal Collection, but it next appears – probably – as part of the sale of Noel Desenfans’ collection in 1794 as Eneas contemplating the armour of Achilles, and is included in his subsequent 1804 Insurance list as Achilles contemplating armour, before passing to Sir Francis Bourgeois in 1807. The picture is not mentioned in Desenfans’ 1790–91 inventory or any of his other lists or catalogues.

According to Desenfans (in 1794 and 1804) the subject of the picture was Aeneas, but in the 19th- and early 20th-century Dulwich catalogues it became just a man in armour. Burchard (1947) returned to the Aeneas story, when he called the subject of DPG19 Aeneas holding the arms of Mezentius. In 1980, however, Julius Held suggested that the subject of DPG19 was part of the history of Rome, founded by Romulus and Remus: Romulus carrying the trophy of Acron or, more precisely, Romulus erecting a trophy on the Capitol to Jupiter Feretrius from the spoils of Acron.51 And following up a suggestion by Burchard published in 1947, Held said that it was part of a group with three other panels. While Burchard thought they were part of an Aeneas series, Held identified these as two versions of the Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius (Related works, nos 2a–b) [2-3] and Romulus appearing to Julius Proculus (Related works, no. 3) [4].

In 1983 the Burlington Magazine published a series of articles by Michael Jaffé and Julius Held, later joined by Hans Vlieghe and Guy Delmarcel, concerning a series of four tapestry cartoons that had been recently acquired by the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, as by Rubens (Related works, nos 4a–d) [5-8]. DPG19 was used for one of these cartoons (Related works, no. 4b) [6], albeit with some differences: the upright format of DPG19 changed to more of a square format in the Cardiff cartoon; in the Dulwich panel Romulus carries the trophies, whereas they seem to hang awkwardly from a tree in the Cardiff cartoon, which also has more trophies, and the posture of arms and legs and the draperies have become more dramatic in the cartoon compared with the relatively restrained attitude of the man in the Dulwich painting. While Held argued that the cartoons were not by Rubens and that they were part of a Romulus series, Jaffé insisted they were made by Rubens in the 1630s and part of an Aeneas series. Vlieghe suggested that the author of the Cardiff cartoons was Jan Boeckhorst (1604/5–68), who had based his compositions on designs by Rubens.52 Stylistically comparable work by Boeckhorst is dated later, for instance the Snijders triptych now in Los Angeles (c. 1659; Related works, no. 4e) – one of the reasons why the cartoons could not have been by him, according to Jaffé (and McGrath).53 Galen in her œuvre catalogue of Boeckhorst includes the cartoons under ‘uncertain and rejected pictures’. Jaffé thought that his arguments for Rubens’s authorship were confirmed by the fact that the Italian provenance of the Cardiff cartoons was discovered in 1986: they had been present in the collection of Cardinal Cesare Monti (1593–1650) in Milan in 1650, with the comment sono dissegni coloriti di Rubens (they are coloured drawings by Rubens).54 Moreover two tapestries had been found related to two of the four cartoons, one in Cardiff (Related works, no. 4d.II) and one in a private collection in Italy (Related works, no. 4a.II). Inscriptions in the borders prove that the tapestries and the cartoons depict a Romulus series. As there is a clear link between one of the Cardiff cartoons (Related works, no. 4b) [6] and DPG19, it is quite certain that the subject of DPG19 is Romulus. However Rubens’s authorship of the cartoons remains problematic. Although in 1650 in Milan the cartoons were considered to be by Rubens, at the time Milan was not known as a centre of Rubens art works or of Rubens collectors or scholars.

According to McGrath, Rubens designed two cycles on the theme of Romulus probably before 1626, and she considers the Cardiff cartoons to be part of the second set. They were executed by another artist, who after Rubens’s death took over the project and changed the compositions radically. Nevertheless they came to Italy under the name of Rubens.55 McGrath suggested that the sketch linked to the Dulwich version (Related works, no. 1) could be a modello by the artist who adapted Rubens’s original composition to create the Cardiff cartoons. The name that has been mentioned as the author of the other Romulus series is Justus van Egmont (1602–74), who was working in Rubens’s studio in the 1620s and who later became a tapestry designer.56 Two related tapestry cartoons in Sarasota (Related works, nos 6a–b) are attributed to Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert (1613/14–54), again an artist who collaborated with Rubens.57

The story of Romulus and Acron is recounted in a number of Classical sources. After the establishment of the city Romulus set out to remedy the lack of women by abducting them from a nearby people, the Sabines. One of the Sabine rulers, Acron, King of Caeninenses, sent an army against Rome in retaliation, but the two kings agreed to fight each other in single combat, with Romulus vowing to Jupiter Feretrius that if he won he would dedicate his adversary’s armour to the god. Romulus won the duel, incorporated the citizens of the vanquished city into Rome, and erected the trophy, as depicted in DPG19. Held suggested that the artist based his image largely on Plutarch’s account of the victory (Romulus, XVI, 5–8):

Romulus, that he might perform his vow in the most acceptable manner to Jupiter, and withal make the pomp of it delightful to the eye of the city, cut down a tall oak which he saw growing in the camp, which he trimmed to the shape of a trophy, and fastened on it Acron’s whole suit of armour disposed in proper form; then he himself, girding his clothes about him, and crowning his head with a laurel garland, his hair gracefully flowing, carried the trophy resting erect upon his right shoulder, and so marched on, singing songs of triumph, and his whole army following after, the citizens all receiving him with acclamations of joy and wonder. The procession of this day was the origin and model of all after triumphs.58

McGrath paid particular attention to the textual sources of the Romulus carrying the Trophy of Acron scene, and concurs with Held that the scene largely derives from Plutarch, noting that Rubens follows him in showing Romulus carrying the spolia opima or trophy on foot and in depicting the ferculum as a wooden pole on which the armour was hung.59 She noted, however, that Rubens took the setting of the scene on a slope and under a tree not from Plutarch’s sketchy account but from Livy (Ab urbe condita, I.x), who described Romulus ascending the Capitol:

He [Romulus] routed their army and put it to flight, followed in pursuit of it when routed, cut down their king in battle and stripped him of his armour, and, having slain the enemy's leader, took the city at the first assault. Then, having led back his victorious army, being a man both distinguished for his achievements, and one equally skilful at putting them in the most favourable light, he ascended the Capitol, carrying suspended on a portable frame, cleverly contrived for that purpose, the spoils of the enemy's general, whom he had slain: there, having laid them down at the foot of an oak held sacred by the shepherds, at the same time that he presented the offering, he marked out the boundaries for a temple of Jupiter, and bestowed a surname on the god. ‘Jupiter Feretrius,’ said he, ‘I, King Romulus, victorious over my foes, offer to thee these royal arms, and dedicate to thee a temple within those quarters, which I have just now marked out in my mind, to be a resting-place for the spolia opima, which posterity, following my example, shall bring hither on slaying the kings or generals of the enemy.’60

A picture with Mars and Rhea Silvia, the parents of Romulus and Remus, a scene that belongs to an earlier phase of the Romulus story, was related to the Romulus sketches, including DPG19. That picture however and the modello for it (Related works, nos 5a–b) must have been made earlier.61

Held pointed out that one of Rubens’s pictorial sources may have been the reverse of an ancient coin reproduced in an engraving in the book Fasti Magistratuum et Triumphorum Romanorum ab Urbe Condita by Hubert Goltzius (1526–83), reprinted in 1645. This showed Romulus on foot holding the trophy in one hand and with the other holding a spear over his shoulder (Related works, no. 13d) [10]. However, more Antique men in armour were studied by Rubens, as is seen in his work after the Gemma Tiberiana (Related works, nos 13a–c). Rubens used such studies for compositions with stories from Antiquity, the Bible, or more recent history (Related works, nos 7–11).62 Later Romulus series were also known to Rubens, such as that in the Palazzo Magnani in Bologna, by one or more of the Carracci brothers (Related works, nos 12b.I–II), but the posture of Romulus in DPG19 looks more like a somewhat earlier St Maurice by Guido Reni (1575–1642; Related works, no. 12a) than like the Carracci Romulus.

Rubens was interested in armour and even possessed a burgonet, which he thought to be Antique; he studied it in at least one drawing (Related works, no. 14b.I) [11] and used it again in a painting (Related works, no. 14c). In the Liechtenstein Collection in Vienna there is a modello for an entre-fenêtre, a narrow tapestry that hangs between two windows, which shows a picturesque accumulation of weapons (and a severed head). It is quite possible that in DPG19 Rubens depicted an existing burgonet, since some 16th-century ones have survived (Related works, nos 14a.I–II). Rubens’s helmeted warriors in turn inspired Jacques Jordaens I (1593–1678; Related works, nos 14d.I–II).

DPG19

Peter Paul Rubens

Romulus setting up a Trophy, c. 1622-1626

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG19

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1630-1634

Jeruzalem (city, Israel), The Israel Museum, inv./cat.nr. B86.0910

3

after Peter Paul Rubens

Reconciliation of Romulus and Titus Tatius, c. 1630-1635

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 2300 (OK)

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Romulus appearing to Julius Proculus, c. 1630-1634

Whereabouts unknown

6

after Peter Paul Rubens possibly Jan Boeckhorst

Romulus setting up a Trophy on the Capitol, c. 1635-1650

Cardiff (city, Wales), National Museum Cardiff, inv./cat.nr. NMW A230

9

Peter Paul Rubens

Roman warrior, c. 1614-1616

New York City, Zürich, art dealer David Koetser

10

Hubert Goltzius

Scenes from the life of Romulus, 1645

Whereabouts unknown

11

studio of Peter Paul Rubens and touched up by Peter Paul Rubens after Filippo Negroli

Parade burgonet in the shape of a dolphin, 1628-1636

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, inv./cat.nr. MS. Dupuy 667, fol. 159r

Notes

1 According to McGrath (1997, i, p. 151) the dimensions are 51 x 16.8 cm.

2 According to McGrath (1997, i, p. 153, note 2), who refers to Grossmann 1948, the width was 34.3 cm before the restoration, but the dimensions given in Grossmann (pp. 47 and 52) are 49 x 15 cm.

3 Archivio di Stato di Venezia. Inquisitorato alle Acque 49, Filza No. 9 ii, 1740 – Inventario della Eredità del qm. Sigr. Antonio Pellegrini qm. altro Sigr. Antonio […] In una Camera sopra la Terrazza: […] Altro [quadro] con Trofeo – Tutti con soaza dorata (Inventory of the inheritance of Mr Antonio Pellegrini [it is not known what other Antonio is referred to here] […] In a room above the terrace […] Another [picture] with a Trophy – all with gilt frames); see Vivian 1962, pp. 331–2.

4 Blunt & Croft-Murray 1957, Appendix A, p. 20. On p. 19 they say: ‘the copy [of the inventory] does not seem to be very accurate […] where the dimensions given can be checked […] they are demonstrably wrong’.

5 McGrath 1997, i, p. 153, has noted that the dimensions of the panel given in the 1794 sale catalogue are larger than DPG19, but it seems likely that these either referred to the framed size of the image or included the lateral additions which were removed in the 1940s.

6 ‘SIR P. P. RUBENS. A Man carrying Armour. A warrior armed, all but helmet, is bearing off a military trophy on a stand, consisting of cuirass, helmet, sword, &c.; he grasps it firmly in his right arm, extends his left towards heaven, and looks upwards as thankful for his success.’

7 ‘A Study doubtless by Rubens. S.P.D. A Roman soldier holding a trophy. Probably made for one of his larger pictures. Desenfans called it “Achilles contemplating armour” and valued it £60.’

8 GPID (26 Feb. 2014); McGrath 1997, i, p. 154, no. 30a.

9 RKD, no. 274716: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/274716 (July 13, 2019); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 86, ii, pp. 154–6, no. 31; Jaffé 1989, pp. 372–3, no. 1388; Held 1980, i, pp. 376–7, no. 281, ii, pl. 281.

10 RKD, no. 5522: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/5522 (July 13, 2019); see also http://collectie.boijmans.nl/nl/object/3583 (Aug. 29, 2019); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 87, ii, pp. 156–8, no. 31a (copy); Jaffé 1989, pp. 372–3, no. 1387; Giltaij 1983, pp. 70–72, no. 14; Held 1980, i, p. 376, no. 280, ii, pl. 280. Although Held and Jaffé consider this to be by Rubens, McGrath thinks it is probably a copy; the museum website says ‘attributed to Rubens’.

11 RKD, no. 274717: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/274717 (July 13, 2019); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 91, ii, pp. 158–61, no. 32; Bodart 1990, pp. 136–7, no. 48; Jaffé 1989, pp. 373–4, no. 1393; Held 1980, i, pp. 378–9, no. 282, ii, pl. 282.

12 RKD, no. 281397: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/281397 (July 13, 2019); Galen 2012, pp. 385–8, no. A 37 (under uncertain and rejected paintings by Boeckhorst); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 83, ii, pp. 115–17; Jaffé 1989, p. 373, no. 1392.

13 Galen 2012, p. 388, under no. A37 (note 729); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 84, ii, pp. 119, 129, Series I, no. 1.

14 RKD, no. 281388: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/281388 (July 13, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 192, fig. 19, under DPG19 (as Peter Paul Rubens); Galen 2012, pp. 385–9, no. A 38 (under uncertain and rejected paintings by Boeckhorst); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 85, ii, pp. 115–17; Jaffé 1989, p. 373, no. 1391.

15 RKD, no. 281393: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/281393 (July 13, 2019); Galen 2012, pp. 385–91, no. A 39 (under uncertain and rejected paintings by Boeckhorst); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 86, ii, pp. 115–17; Jaffé 1989, pp. 372–3, no. 1389.

16 RKD, no. 281394: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/281394 (July 13, 2019); Galen 2012, pp. 385–95, no. A 40 (under uncertain and rejected paintings by Boeckhorst); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 90, ii, pp. 115–17; Jaffé 1989, p. 374, no. 1394.

17 Galen 2012, p. 395, under no. A40 (note 735); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 94, ii, p. 129, Series I, no. 2.

18 325 RKD, no. 194272: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/194272 (July 13, 2019); see also RKD, no. 185379: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/185379 (Sept. 3, 2019; the triptych closed), RKD, no. 194273: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/194273 (Sept. 3, 2019; left wing) and RKD, no. 194274: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/194274 (Sept. 3, 2019; right wing); see also https://collections.lacma.org/node/215610 (July 7, 2019); Galen 2012, pp. 194–9, no. 72.

19 N. Lowitzsch in Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2004, pp. 188–93, no. 40; McGrath 1997, i, fig. 102, ii, p. 142; Jaffé 1989, p. 225, no. 416.

20 N. Lowitzsch in Kräftner, Seipel and Trnek 2004, pp. 194–5, no. 41; McGrath 1997, i, fig. 101, ii, p. 142; Jaffé 1989, p. 226, no. 417.

21 RKD, no. 10588: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/10588 (July 13, 2019); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 95, ii, pp. 120–22; Robinson, Wilson & Silver 1980, n.p., no. 56.

22 According to the museum website (2 Sept. 2019) these are Two Remus subjects. McGrath 1997, i, fig. 96, ii, pp. 120–22 (Death of Turnus and another subject); Robinson, Wilson & Silver 1980, n.p., no. 55 (Remus before Amulius).

23 RKD, no. 224309: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/224309 (July 13, 2019); see also http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2008/old-master-paintings-evening-sale-l08033/lot.20.html (Aug. 29, 2019); Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 168–70, no. 14, ii, fig. 82; Jaffé 1989, p. 198, no. 265; Held 1980, i, p. 593, no. 431, ii, pl. 419.

24 RKD, no. 12543: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/12543 (July 13, 2019); Wheelock 2005, pp. 175–82, no. 1957.14.2; Jaffé 1989, pp. 214–15, no. 351.

25 RKD, no. 271467: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/271467 (July 13, 2019); Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 136–41, no. 30 (M. Seipel); Jaffé 1989, p. 215, no. 357.

26 RKD, no. 271477: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/271477 (July 13, 2019); Gaddi 2010, pp. 106–7, no. 11 (M. Seipel); Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 180–81, no. 37 (M. Seipel); Baumstark 1985, p. 355, no. 217.

27 Ingamells 1992, pp. 330–32, no. P523; see also under P522, p. 327; Jaffé 1989, p. 310, note 951.

28 RKD, no. 19090: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/19090 (July 13, 2019); Freedberg 1995, pp. 50–53; Jaffé 1989, p. 267, no. 684.

29 RKD, no. 228429: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/228429 (July 13, 2019); Büttner & Heinen 2004, pp. 151–5, no. 15; Jaffé 1989, p. 323, no. 1027 (1630–31); Held 1980, i, pp. 316–17, no. 230 (c. 1635–7), ii, pl. 252.

30 Cifani, Moretti & Pepper 1990.

31 McGrath 1997, ii, p. 117, i, figs 92, 93. Emiliani 1989, figs X, XLIII, p. 162, no. 8, p. 182, no. VIII.

32 https://www.teylersmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/kunst/kg-14527-romulus-geeft-de-overwinningsbuit-op-koning-acron-aan-iupiter-feretrius (July 13, 2019).

33 Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), pp. 188–9, under no. 168, iii (1995), fig. 324.

34 RKD, no. 273928: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/273928 (July 13, 2019); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), pp. 190–91, no. 168a, iii (1995), fig. 322.

35 RKD, no. 39928: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/39928 (July 13, 2019); see also https://www.ashmoleanprints.com/image/411042/sir-peter-paul-rubens-the-apotheosis-of-germanicus-copy-after-an-Antique-cameo-the-gemma-tiberiana (July 13, 2019); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), pp. 191–2, no. 168b, iii (1995), fig. 325.

36 RKD, no. 295343: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295343 (Oct. 8, 2019); McGrath 1997, i, fig. 105, ii, pp. 152–3 (she also noted a similar coin illustrated by De Bie in his Numismata (1617), ibid., p. 153 (note 14); see Held 1980, i, p. 376. The coin depicted second from below on the right shows Romulus (in reverse) with the trophy on his left shoulder and a spear in his right hand; it is inscribed Romulo Augusto (and other Latin inscriptions); also in Held 1981, p. 62 (text fig. 8).

37 Soler del Campo 2009, pp. 116–17, no. 25.

38 https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultDetailView/result.t1.collection_detail.$TspImage.link&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=1&sp=2&sp=SdetailView&sp=0&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F(Aug. 13, 2020); Mann 1962, pp. 111–12, pl. 61; Norman 1986, p. 49, no. A 106; Capwell 2011, pp. 102–3, no. A 106.

39 RKD, no. 295228: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295228 (Oct. 8, 2019); Wood 2011, i, pp. 399–402, no. 247, ii, fig. 231; F. Healy in Belkin & Healy 2004, p. 296 (fig. 78a), under no. 78; Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), pp. 125–6, text ill. 76–7.

40 Wood 2011, i, p. 401, ii, fig. 237.

41 RKD, no. 56428: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/56428 (July 13, 2019); Freedberg 1995, pp. 26–9; Van der Meulen 1994–5, i (1994), p. 126 (note 139), text. ill. 79.

42 Joconde (11 Feb. 2014); Nelson 1998, pp. 136 (no. 48a), 301 (fig. 104); D’Hulst 1974, ii, pp. 471–2, no. A414, iv, fig. 441.

43 RKD, no. 234286: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/234286 (July 13, 2019); Nelson 1998, pp. 136 (no. 48 (1A)), 300 (fig. 102), where other tapestries are also mentioned.

44 RKD, no. 17304: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/17304 (with provenance; July 13, 2019); see also Jaffé 1989, pp. 357, no. 1271; Alpers 1971, pp. 211–12, no. 24a.

45 RKD, no. 229127: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/229127 (July 13, 2019); see also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/el-rapto-de-ganimedes/ (Feb. 14, 2014); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 944–5, no. 1679; Jaffé 1989, pp. 357–8, no. 1272; Alpers 1971, pp. 210–11, no. 24, fig. 100.

46 Held 1980, i, pp. 587–9, no. 427, ii, pl. 418. McGrath here differs from Held: he dates this sketch for an altarpiece in the Antwerp Museum 1630–33, whereas she says that the sketches, including DPG19, were made before 1626. See note 48 below.

47 Jaffé 1988a, p. 15, pl. IIIb; Held 1980, i, pp. 79–80, no. 46, ii, pl. 47.

48 McGrath 1997, ii, p. 124.

49 Aikema & Mijnlieff 1993.

50 According to Blunt & Croft-Murray 1957 the dimensions in this inventory tend to be wrong: see note 4 above.

51 Held 1980, i, pp. 375–9, nos 279–82, ii, pl. 279–82; see also McGrath 1997, ii, p. 117.

52 Boeckhorst is known to have worked with Rubens in the 1630s, and he completed at least two unfinished paintings by Rubens: Vlieghe 1990b, pp. 75–81; Van Tichelen & Vlieghe 1990, pp. 112–13; Vlieghe 1987a, p. 599.

53 McGrath 1997, ii, p. 123; Jaffé 1983c.

54 Jaffé & Cannon-Brookes 1986.

55 McGrath 1997, ii, p. 116.

56 ibid., p. 128

57 Vlieghe attributes them to Jan Boeckhorst: Vlieghe 1983 and Van Tichelen & Vlieghe 1990, pp. 110–13.

58 Transl. John Dryden, see http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Plutarch/romulus.html (Jan. 12, 2021). For the development of Roman triumphs see Holliday 2002, pp. 22–62.

59 Dionysus of Halicarnassus (Roman Antiquities, II.33.2–II.34.4) presented Romulus as riding to the capitol in a quadriga or four-horse chariot. Plutarch seems to take the authenticity of other authors to task, as he stresses that in Rome the statues of Romulus with the trophy all depicted the king on foot: McGrath 1997, i, p. 152.

60 Livy 2009, pp. 37–8.

61 The relation to the Romulus sketches had been suggested by Baumstark, as cited in McGrath 1997, ii, pp. 124, 137/8 (note 86); for the related tapestry see ibid., ii, pp. 140–43.

62 However, according to Rodee 1967, p. 223, ‘Rubens goes far beyond his contemporaries in his inaccuracy’ in depicting Antique armour. He was more precise with contemporary armour, but ‘Surprising as it may seem, there is not a single painting by Rubens showing groups of armored men that is completely accurate throughout’, ibid., p. 226.