Peter Paul Rubens DPG143

DPG143 – Portrait of a Lady (Katherine (or Catherine) Manners, Duchess of Buckingham?)

1625; oak panel, 79.7 x 65.7 cm1

PROVENANCE

?2; Desenfans sale, Skinner and Dyke, 18 March 1802 (Lugt 6380), lot 175; Desenfans 1802, pp. 29–31, no. 88 (Rubens, A Portrait of Marie de Medici);3 Insurance 1804, no. 86 (‘Mary de Medicis – Rubens . £150’); Britton 1813, p. 29, no. 299 (‘Unhung; no. 30; Portrait of Mary de Medicis – C[anvas] Rubens’; 3'4" x 2'10").

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 7, no. 91 (‘SECOND ROOM – South side; Portrait of Mary de Medici; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 377, no. 91; Cat. 1820, p. 7, no. 91 (Maria de Medici; Rubens); Cat. 1830, no 187 ((after) Rubens); Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 200, no. 726 (‘Mary de Medicis’; ‘Painted by a scholar.’), ‘100 gs.’; Jameson 1842, ii, p. 472, no. 187;4 Bentley’s 1851, p. 348;5 Denning 1858 and 1859, no. 187 (copy after Rubens);6 Sparkes 1876, p. 152, no. 187 (School of Rubens); Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 144, no. 187 (under ‘painted in the style of Rubens by his scholars or imitators; Portrait of a Lady’);7 Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 37, no. 143 (Portrait of a Lady; School of Rubens); Cook 1914, p. 86, no. 143 (Rubens); Cook 1926, p. 81, no. 143; Glück & Haberditzl 1928, p. 50, under no. 157 (Catherine Manners, DPG143 a contemporary copy); Glück 1940, p. 174 (by or after Rubens), pl. IIIb;8 deposition by L. Burchard asserting Rubens’s authorship, also of the verso (DPG143 file, 25 Sept. 1945); Grossmann 1948, pp. 51 (fig. 37; Catherine Manners), 52–4; Cat. 1953, p. 35 (Rubens; Catherine Manners); Paintings 1954, pp. 19, [60]; Sutton 1954, pp. 40, 70 (note 26: not Catherine Manners);9 Grossmann 1957a, p. 6 (Catherine Manners, after a miniature by Balthasar Gerbier); Norris 1957, p. 125 (not Catherine Manners, c. 1625); Grossmann 1957b, p. 126 (Catherine Manners); Held 1959, i, p. 138 (Catherine Manners), under no. 107 (Related works, no. 1b.1); Fletcher 1968, pp. 16, 86, pl. 23; Morawińska 1974, p. 41, no. 25, fig. 44; Huemer 1977, pp. 110–13, no. 6 and 6a (Katherine Manners (?) or unknown lady at the French court, c. 1625), fig. 57; Mitsch 1977, p. 96 (fig.), under no. 40 (Related works, no. 1a) [1]; Murray 1980a, pp. 113–14 (Katherine Manners, Duchess of Buckingham (?)); Murray 1980b, p. 25; Lecaldano 1980, ii, pp. 132–3, no. 800 (1629–30); Bodart 1985, p. 185, no. 642; Held 1986, p. 134; Jaffé 1989, p. 285, no. 790 (Katherine Manners, c. 1625);10 Jaffé 1990, pp. 699–700 (Katherine Manners); Wood 1992a, p. 827, no. 65.2;11 Wood 1992b, pp. 43, 47 (note 72); Barber 1995, p. 168, under no. 115 (Related works, no. 1b.1) [2]; Beresford 1998, p. 210; Laing 1999, p. 549 (French lady); Díaz Padrón & Padrón Mérida 1999, p. 176, under no. 64 (Van Dyck, Sir George Villiers and Katherine Manners as Adonis and Venus, Related works, no. 3i) [4]; Merle du Bourg 2004, p. 62 (not Katherine Manners);12 Logan & Plomp 2004b, p. 366, note 1, under nos 87–8; Logan & Plomp 2004c, p. 230, note 2, under no. 77 (Related works, no. 1b.I) [2]; Meek 1993, p. 19; Tyers 2014, pp. 25–7; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 189–91, 213; RKD, no. 255163: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/255163 (July 18, 2019).

EXHIBITIONS

London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 40 (L. Burchard; Rubens; Katherine Manners); London 1950–51, p. 98, no. 227; Paris 1952–3, p. 59, no. 76 (Rubens; Katherine Manners); London 1953–4, p. 71, no. 216; Bruges 1956, pp. 56–7, no. 73 (unknown lady at the French court, c. 1625; unfinished original), fig. 55; Antwerp edn of Cologne/Antwerp/Vienna 1992–3, p. 150, no. 62 (H. Vlieghe; Katherine Manners as a widow; c. 1629–30 (?); prototype); Cologne edn of Cologne/Antwerp/Vienna 1992–3, p. 407, no. 65.2 (cf. Antwerp edn); Japan 1999, p. 168, no. 27 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 138–9, no. 41 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Vienna 2004, pp. 374–7, no. 91 (H. Widauer).

TECHNICAL NOTES

The support consists of a three-member oak panel with vertical grain. There is almost no warp. The panel is thicker at the centre and tapers at the sides, which can be seen at the top and bottom edges. There is a 10 cm split at the bottom right. The verso has white gesso priming, painted brown, and there are traces of a rough drawing beneath, which can be made out slightly more clearly in UV: it appears to depict a female figure. It is unclear whether the verso sketch is by Rubens.13 There is a thin, broadly applied grey imprimatura, typical of Rubens, applied over the chalk ground on the front of the panel. In places (such as the face, the hair and the ribboned sleeves) the paint surface is detailed and highly worked, but the cuffs and the proper right hand are sketchy, broadly painted and unfinished. The reserve, left when the red background was painted, can be seen at the edge of the proper right cuff. The collar may also be unfinished but it is painted in more detail than the cuffs. There seems to be slight abrasion of the black passages and around the sitter’s waist. The mauve dress and ribbons have faded, probably due to the discolouration of a light-sensitive lake pigment: a strip along the bottom, which has been protected by the frame rebate, remains closer to the original shade. Previous recorded treatment: 1871, ‘revived’, varnished and frame regilded; 1931, frame paraffined to treat for woodworm; 1935, frame paraffined; 2004, conserved, S. Plender.

RELATED WORKS

1a) (Preparatory (?) drawing for the face) Peter Paul Rubens, Katherine Manners, Duchess of Buckingham, c. 1625 or c. 1629, inscribed in red chalk in another, 17th-century, hand: Hertoginne van Bockengem P.P. Rubbens f., black and red chalk, heightened with white bodycolour, 368 x 265 mm. Albertina, Vienna, 8257 [1].14

1b.I) (pendant of 1a?) Peter Paul Rubens, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, c. 1625, inscribed in red chalk in another hand: hertoeg van bockengem P.P Rubbens. ft, black and red chalk, heightened with white bodycolour, 383 x 266 mm. Albertina, Vienna, 8256 [2].15

1b.II) (after 1b.I) Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of George Villiers (1592–1628), Duke of Buckingham, c. 1625, canvas, 60.9 x 47.3 cm. Pollok House, Glasgow, PC.49.16

1b.III) (pair of 1b.IV?) Studio of or copy after Peter Paul Rubens, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, after 1625, panel, 63 x 48 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Florence, 324.17

1b.IV) (pair of 1b.III?) Studio of or copy after Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of a Lady (Katherine Manners?), panel, 64 x 46 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Florence, 1890 note 761.18

2) (possible pair of DPG143) English School, 17th century, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, panel, 78 x 62 cm. Collection Earl of Jersey.19

(Other) portraits of Katherine (Catherine) Manners

3a) Gerard van Honthorst, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham with his Family, 1628 (?), canvas, 132.5 x 192.8 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 406553 [3].20

3b) Attributed to Henri Beaubrun, Lady Katherine Manners, Widow of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, c. 1628–32, canvas, 59.7 x 48.9 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Philip Mould Ltd, London, 2010s).21

3c) Anthony van Dyck, Katherine, Duchess of Buckingham with her Children, Mary, George and Francis Villiers, c. 1633, canvas, 234.6 x 182.6 cm. Rubenshuis, Antwerp, RH.S.188.22

3d) Anthony van Dyck, Katherine, Duchess of Buckingham, later Countess, and ultimately Marchioness, of Antrim as Widow, c. 1633, canvas, 74 x 57.5 cm. The Duke of Rutland collection, Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire.23

3e) Anthony van Dyck, Katherine, Duchess of Buckingham, later Countess, and ultimately Marchioness, of Antrim, before April 1635, canvas, 219.7 x 132.7 cm (including an early addition at the top). The Marquess of Anglesey and the National Trust collection, Plas Newydd, Anglesey.24

3f) Magdalena de Passe, Katherine Manners, Duchess of Buckingham and Marchioness of Antrim, inscriptions, engraving, 123 x 83 mm. BM, London, P.1.281.25

3h) Anthony van Dyck, The Continence of Scipio, canvas, 183 x 232.5 cm. Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, JBS 245.26

3i) Anthony van Dyck, Venus and Adonis, c. 1620–21, canvas, 223.5 x 160 cm. Private European collection [4].27

Portraits of other ladies

4a) Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of a Woman (of the Lunden or Fourment family), c. 1625–30, panel, 84.8 x 59.3 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 400118.28

4b) Frans Pourbus II, Maria de’ Medici, Queen of France (1573–1642) as a Widow, 1610–20, canvas, 65.50 x 57 cm. Musée Carnavalet, Paris, P 2338.29

4c) (studio of) Peter Paul Rubens, Anne of Austria, Queen of France, c. 1625, panel, 105 x 74 cm. Van der Hoop Collection, City of Amsterdam, on loan to RM, Amsterdam, SK-C-296.30

4d) Peter Paul Rubens, Madame de Vicq, 1625, panel, 73.4 x 53 cm. Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 93.54 [5].31

Copies

5a) Copy (without the hands): Flemish school c. 1800, canvas, 63 x 42 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Piasa sale, Paris, 25 June 2002, lot 86).32

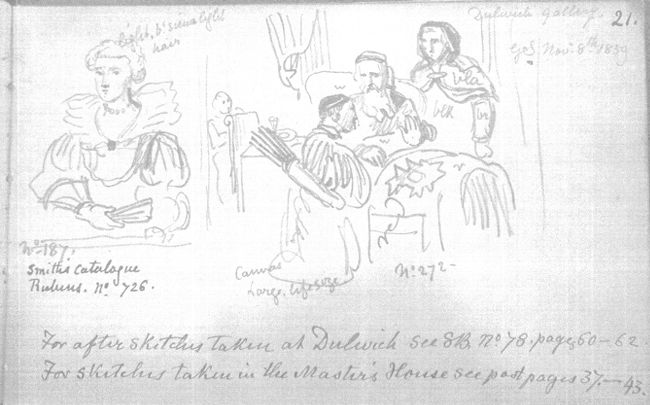

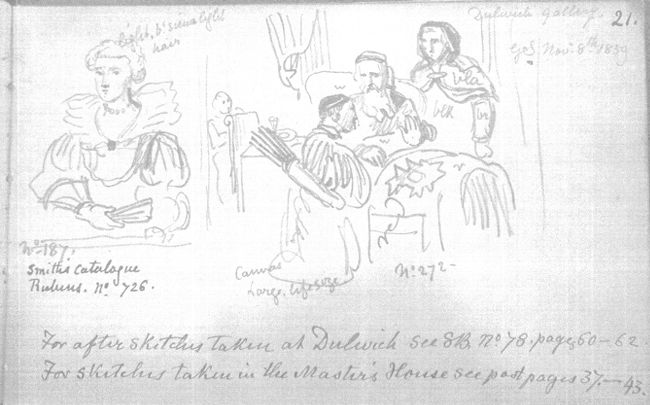

5b) Copy: in George Scharf sketchbook: top right, ‘Dulwich Gallery GS Nov 8th 1859’; left, below image of portrait, ‘No. 187: Smith’s catalogue Rubens No. 726’; right of image of portrait, ‘light, bd siena light hair’.33 National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG7/3/4/2/89, p. 21 [6].

DPG143

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of a Woman (Katherine Manners, duchess of Buckingham; 1603-1649?), c. 1625

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG143

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of Katherine Manners, duchess of Buckingham (1603-1649), c. 1625

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 8257

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of George Villiers (1592-1628), Duke of Buckingham, to be dated 1625

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 8256

3

Gerard van Honthorst

Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) with his family, 1628

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406553

4

Anthony van Dyck and studio of Anthony van Dyck

Portrait historié of an unknown man and a woman as Adonis en Venus, c. 1620-1621

Switzerland, Belgium, private collection Eric and Marie-Louise Albada Jelgersma

5

Peter Paul Rubens

Portret of Hypolite de Male (?-?), wife of Henri de Vicq, seigneur de Meulevelt (1573-1651), dated 1625

Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 93.54

6

George Scharf (II)

Copy of Rubens's Portrait of Katherine Manners (?) (DPG143) and of Horst's Isaac Blessing Jacob (DPG214), 1859

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG7/3/4/2/68, p. 21

DPG143 depicts a woman in a purple, white and black dress with a white lace double collar, holding a fan, against a red background. Only the head is completed; the lilac strips over the white sleeves, and the lilac bodice, are nearly finished. On the basis that one of the sitter’s hands is not visible, Huemer in 1977 suggested that the picture had been cut at the bottom and possibly on the right.34 Since a – rather rubbed – drawing by Rubens in Vienna depicts only the head of the subject (Related works, no. 1a) [1], it could be that the rest of the picture was left to his assistants, or perhaps Rubens or his patron was unsatisfied with the design and so it was left incomplete. There are small differences between the drawing and the picture: in the drawing the sitter does not wear a diadem in her hair, which is dressed differently. Mitsch in 1977 asserted that the Vienna drawing was a preparatory one, because in the lower right-hand corner there is a profile of a lady; that seems to indicate that Rubens himself was at work and not another artist making a copy after him, but a copyist can also make sketches.

In September 1945 Ludwig Burchard found that the back of the panel was used for a sketch for a mythological composition, indicating that Rubens must have retained the picture.35 In any case the back has a complete primer for painting. In Rubens’s inventory, just before no. 127, Le portrait du duc de Boucquingam (Portrait of the Duke of Buckingham), no. 126 is called Vn Pourtrait d’vne Dame (in the English list, ‘Portrait of a Certayne Lady’),36 which might be DPG143.

The Vienna drawing has a pair in a drawing of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (Related works, no. 1b.I) [2]. After that drawing, which is much better preserved, Rubens had made an oil painting, of which there is a copy in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence (Related works, no. 1b.III). In 2017 the original was discovered after restoration in Glasgow (Related works, no.1b.II). In the Palazzo Pitti as in Vienna the Duke has a pair, in this case in an oil painting depicting a different blonde, also called Katherine Manners (Related works, no. 1b.IV). She however seems to derive from a painting in the British Royal Collection which probably depicts a member of the Lunden or Fourment family (Related works, no. 4a). In the drawings in Vienna and in the paintings in Florence the sitters look in the same direction, which is not usual for pairs. The question is whether they are really pairs. One of the few portraits of the Duke of Buckingham which looks in the opposite direction from that in DPG143 has only survived in a copy in the collection of the Earl of Jersey (Related works, no. 2).

In early Dulwich catalogues the lady in DPG143 was identified as Queen ‘Mary de Medicis’ (1573–1642; cf. Related works, no. 4b), the second wife of Henry IV of France (1553–1610), who she clearly is not. Later DPG143 was called ‘Portrait of a Lady’. Glück and Haberditzl in 1928 were the first to relate the sketch in Vienna and DPG143 to each other, and noted that the inscription Hertoginne van Bockengem on the former (by another, 17th-century, hand) called the sitter Duchess of Buckingham – at the time Lady Katherine Manners (c. 1603–49). This drawing belongs to a series with similar inscriptions indicating the sitters, which proved mostly to be right. This lady, daughter of the Earl of Rutland, married George Villiers, then Marquess (later 1st Duke) of Buckingham, in May 1620. After Buckingham was assassinated in 1628, she married Randal McDonnell, Earl of Antrim.

The identification is problematic. Portraits of Katherine Manners seem to depict two different women. In the pictures made later in her life by Gerard van Honthorst (1592–1656; Related works, no. 3a, 1628) [3], Henri Beaubrun (1603–77; Related works, no. 3b), and Anthony van Dyck (Related works, nos 3c–e, 1630s) she is a brunette with a rather large nose. She is a blonde with a more pointed nose in earlier portraits historiés by Van Dyck (with Buckingham, 1620–21; Related works, nos 3h–i) [4] and supposed pendants of portraits of Buckingham (the aforementioned pairs, the drawings in Vienna and the pictures in the Palazzo Pitti); these were all doubted to depict Katherine Manners because the lady does not look like the brunette. The colour of the hair is not the problem – the ladies at the court of Queen Henrietta Maria (1609–69) in London were known to dye their hair – but the shape of the nose. The face and the form of the nose of Venus in Venus and Adonis by Van Dyck, thought to depict the Villiers/Manners couple, are very similar to those of the lady in DPG143, but some scholars still doubt that identification.37

Another problem is that Katherine Manners is not known to have left England. Rubens’s only opportunity to paint her from life would have been in 1629–30, when he was in London. Rubens and the Duke of Buckingham met in Paris in 1625. Rubens was there to finish the Medici cycle in the Palais du Luxembourg (about the history of Maria de’ Medici, as princess, queen, and regent for her son, the future Louis XIII), now in the Louvre.38 Buckingham was in Paris to bring Henrietta Maria, daughter of Maria de’ Medici and Henri IV, bride-to-be of King Charles I, back with him to London. He commissioned from Rubens not only the drawings of himself and Katherine Manners (?) which were the basis of the pictures, but also other works of art glorifying himself.39 In 1627 Rubens sold Buckingham his collection of antiquities, which he had acquired from Dudley Carleton (1573–1632) in 1618.40

Grossmann in 1957 suggested that DPG143 might have been painted in Paris in 1625, but based on a portrait by Balthazar Gerbier d’Ouvilly (1591/3–1663). It is indeed conceivable that the Duke commissioned Rubens to produce a portrait of the Duchess for which he gave him as model a miniature he had brought with him to Paris: this would explain the supposed lack of fidelity to Katherine Manners’ features.

According to Michael Jaffé, DPG143 depicts a woman in court dress, which was according to him ‘high Parisian mode’,41 but it should be noted that alternating dark and white slashed sleeves were also popular in England in the 1620s, as shown in several portraits from that period. Interestingly, the costume with its sleeves and jewellery is similar to those in two other portraits which must have been painted in France: Anne of Austria, Queen of France, to be dated c. 1625 (1601–66; Related works, no. 4c), and Madame de Vicq, dated 1625 (Tel Aviv Museum of Art; Related works, no. 4d) [5]. The subject could therefore be not Katherine Manners but a French lady-in-waiting, as some authors suggest.42 However, Bianca du Mortier has commented that the jewellery in DPG143 shows that the lady was excessively rich, which would point in the direction of Katherine Manners, who was at the time the richest woman in England.43

Some scholars have assumed that the black rosette was a sign of mourning, and that the lady was a widow at the time.44 If she were Katherine Manners, that would have been after the assassination of Buckingham in 1628. However black jewels were not a sign of mourning in the 17th century (memento mori pieces and pearls would have been worn instead),45 and, although the dress in DPG143 would have been a perfect example of half-mourning in the 19th century, in the 17th century a mourning dress would have been completely black, and the hair would have been covered.46

In conclusion, because of the similarity with Venus and Adonis in the Van Dyck picture, it is tempting to think that the lady in DPG143 is Katherine Manners. We would still need to explain why she looks in the same direction as her husband (in the drawings in Vienna), why the picture was left unfinished, and why Rubens seems to have kept it in his studio. The strongest counter-argument is that she looks much older than a twenty-two-year-old, if she was born around 1603, but that is also not certain.

Sir George Scharf, who in 1857 became Secretary of the National Portrait Gallery, and later its Director, on one of his many tours around the British Isles sketched some of the portraits in the Dulwich Gallery. In 1859 he drew three paintings that were thought to be by Rubens, DPG285, DPG290 and DPG143. The remarks he made next to his drawing of DPG143 relate to colours, and not to the sitter [6].

DPG143

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of a Woman (Katherine Manners, duchess of Buckingham; 1603-1649?), c. 1625

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG143

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of Katherine Manners, duchess of Buckingham (1603-1649), c. 1625

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 8257

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of George Villiers (1592-1628), Duke of Buckingham, to be dated 1625

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 8256

3

Gerard van Honthorst

Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) with his family, 1628

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406553

4

Anthony van Dyck and studio of Anthony van Dyck

Portrait historié of an unknown man and a woman as Adonis en Venus, c. 1620-1621

Switzerland, Belgium, private collection Eric and Marie-Louise Albada Jelgersma

5

Peter Paul Rubens

Portret of Hypolite de Male (?-?), wife of Henri de Vicq, seigneur de Meulevelt (1573-1651), dated 1625

Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 93.54

6

George Scharf (II)

Copy of Rubens's Portrait of Katherine Manners (?) (DPG143) and of Horst's Isaac Blessing Jacob (DPG214), 1859

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG7/3/4/2/68, p. 21

Notes

1 It seems that the panel was cut at the bottom and possibly at the right (Huemer 1977, p. 110); Plender 2004: ‘There seem to be marks where the wood has been cut, especially at the side edges.’

2 According to Huemer (1977, p. 110) this picture was purchased by Desenfans for the Polish King between 1790 and 1802. We do not know the evidence for that. DPG143 is first mentioned in the ‘Polish’ sale in 1802 (see Introduction).

3 372 ‘We know not from what cause, but almost every female portrait of this master’s [Rubens’s] hand, is misnamed and called the wife of Rubens who was never married but twice. If it happens that the picture is not like Helena his first, ’tis called his second wife, and if it resembles neither, they will have it that it is Rubens’s third, fourth, or fifth wife. It was under that denomination this was sold us, although it is the portrait of Mary de Medicis, Queen to Henry the Fourth of France, and mother to Lewis the Thirteenth.’ She is seen half-length, as large as life, and full face; her head is adorned with a diadem of precious stones, with large pearls in her ears; she is dressed in the fashion of the sixteenth century, when they wore those large puckered sleeves which gave an air of grandeur to women, and added still to their charms, by that raised ruff which left part of the bosom uncovered. She has on her neck, a row of pearls, and two others fastened below her shoulders, falling with elegance on her breast – in her bosom is seen a rose of the most precious stones, and her girdle is of the like jewels intermixed with pearls. She holds a fan in her hand, and there is on her countenance, a smile of benignity. A crimson curtain is in the background of this superb work, painted with the chastest colours that ever came from the palette of this great master.’

4 ‘I presume by one of Rubens’s scholars.’

5 ‘We first see “Mary de Medicis,” by Rubens; or, as some connoisseurs suppose, by one of Rubens’s scholars; a fair, plump, matronly lady, looking as unlike her historical reputation as possible.’

6 ‘It is probably painted by a scholar. “It is a copy made by some one who understood the style of Rubens” S.P.D.’

7 ‘Formerly called a portrait of Maria de’ Medici, to whom, however, it bears no resemblance whatever. When Mr. Desenfans bought it, it was described as representing the wife of Rubens.’

8 ‘a copy of which (if not an original, spoilt by repaints and dirty varnish) is still preserved in the Dulwich Gallery’.

9 According to Sutton DPG143 does not look like the Van Dyck portrait of her at Belvoir Castle (Related works, no. 3d): ‘It would seem that the Dulwich picture does not in fact represent the Duchess and that the inscription on the Vienna drawing is incorrect.’

10 If she is depicted as a widow (see the black rosette), then the date would be 1629–30, which Jaffé thinks unconvincing. However in the 17th century black was not a sign of mourning. See also notes 43–46.

11 ‘The identification is less secure than stated here. However the dating of 1629–30 is more persuasive than the conventional one of 1625.’ Wood comments here on the entry by H. Vlieghe in Mai & Vlieghe 1992, p. 407, no. 65.2.

12 However this author does not take into account the two portraits historiés by Van Dyck (Related works, nos 3h–i; Fig.); many thanks to Nico Van Hout, who brought this publication to our attention.

13 In September 1945 Ludwig Burchard identified this sketch as a mythological composition ‘for Hercules and Achelous and other figures’, which indicated to him that the artist must have retained the unfinished picture (Rub LB no. 1424 file).

14 RKD, no. 255166: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/255166 (Aug. 21, 2019); see also http://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/?query=Inventarnummer=[8257]&showtype=record (July 19, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 189–90 (fig. 18), 213 (note 110), under DPG143; H. Widauer in Schröder & Widauer 2004, pp. 374–7, no. 92; Huemer 1977, p. 113, no. 6a; Mitsch 1977, pp. 96–7, no. 40; Rooses 1886–92, v (1892), pp. 262–3, no. 1502.

15 RKD, no. 258891: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/258891 (Aug. 21, 2019); see also http://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/?query=Inventarnummer=[8256]&showtype=record (July 19, 2019); Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 228–30, no. 77; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 364–6, no. 87; Barber 1995; Vlieghe 1987b, pp. 63–4, no. 80a; Mitsch 1977, pp. 94–5, no. 39; Held 1959, i, p. 138, no. 107, ii, fig. 119.

16 RKD, no. 258888: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/258888 (Aug. 20, 2020); after restoration in 2017, authenticated as Peter Paul Rubens by Ben van Beneden.

17 RKD, no. 197935: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197935 (Aug. 21, 2019); Conticelli, Gennaioli & Sframeli 2017, p. 539, no. 76 (Duca di Buckingham); Schröder & Widauer 2004, pp. 364–7, no. 88; Chiarini & Padovani 2003, ii, pp. 356–7, no. 573a; Vlieghe 1987b, pp. 62–3, under no. 80 (copy); Bodart 1977, pp. 232–3, no. 99; Portrait 1952, p. 59, no. 75. The portraits of George Villiers and the blonde lady have been together in Florence since 1675. According to Bodart (1977, p. 232, no. 100) Related works, no. 1b.IV was inspired by a portrait of a lady in the Royal Collection (Related works, no. 4a). According to the same author the picture in Florence does not look like DPG143, the drawing in Vienna (Related works, no. 1) or Hélène Fourment (who was previously suggested as the sitter).

18 See the preceding note; http://www.gogmsite.net/transition_from_ruffs_to_co/subalbum-catherine-manners/lady-katherine-manners-by-p.html (July 19, 2019); Conticelli, Gennaioli & Sframeli 2017, p. 27 (figs 11 and 12; ritratto femminile), p. 538, no. 74 (Duchessa di Bucchingam); Chiarini & Padovani 2003, ii, pp. 356–7, no. 573b (M. Chiarini); Bodart 1977, pp. 232–3, no. 100; Portrait 1952, p. 59, no. 75a.

19 Jaffé 1990, p. 698 (fig. 29).

20 RKD, no. 294469: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294469 (Aug. 21, 2019); see also https://www.rct.uk/collection/406553/george-villiers-1st-duke-of-buckingham-1592-1628-with-his-family (July 19, 2019); Judson & Ekkart 1999, p. 284, no. 385, pl. 281; White 1982, pp. 56–7, no. 75, pl. 67. There are many copies, among them one in the National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG711).

21 http://www.historicalportraits.com/Gallery.asp?Page=Item&ItemID=597&Desc=Duchess-of-Buckingham-%7C-Attributed-to-Henri-Beaubrun (July 19, 2019).

22 RKD, no. 120577: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/120577 (July 19, 2019); Millar 2004, pp. 449–50, no. IV.31.

23 RKD, no. 240377: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/240377 (July 19, 2019); Millar 2004, pp. 450–51, no. IV.32.

24 RKD, no. 240379: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/240379 (July 19, 2019); Hearn 2009, p. 81, no. 32; Millar 2004, p. 451, no. IV.33.

25 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_P-1-281 (Aug. 2, 2020); the other two portraits of Katherine Manners on the BM website derive from this one (see P.1.279 and P.1.280).

26 RKD, no. 48884: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/48884 (July 19, 2019); Hearn 2009, pp. 48–9, no. 6 (T. Batchelor); O. Millar in De Poorter 2004, pp. 135–6, no. I.157 (design for a tapestry?); Brown & Elliott 2002, pp. 266–7, no. 58; Wood 1992b; Harris 1973; Weststeijn 2015, pp. 53–4 (fig. 37).

27 RKD, no. 229429: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/229429 (July 19, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2012, pp. 39, 69 (note 142); Van der Stighelen, Magnus & Watteeuw 2010, p. 151; O. Millar (in De Poorter 2004, p. 137, no. I.158) suggested that this picture was left unfinished by Van Dyck and later finished by another artist, although he adds: ‘At the Jacobean court there may not have been a painter capable of completing the picture even in this two-dimensional manner’; Elliott & Brown in Brown & Elliott 2002, pp. 168–71, no. 14; U. Weber-Woelk in Mai & Weber-Woelk 2000, pp. 310–11, no. 39; Díaz Padrón & Padrón Mérida 1999, pp. 176–7, no. 64; Howarth 1997, pp. 224–6; Wood 1992b, pp. 38, 42–3 (begun by Van Dyck in Antwerp and the portraits added much later); S. J. Barnes in Wheelock, Barnes & Held 1990, pp. 124–6, no. 17; Jaffé 1990. At about the same time Van Dyck made another scene of Venus and Adonis, but one in which Venus tries to stop Adonis from going hunting. RKD, no. 13643: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/13643 (July 19, 2019); De Poorter 2004, pp. 85–6, no. I.85. This is probably not a portrait historié.

28 https://www.rct.uk/collection/400118/portrait-of-a-woman (July 19, 2019). See also Van Beneden 2015, p. 13, fig. 3. As the picture was acquired by George IV in 1818 from the Lunden family, it was suggested that this lady was a member of the Lunden or the connected Fourment family (Elizabeth Fourment, sister of Rubens’s wife Hélène, born in 1606 (?)). The picture has on the verso a succinct oil sketch of the 1630s, which suggests that the portrait remained in Rubens’s studio.

29 Joconde (14 May 2014); Ducos 2011, p. 240, no. P.A.54 (c. 1612?).

30 RKD, no. 5525: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/5525 (July 23, 2019); see also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.5319 (July 19, 2019); in the Amsterdam Museum the inv. no. is SA–8295; see Bergvelt, Filedt Kok & Middelkoop 2004, p. 67, pl. 5 (Middelkoop note), 171, no. 149 (A. Pollmer), 204, no. 251 (E. Bergvelt); Huemer 1977, pp. 104–5, no. 3, fig. 45.

31 RKD, no. 184755: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/184755 (July 20, 2019); Lurie 1995, pp. 92–3, no. 55 (and 199–200, in Hebrew); Jaffé 1989, p. 285, no. 788; Huemer 1977, p. 182, no. 49.

32 RKD, no. 257791: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/257791 (Aug. 20, 2020); not mentioned in Huemer 1977, pp. 110–13, under no. 6 (the Dulwich picture) and 6a (the Vienna drawing).

33 RKD, no. 288806: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/288806 (Aug. 21, 2019).

34 See note 1 above.

35 Huemer 1977, p. 112. In the Burchard material in the Rubenianum there are also X-rays of the reverse. They were sent by Peter Murray to the Rubenianum. According to Burchard (RUB LB no. 1424 file) they are Entwürfe zu Hercules und Achelous und andere Figuren. Sicher von Rubens eigener Hand (studies for Hercules and Achelous and other figures. Certainly by Rubens himself). According to Sophie Plender, conservator, the drawing on the back is not considered to be by Rubens.

36 Belkin & Healy 2004, p. 330.

37 De Clippel 2010, p. 151. Another problem is that Millar for instance thinks the portraits were not painted by Van Dyck, but he doesn’t know a painter at the Jacobean court who could have made them: O. Millar in De Poorter 2004, p. 137. Wood 1992b is convinced that the Villiers/Manners couple is depicted in Related works, no. 3i.

38 Rubens was in Paris from February 1625; the public viewing of the complete cycle was on 27 May of that year: Saward 1981, p. 6.

39 There was an equestrian portrait, burnt at Osterley Park in 1949; for the rediscovered modello in Texas see Held 1957; Held 1980, i, pp. 393–5, no. 292, ii, pl. 294, col. pl. 11, and Sutton & Wieseman 2004, pp. 142–6, no. 15. Of the Apotheosis of Buckingham there is a modello in the NG, London (NG187), see RKD, no. 197429: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197429 (July 23, 2019); see also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-the-apotheosis-of-the-duke-of-buckingham (Jan. 25, 2021). According to that website the modello was made before 1625; but according to Martin (1970, p. 149) it was painted between 1625 and 1627. See also Held 1980, i, pp. 390–93, ii, pl. 293 (c. 1625).

40 Muller 2004, pp. 62–3; Muller 1989, pp. 82–7.

41 Jaffé 1990, p. 699.

42 Huemer 1977 (pp. 110–13, no. 6 and 6a) is not quite sure; Wood (1992a, p. 827, no. 65.2) is also doubtful; according to Laing (1999, p. 549) she is a French lady; Merle du Bourg (2004, p. 62) also thinks she is not Katherine Manners.

43 Comments by Bianca du Mortier, Nov. 2014.

44 For instance H. Vlieghe in Mai & Vlieghe 1992, p. 407.

45 Katherine Manners is shown wearing a miniature portrait of her deceased husband in Related works, nos 3b–d.

46 Email from Sophie van Gulik to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 22 May 2014 (DPG143 file); for mourning dress and jewellery see also Taylor 1983.