Peter Paul Rubens DPG131

DPG131 – Hagar in the Desert

1630–32; oak panel, 72 x 72.7 cm

PROVENANCE

?Augustin de Steenhaut sale, Brussels, 22 May 1758 (Lugt 1007), lot 1, De Vlucht van Hagar met haar Kindt in de Woestein, door P. P. Rubbens; 2 voet 6 duim by 2 voet 7 duim (The Flight of Hagar with her Child in the Desert, by P. P. Rubbens; 2 ft 6 in. x 2 ft 7 in. (c. 76.2 x 78.7 cm), on panel; 440 florins, 39l);1 ?Humbert Guillaume Laurent Borremans sale, Brussels, Loose, 5 June 1781 (Lugt 3278), lot 1 (‘A Landscape, in which is introduced the subject of Hagar and Ishmael’; 2 pieds 3 pouces x 2 pieds 2½ pouces (c. 68.6 x 67.3 cm), on panel); 790 florins;2 ?Dubois sale, Paris, Lebrun, 12 March 1782 (Lugt 3386), lot 13; bt Nicolas Lerouge for 4,999 livres 19 sols; 3 Insurance 1804, no. 58 (‘A Young Lady – Rubens; £150’); Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 16, no. 142 (‘Upper-Room – East side of passage / no. 5, Portrait: full length, one of Rubens wives: as Hagar – P[anel] Rubens’; 3'2" x 3'2").

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 9, no. 141 (‘SECOND ROOM – North side; Portrait of a Lady; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 383, no. 141;4 Cat. 1820, p. 9, no. 141; not in Patmore 1824a, 1824b;5 Cat. 1830, no. 182 (Rubens; Sketch); Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 253, no. 857, 60 gs;6 Jameson 1842, ii, p. 472, no. 182;7 Waagen 1854, ii, p. 342;8 Jameson 1850, p. 219;9 Denning 1858, no. 182;10 Denning 1859, no. 182;11 Blanc 1857–8, ii, p. 66;12 Lavice 1867, p. 181 (Rubens no. 7);13 Sparkes 1876, p. 152, no. 182 (Mary Magdalene); Richter & Sparkes 1880, pp. 141–2, no. 159 (Helen Fourment);14 Rooses 1886–92, i (1886), pp. 126–7 (engraving by F. De Roy),15 ii (1888), p. 323, no. 471 (St Magdalen in a landscape; Hélène Fourment; c. 1635);16 Richter & Sparkes 1892, pp. 33–4, no. 131; Rooses 1903, pp. 499 (fig.; Hélène Fourment as Magdalen), 590 (of lesser importance); Richter & Sparkes 1905, pp. 33–4, no. 131; Dillon 1909, p. 215 (‘Helen’ Fourment as the Magdalen in a Landscape); Cook 1914, pp. 77–8, no. 131; Glück 1920–21, p. 96 (note 2; Magdalen, not Hélène Fourment);17 Oldenbourg 1921, pp. 360, 470 (c. 1635; probably Hélène Fourment; not an expiatory Magdalen); Oldenbourg 1922, pp. 145–7 (fig. 84; Hélène Fourment);18 Cook 1926, pp. 73–4, no. 131 (‘simply a portrait of the painter’s second wife – a living incarnation of his feminine type of beauty’); Glück 1933a, p. 150 (note 57: Magdalen; not Hélène Fourment), p. 389 (note by L. Burchard: not Helene Fourment);19 Hennus 1936, pp. 162, 170;20 Van Puyvelde 1937, pp. 22–3 (fig.; Rubens, Hélène Fourment; De l’extrême fin de la vie de l’artiste (from the very end of the artist’s life)); Evers 1943, pp. 412, 506 (note 430);21 Grossmann 1948, pp. 54–5 (fig. 39; Rubens, Hagar); Cat. 1953, p. 35, no. 131 (Rubens, Hagar in the Wilderness); Paintings 1954, pp. 20–21, [60]; Gerson & Ter Kuile 1960, p. 106 (Hagar/Hélène Fourment), 189 (note 145); Klessmann 1965, p. 558, fig. 9 (Hagar/Hélène Fourment); Murray 1980a, p. 113 (Hagar in the Desert); Murray 1980b, p. 25; Lecaldano 1980, ii, p. 162, no. 1006 (c. 1635); Bodart 1985, p. 192, no. 757; Foucart 1987, p. 90 (fig.), under no. R.F. 1985–24 (Related works, no. 4); D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 56–8, no. 11; Jaffé 1989, p. 328, no. 1052 (c. 1630–32); Ingamells 1989, pp. 206–7 (note 6), under no. P442 (Related works, no. 8); Sutton 1993, p. 41 (fig. 35; Hélène Fourment); Beresford 1998, p. 209; Gockel 1998, p. 59 (fig. 2); Gockel 1999, p. 61, fig. 59; Sutton & Wieseman 2004, p. 206, under no. 28 (Related works, no. 5a); Van Hout 2014, pp. 302–4, no. 136; Tyers 2014, pp. 22–4; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 196–8, 213–14; Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 470–71, under no. R7 (Related works, no. 4); Büttner 2019, p. 84 (under no. 1), 93 (note 54), fig. 12; RKD, no. 27547: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27547 (July 18, 2019).

EXHIBITIONS

London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 41 (L. Burchard: Hagar in the wilderness, c. 1630–32);22 London 1950–51, p. 97, no. 225; London 1953–4, p. 65, no. 193; Japan 1999, p. 168, no. 26 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 140–41, no. 42 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Lille 2004, pp. 265–6, no. 149 (H. Vlieghe; c. 1630–32); Van Hout 2004c;23 Vienna 2004, pp. 458–60, no. 121 (H. Widauer); Brussels/London 2014–15, pp. 302–4, no. 136.24

TECHNICAL NOTES

Three-member horizontally joined Netherlandish oak panel with a gentle convex warp. The back of the panel is cradled, with nine horizontal fixed bars and nine slats, which no longer move. The edges have been modified, indicating that the panel has been cut down on all sides. Dendrochronology indicates that the panel derived from trees felled after 1620. There are remnants of two figures – in the sky an angel and at the bottom of the tree to the left a child – visible in ordinary light and under infrared light [1]. There is a 20 cm scratch down the back of Hagar’s dress with brittle blisters at the top, and a diagonal scratch below her proper right shin; the old restoration of these scratches now appears slightly dark. Three fairly small cracks can be seen at the right panel edge in the hill and there is some raised craquelure and old paint loss in the nearby sky, towards the top right corner. The hill is very thinly painted and slightly abraded. No records of previous treatments exist for this painting.

RELATED WORKS

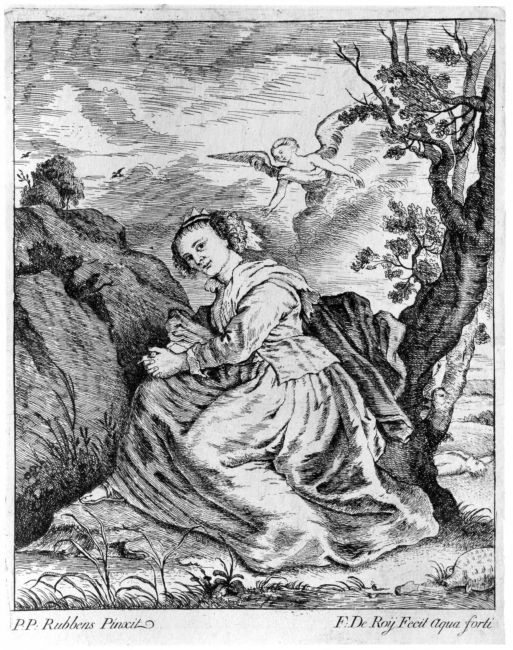

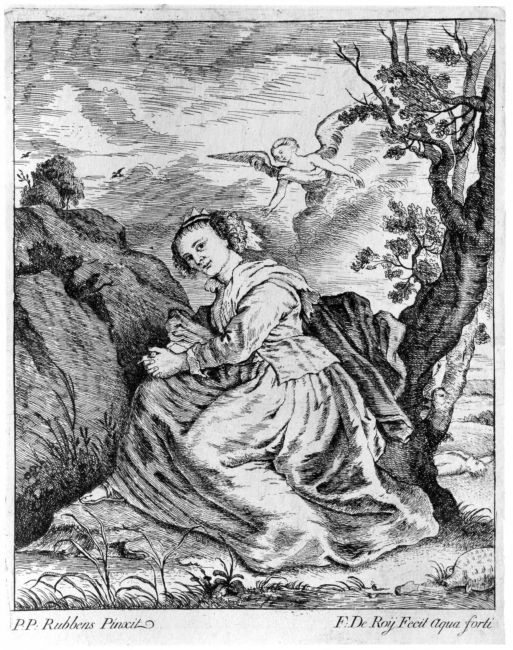

1) Copy (in reverse): Frans de Roy, Hagar with her Son in the Wilderness, c. 1758, inscriptions P.P. Rubbens Pinxit and F.DeRoij Fecit Aqua forti, etching, 272 x 215 mm (image). Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België, Brussels, S.I 27821 [2].25

Similar young women

2a) Study for 2c: Peter Paul Rubens, Seated Young Woman with Raised Arms, c. 1630–34, black and red chalk, with heightening in white, 423 x 500 mm. Staatliche Museen, Berlin, KdZ 4003.26

2b) Study for 2c: Peter Paul Rubens, Kneeling Young Woman, c. 1630–34, black and red chalk, with heightening in white, pen in brown, 508 x 458 mm. Département des arts graphiques, Louvre, Paris, 20.194 (recto).27

2c) Peter Paul Rubens, The Garden of Love, c. 1630–35, canvas, 199 x 286 cm. Prado, Madrid, P-1690 [3].28

3) Peter Paul Rubens, Study of a Young Woman (Hélène Fourment?), early 1630s, black, red and white chalk, 320 x 405 mm. Albertina, Vienna, 8255.29

4) Anonymous artist in the circle of Peter Paul Rubens, Allegory of Music, panel, 18.5 x 28 cm. Louvre, Paris, RF 1985–24.30

5a) Peter Paul Rubens, Study for a Portrait of a Family (Peter Paul Rubens and Hélène Fourment, with Nicolas and Clara Johanna Rubens), panel, 35.5 x 38.2 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art (John G. Johnson Collection), J622.31

5b) Peter Paul Rubens, Rest on the Flight into Egypt with Saints, 1632–5, panel, 87 x 125 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1640.32

5c) Peter Paul Rubens and Christoffel Jegher, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, c. 1633–5, pen and brown ink, retouched by Rubens with brush and black ink, heightened with white and garish white bodycolour, over preliminary drawing in black chalk, on cream-coloured paper, 474 x 615 mm. Fundacja im. Raczyńskich, Museum Narodowe, Poznań, Fr. 396.33

5d) Christoffel Jegher after Peter Paul Rubens, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, inscriptions, 1633–6, chiaroscuro woodcut: one line block and one tone block, 466 x 604 mm. BM, London, 1917,1208.559 [4].34

Other scenes with Hagar

6a) Jan Harmensz. Muller after Harmen Jansz. Muller, Hagar and the Angel, inscriptions, c. 1591, engraving, 175 x 210 mm. BM, London, 1853,0312.1.35

6b) Herman van Swanevelt, The Angel consoling Hagar (from a series of four plates), H. Swanevelt Fe Rom. and other inscriptions, etching, sheet 125 (trimmed) x 202 mm. BM, London, S.2219.36

6c) Peter Paul Rubens, The Expulsion of Hagar, c. 1615–18, panel, 63 x 76 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, GE-475.37

6d) Peter Paul Rubens, The Expulsion of Hagar, 1618, panel, 71 x 102 cm. Collection of the Duke of Westminster, Eaton Hall.38

Copies

7a) Jeremias Wildens inventory: Op de Schilders Camer (In the painter’s room), Antwerp, 30 Dec. 1653, no. 286, Een Aga naer Rubbens (A Hagar after Rubens).39

7b) Copy of DPG131: Hagar in the Wilderness, canvas, 24½ x 29¾ in. (c. 62.2 x 75.6 cm). Seena and Arnold Davis collection, Scarsdale, N.Y., in 1980.40

7c) Copy: ?Thomas Gainsborough, Hélène Fourment, canvas, 50.5 x 60.9 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Bonhams sale, 28 March 1974, lot 60; Marshall 1973, pp. 6–8, lot 6).41

Distant relative

8) Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Le Malheur imprévu (The Broken Mirror), c. 1762–3, canvas, 56 x 45.6 cm. The Wallace Collection, London, P442.42

Lent to the RA to be copied in 1902, 1922 and 1930.

DPG131

Peter Paul Rubens

Hagar in the wilderness after her expulsion (Genesis 21: 9-19), 1630-1632

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG131

1

Infrared photo pf DPG131 with angel visible.

2

Frans de Roij after Peter Paul Rubens

Hagar in the wilderness after her expulsion (Genesis 21: 9-19), c. 1758

Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België, inv./cat.nr. Printroom, S.I 27821

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Garden of love, c. 1630-1635

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. 1690

4

Christoffel Jegher after Peter Paul Rubens

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1917,1208.559

DPG131 was originally larger, if we are to believe an 18th-century print (Related works, no. 1) [2]. That etching, by the otherwise almost unknown Frans de Roy, shows (in reverse) more of the composition at the top: there seem to be c. 15–20 cm missing, with part of the sky and of the tree. The print is generally dated c. 1758.43 Why the picture was reduced in size is not clear. The angel in the sky behind Hagar and the figure of Ishmael prostrate on the far left, half hidden behind the tree, visible in De Roy’s print, were painted out some time later. The figure of the angel is still visible, especially in infrared photographs [1]. The angel and infant were perhaps painted out just before the Dubois sale in 1782, where the painting is described without mentioning those figures (see Provenance), but that could have happened earlier under a previous owner. Cleaning in the 1940s brought traces of these figures back to the surface. The question remains whether they were originally painted by Rubens or were later additions (see below). The appearance of the angel and Ishmael settled more than a century of debate when the picture had been called a Portrait of a Lady (the early DPG catalogues),44 Mary Magdalen (in Smith, Waagen, Jameson, Denning, Lavice, Sparkes, and Glück in 1933) or a Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Hélène Fourment (the DPG catalogues since 1880, Oldenbourg, and Van Puyvelde). It does seem likely, however, that the painting is both a biblical scene and a portrait of an actual woman, perhaps the artist’s wife, the sort of picture that is called a portrait historié (see under DPG285). Indeed, in the inventory of the Bourgeois collection made by Britton in 1813 it is given the title ‘one of Rubens wives: as Hagar’. In 1888 Rooses suggested that it was a combination of Mary Magdalen and Hélène Fourment. The dress and hairstyle are reminiscent of those of the women in Rubens’s famous Garden of Love in the Prado (Related works, no. 2c) [3], for which there are several preparatory drawings of which the sitter is no longer identified as Hélène Fourment (Related works, nos 2a–b). The sketchiness of DPG131 led Widauer to call it, wrongly, unvollendet (unfinished).45

Rubens developed the seated young lady looking at us freely as a motif in the 1630s. According to Wieseman the figure started as Hélène Fourment holding her newborn daughter in a sketch now in Philadelphia (Related works, no. 5a) and then changed into a Madonna, who holds her Son on the Rest on the Flight into Egypt in the Prado, and in the later prints after that picture by Rubens and Christoffel Jegher (Related works, nos 5b–d) [4].46 The posture of the Madonna is upright, like that of Hélène in the earlier sketch. She became a richly dressed lady in the centre of the Garden of Love (Related works, no. 2c) [3]. There she is still upright, but without the baby. In DPG131 she has the same hairstyle, but her posture has changed from upright to leaning forward, and the sparkling yellow dress with almost bare breasts in the Garden of Love is here a combination of pastel colours (green for the skirt and blue for the jacket), with a white veil which very decently covers her. In the Allegory of Music in the Louvre, if that is indeed painted by Rubens, she is shown in reverse posture, with a lyre in her hands (Related works, no. 4).

The question is whether the lady in DPG131 is indeed Hagar. The story of Hagar comes from Genesis 16–21. She was an Egyptian servant belonging to Sarah, who, unable to have children, gave her as a gift to her husband Abraham so that he might have heirs. Treated badly by Sarah, the pregnant Hagar fled from Abraham into the wilderness; an angel of the Lord found her by a fountain and commanded her to return, upon which she was delivered of a son, who she named Ishmael. Later the aged Sarah gave birth to Isaac, leading Hagar and Ishmael to be banished to the desert. When Hagar despaired that her son would die of thirst an angel appeared and pointed to a spring, announcing, ‘Arise, lift up the lad, and hold him in thine hand; for I will make him a great nation. And God opened her eyes, and she saw a well of water; and she went, and filled the bottle with water, and gave the lad drink’ (Genesis 21). The empty vessel lies on the ground to the left in DPG131. Galatians 4:22–31 explains that Hagar was a symbol of the old covenant and Sarah of the new. In any case, Hagar fled twice into the wilderness, the first time pregnant and the second time with her son.

The scene in DPG131 is not a regular Hagar in the Desert. In the 16th and 17th century Hagar’s second flight into the wilderness would usually have been depicted; consequently the angel would have been prominently present, showing Hagar the water that would save her and her son: see for instance the engraving by Jan Harmensz. Muller (1571–1628; Related works, no. 6a). Ishmael need not be present, but the bottle is necessary, as in the etching by Herman van Swanevelt (c. 1603–55; Related works, no. 6b). The figure in DPG131 is a young lady in contemporary dress, who does not look like a slave who is almost dying of thirst in the wilderness with her young son. The rich attire could indeed suggest a penitent Mary Magdalen, but in that case the saint would be shown differently, not looking at us freely as here. She is not crying, nor has she a red face, as Widauer says.47 The only things that could point to her being Hagar are the vessel and the fact that she is wringing her hands. But there still is the possibility that Ishmael and/or the angel were added later, after the picture had left Rubens’s studio, and then removed again.

Rubens had already painted two versions of an earlier part of the story in The Expulsion of Hagar, now in the Hermitage (c. 1615–18) and in the collection of the Duke of Westminster (1618; Related works, nos 6c, 6d), and claimed that the theme was new as a pictorial invention. In the Corpus Rubenianum volume the subject of the pregnant Hagar being dismissed from the house is characterized as a scene of ordinary life.48 It might be possible that in DPG131 Rubens depicted an unusual subject from the story of Hagar, as suggested by Elizabeth McGrath,49 namely the episode when Hagar was pregnant and in the wilderness for the first time, where she was found by an angel by a fountain. That would explain both the strange events surrounding Ishmael and the angel (added by somebody who wanted the more conventional subject from the Hagar story: the second time that Hagar was in the wilderness with her son) and Hagar’s healthy appearance as well as her beautiful dress (the pregnant Hagar herself, proudly, had chosen to flee the hostile house of Sarah and Abraham). Rubens has not depicted a mother worried about her son dying of thirst. The choice of the earlier episode with the pregnant Hagar would indeed be a new subject, and by portraying Hagar in contemporary clothing Rubens made the scene more relevant to his own time.

It seems that at least two versions of this picture were present in London around 1800. If the painting did indeed come to London soon after the sale in Paris in 1782, then Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88) would have been able to copy it before his death in 1788 (Related works, no. 7c). One can appreciate how the sketchiness and especially the way of rendering the satins would have appealed to the British master. The picture that was at auction in London in 1807 must have been another, since DPG131 was already in the Desenfans collection, according to the Insurance list of 1804.50

DPG131

Peter Paul Rubens

Hagar in the wilderness after her expulsion (Genesis 21: 9-19), 1630-1632

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG131

1

Infrared photo pf DPG131 with angel visible.

2

Frans de Roij after Peter Paul Rubens

Hagar in the wilderness after her expulsion (Genesis 21: 9-19), c. 1758

Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België, inv./cat.nr. Printroom, S.I 27821

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Garden of love, c. 1630-1635

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. 1690

4

Christoffel Jegher after Peter Paul Rubens

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1917,1208.559

Notes

1 Terwesten 1770, p. 195; Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 173, no. 604; not in GPID (11 July 2014).

2 Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 182, no. 634; Lugt online gives as description P.P. Rubbens; Un Paysage, dans lequel on voit Agar, ayant ses mains jointes, & accablée d’une grande tristesse: les Draperies sont supérieurement touchées; & l’on peut dire, que c’est un chef-d’œuvre de cet Artiste.’ On panel, haut. 2 pieds 3 pouces, larg. 2 pieds 2½ pouces. (A landscape in which one sees Hagar, with her hands clasped, & overwhelmed by a great sadness: the draperies are exceptionally well painted; & one can say that this is a masterpiece by that artist [NB: French dimensions, without the frame]. The difference in dimensions between 1758 and 1781 can be caused by whether or not the frame is included. Rooses (1886–92, v (1892), p. 311) links the print of De Roy (Related works, no. 1; Fig.) to the Borremans sale, while other authors and the Brussels Print Room link that print to the 1758 sale. See also note 25 below.

3 Not in Lugt online; GPID (24 Aug. 2020): P. P. Rubens; Une femme assise les bras allongés & les mains jointes, & posées sur le genou gauche; elle est vue de trois quarts, & le regard tourné vers le spectateur. Elle est vêtue d'une juste-au-corps de satin gris, & d'une jupe de satin verd. Elle a le sein couvert d'un voile léger, & tient envore [encore] dans son bras gauche une portion de son manteau violet qui tombe derriere elle; l'expression que l’on remarque dans la tête, l’action générale de la figure & une bouteille vuidée [vidée] placée sur le devant, feroient croire que c’est Agar dans le désert. Ce Tableau, rare & supérieur, est sorti du pinceau de Rubens dans sa plus grande force. Nous ne nous étendrons pas sur la difficulté de rencontrer de vrais Tableaux de ce Maître, nous offrons celui-ci comme un de ses plus agréable pour les Cabinets. Hauteur 26 pouces, largeur 23 pouces. B. (P. P. Rubens; a woman seated with her arms stretched out & her hands clasped and resting on her left knee; she is seen in three-quarter view, looking at the spectator. She is wearing a grey satin jacket and a green satin skirt. Her breast is covered with a light veil, and in her left arm she holds part of her violet mantle that falls behind her; the expression that one sees in her face, the general action of the figure, and an empty bottle in the foreground suggest that this is Hagar in the wilderness. This painting, rare and of high quality, is from the hand of Rubens at his strongest. We will not expand on the difficulty of finding genuine pictures by that master; we offer this as one of his most agreeable for a collector. 26 x 23 in. [Austrian Netherlandish dim.; c. 70.4 x 62.3 cm]. On panel.) NB: according to D’Hulst & Vandenven (1989, p. 56), Vlieghe (Rubens 2004, p. 265) and GPID (19 Oct. 2020), the picture then went to De Laborde-Méréville in Paris (?François-Louis-Joseph de Laborde-Méréville sale, Paris, 14 June 1784 (Lugt 3744), presumably unsold (for his collections see Boyer 1967)); his sale, Christie’s, 7 March 1801 (Lugt 6210), lot 49 (‘Rubens – His own Wife, a fine Sketch’); bt Edward Coxe for £36.15 (a note in the Coxe sale catalogue has the figure as ‘35½ Gs’); London, Edward Coxe, 24 April 1807 (Lugt 7229), lot 54 (‘The story of Hagar, in a single Figure, and that Figure taken from the Person of Helena Forman, Rubens’ Wife; beautifully managed with a silvery tone of color, and is transparency itself – a most capital Performance, evidently the entire work of Rubens, was purchased at Mr. La Borde’s Sale’); bt George Douglas, 16th Earl of Morton, for £47.5). However this is not very plausible, since DPG131 already figures in Desenfans’ 1804 Insurance list. Moreover, the picture acquired by the Earl of Morton in 1807 was a most ‘capital’ performance, which cannot be said of DPG131. And how did Bourgeois purchase it from the Earl? That was probably a different picture.

4 ‘SIR P. P. RUBENS, Portrait of a Lady sitting under a Tree. In Flemish drapery of changeable silk, with sandals on her naked feet; her hands are clasped on her knees in an attitude of despair; she may be, perhaps, a Flemish Dido. It is, however, beautifully painted.’

5 According to D’Hulst & Vandenven (1989, p. 56) Patmore mentions it on pp. 208–9, no. 228, but the Venetian lady mentioned is in DPG198 (after Titian).

6 ‘A Female, apparently about twenty-five years of age, seated in a solitary Landscape […]; the countenance and position appear to denote abandonment of the world, and resignation to the secluded life of a Magdalen. […] An admirable study for a large picture. […] Now in the Dulwich Gallery.’ The subject of Hagar and Ishmael is mentioned by Smith on p. 173, no. 604 (the Steenhaut sale in 1758) and on p. 182, no. 634 (the Borremans sale in 1781); for both see under Provenance.

7 ‘A Woman seated in bluish drapery, with clasped hands. – Much less than life. Intended, I am afraid, for Mary Magdalen in the desert. It is a spirited sketch in the manner of Rubens.’

8 ‘The Magdalen in a Landscape, clasping her hands. A very spirited sketch. (No. 182.)’

9 ‘In a sketch by Rubens in the Dulwich Gallery, she is seated in a forest solitude, still arrayed in her wordly finery, blue satin, pearls &c., and wringing her hands with an expression of the bitterest grief. The treatment, as usual with him, is coarse, but effective.’

10 ‘Smith’s Cat: Rais: 857; A combination of beautiful colour and painted with the greatest dexterity. S.P.D. This is meant for Mary Magdalene. It is probably a Sketch of the picture mentioned by Smith. no: 290. Engraved by Vosterman [sic].’ The Vorsterman engraving (not in BM) is completely different; see Teylers Museum, Haarlem, KG 17448: https://www.teylersmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/kunst/kg-17448-st-magdalena-met-haar-voeten-op-een-juwelenkistje (July 26, 2019).

11 ‘Mary Magdalene. A Sketch; This is numbered 857 in Smith. It presents a combination of beautiful colours and is painted with the greatest dexterity.’

12 499 Dubois Sale, 1782 (see Provenance): Rubens; Une femme assise les bras allongés, les mains jointes, posées sur le genou gauche (Agar?) 26 p. de haut sur 23, bois. 4.999 liv. 19 s.’ (Rubens; a seated woman with her arms extended, hands clasped, resting on her left knee (Hagar?) 26 in. by 23 [c. 70.4 x 62.3 cm], on panel. 4,999 livres, 19 sols).

13 Madeleine en robe de soie verte, mains jointes et nous regardant. Portrait de la Fermann peu achevé. (Magdalen in a green silk dress, her hands clasped, and looking at us. Portrait of ‘la Fourment’, not very finished.)

14 ‘Portrait of Helen Fourment, sitting in front of a pool. […] Painted à la prima, in light colours, of extraordinary glowing power. […] Formerly described as representing Mary Magdalen […]’

15 A en juger par la gravure, la composition ne saurait être attribuée à Rubens (Judging by the engraving, the composition could not not be attributed to Rubens). The picture was sold in 1758 in Brussels (Coll. M. de Steenhault 2 pieds 6 pouces x 2 pieds 7 pouces).

16 C’est une peinture légèrement brossée, d’un ton très clair. Malgré cela, le tableau est assez mediocre; il manque d’invention et d’expression caractéristique. Il y a là une femme, bien nourrie, pleine de force et de santé, plutôt qu’une pénitente contrite. Le travail est de la main du maître et date de 1635 environ. (The painting is sketchy, and very light in tone. Despite that, the picture is fairly mediocre; it lacks invention and characterful expression. It shows a woman, well fed, full of strength and health, rather than a contrite penitent. It is by the hand of the master and dates from around 1635.)

17 auf dem reizvollen, offenbar zur Zeit des Liebesgarten entstandenen Bilde der heiligen Magdalena in der Galerie zu Dulwich. Mit Unrecht hat hier Rooses die Züge Helenens zu erkennen geglaubt (on the charming picture with St Magdalen in Dulwich, clearly made in the same period as the Garden of Love [Prado]. Rooses incorrectly saw here the features of Helena [Fourment]).

18 p. 146 (note 1): Schon früher scheint das Bild falsch gedeutet worden zu sein, da es im 18. Jahrhundert mit Einfügung eines Ismael als ‘Hagar in der Wüste’ gestochen wurde. (It seems that this image was already incorrectly interpreted earlier, since in the 18th century it was engraved with the addition of an Ismael as ‘Hagar in the Wilderness’); p. 147: wo sie vor dem strahlenden Gemälde, das zu den hinreißendste Improvisationen von Rubens’ Pinsel gehört, unauslöschliche Eindrücke empfing (where one received lasting impressions before the radiant picture, one of the most captivating improvizations of Rubens’s brush).

19 ist Oldenbourg der Ansicht von Rooses beigetreten, wonach in der “Schönen Büszerin” der Dulwich College-Galerie Helene Fourment zu erkennen sei. Wir möchten demgegenüber mit Gustav Glück […] daran festhalten, dasz kaum eine Ähnlichkeit met den Zügen Helenes besteht.’ (Oldenbourg agrees with Rooses, that the ‘Beautiful Penitent’ of the Dulwich College Gallery looks like Helene Fourment. We, on the contrary, would like to maintain the opinion that there are hardly any similarities with the physiognomy of Helene.)

20 van Rubens een zeer bijzondere Hélène Fourment, lang als een boetvaardige Magdalena bekend (by Rubens a very special Hélène Fourment, long known as a peninent Magdalen).

21 Evers had not seen DPG131.

22 ‘The figures of Ishmael and the angel were probably painted out by Dubois, for in his sale it is described as Une femme assise, les bras allongés, les mains jointes, posées sur le genou gauche (Agar?). The title “Hagar” reappears in the Bourgeois inventory of 1813, and was only changed in the Dulwich catalogue, where till 1880 it was described as “Mary Magdalene.” The recent cleaning revealed traces of the angel in the sky under repainting. Painted c. 1630–32, about the same time as the “Garden of Love” in Madrid.’

23 ‘the elegant and worldly Hagar in the wilderness […] might have been painted for rich burghers or for display in a church.’

24 Das Bild in Dulwich zeigt jenen Moment, als Hagar angesichts der Wassernot zu weinen beginnt […] Ihr Gesicht ist gerötet […] doch sind kaum Tränen erkennbar; im Gegenteil, der herausfordernde Blick und der Umstand, dass sie sich von dem am Himmel erscheinenden Engel vollkommen unbeeindruckt gibt, weist auf Rubens’ Absicht hin, hier eher ein Porträtgemälde schaffen zu wollen. (The picture in Dulwich shows the moment when Hagar starts to cry because of the lack of water […] her face is flushed […] but tears are hardly visible; on the contrary, the challenging look and the fact that she is completely unimpressed by the angel points to Rubens’s intention, to paint a portrait [rather than a scene from the Old Testament].)

25 RKD, no. 244997: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/244997 (Aug. 18, 2019); Voorhelm Schneevoogt 1873, pp. 4–5, no. 29: Agar avec son fils dans le désert. Sans titre. F. de Roy fecit aqua forte. Agar est habillée de vêtements du temps de Rubens. 10 p. 2 l. de haut. 8 p. de large. B [Brussels] Le tableau se trouvait en 1758 dans la collection de M. de Steenhault, à Bruxelles.’ (Hagar with her son in the wilderness. No title. F. de Roy made this etching. Hagar is dressed in clothes of the time of Rubens. [dimensions] [in the Print Room] Brussels. In 1758 the picture was in the collection of Mr. de Steenhault in Brussels.) Rooses 1886–92, v (1892), p. 311, links this print to the Borremans sale in 1781, while other authors and the Brussels Print Room link it to the 1758 sale; see also note 2 above. Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 196, fig. 22, under DPG131; D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 56–7, fig. 25 (this print is said to be an etching on p. 56 and an engraving on p. 57); according to Widauer 2004b, p. 458, it is an engraving; T. Barringer (in Van Hout 2014, p. 305) also says engraving. According to Joris Van Grieken of the Brussels Print Room it is an etching: email from Joris Van Grieken to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 9 April 2015 (DPG131 file).

26 Büttner 2019, pp. 107–9, no. 1g, fig. 42; Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 256–60, no. 90; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 426–30, no. 111; Mielke & Winner 1977, pp. 100–102, no. 36.

27 Büttner 2019, pp. 102–4, no. 1d, fig. 33; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 428–30, no. 114; Sérullaz 1978, pp. 44, 46, no. 26.

28 RKD, no. 270906: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/270906 (Aug. 18, 2019); see also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/el-jardin-del-amor/ (July 26, 2019); Büttner 2019, pp. 64–96, no. 1, figs 1–3, 6, 8, 11, 13, 19, 20, 23, 31, 36, 43, 51, 62, 71, 73; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 426–30, no. 110; Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 982–7, no. 1690.

29 RKD, no. 259469: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/259469 (Aug. 18, 2019); Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 268–70, no. 96; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 444–6, no. 117 (recto); Mitsch 1977, pp. 124–5, no. 53.

30 RKD, no. 218051: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/218051 (Aug. 18, 2019); Büttner 2018a, i, pp. 470–71, no. R7 (under ‘Questionable and Rejected Attributions’), ii, fig. 314; Foucart 1987, pp. 90–92, no. R.F. 1985–24; not in Held 1980.

31 RKD, no. 23611: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23611 (Aug. 18, 2019); see also https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/102466.html?mulR=23107936|9 (July 26, 2019); Van Beneden 2015, pp. 214–6, no. 31; Sutton & Wieseman 2004, pp. 204–7, no. 28 (M. E. Wieseman); Scott, Dugan & Paschetto 1994, p. 92; Vlieghe 1987b, pp. 94 (under no. 98), 169–70, no. 140; Held 1980, i, pp. 399–401, no. 296, ii, pl. 296.

32 RKD, no. 22590: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22590 (Aug. 18, 2019); see also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/descanso-en-la-huida-a-egipto-con-santos/ (July 26, 2019); Van Beneden 2015, p. 214, no. 31a; Logan & Plomp 2004c, p. 267 (fig. 143); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 872–5, no. 1640; Jaffé 1989, p. 333, no. 1086; Adler 1982, pp. 143–6, no. 43; fig. 120.

33 RKD, no. 236943: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/236943 (Aug. 19, 2019); Büttner 2019, p. 127, under no. 2c, fig. 58; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 197–8, fig. 26, under DPG131; Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 265–7, no. 95 (recto); Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 461–4, no. 122.

34 RKD, no. 22613: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22613 (Aug. 19, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1917-1208-559 (Aug. 2, 2020); Curator's comments: ‘The same composition attributed to Rubens’s studio (but with figures of St George and other saints added) is in the NG, London, NG67.’ Büttner 2019, pp. 115–20, no. 2 (figs 49, 54), where earlier states of the print are discussed; the print is here dated c. 1633–5.

35 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1853-0312-1 (Aug. 2, 2020); Curator’s comments: ‘Preparatory drawing in the Cabinet des Dessins, Musée du Louvre, Paris’; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 198, fig. 25, under DPG131.

36 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Sheepshanks-2219 (Aug. 2, 2020); Curator’s comments: ‘BM has a complete set of the series. This is third state; for another impression see 2006,U.439. For earlier states see S.2218 and F,2.212.’

37 RKD, no. 27543: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27543 (Oct. 19, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 198, fig. 24, under DPG131; D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 51–3, no. 9; Jaffé 1989, p. 240, under no. 492 (studio of Rubens).

38 RKD, no. 27546: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27546 (Oct. 19, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 198, under DPG131; D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 53–6, no. 10; Jaffé 1989, p. 240, no. 492.

39 Denucé 1932, p. 161.

40 RKD, no. 244995: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/244995 (Aug. 24, 2020). Letter from Seena and Arnold Davis to Giles Waterfield, 13 May 1980 (DPG131 file).

41 RKD, no. 244994: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/244994 (Aug. 24, 2020); Gockel 1998, p. 59; Gockel 1999, p. 61 (note 14); Marshall 1973, pp. 6–8, no. 6; this exhibition catalogue announces a sale at Sotheby’s, but that does not seem to have taken place: the picture was sold at Bonhams.

42 RKD, no. 198566: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/198566 (Oct. 19, 2020); see also https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultDetailView/result.tab.link&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SelementList&sp=0&sp=0&sp=999&sp=SdetailView&sp=0&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F&sp=SdetailBlockKey&sp=3 (July 29, 2019); Michel 2010, pp. 270–71 (fig. 91); Ingamells 1989, pp. 205–7, no. P442. When Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805) made this picture DPG131 was not in Paris; that was only in 1781–2 (if the provenance is right). It is possible that Greuze saw the print by Frans de Roy, if indeed that was made c. 1758.

43 If it is related to the sale of that year, see notes 2 and 25 above. De Roy was also an auctioneer in Brussels in the years 1768–94: note in RUB, LB no. 77/2 file).

44 The Portrait of a Venetian Lady, mentioned in the Corpus volume as being found in Patmore 1824b (D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, p. 56, under Literature), was a different picture (DPG198, now after Titian, but in 1824 thought to be by Rubens).

45 H. Widauer in Schröder & Widauer 2004, p. 460.

46 M. E. Wieseman in Sutton & Wieseman 2004, p. 206.

47 H. Widauer in Schröder & Widauer 2004, p. 460: Ihr Gesicht ist gerötet (her face is flushed); see also note 24 above.

48 Rubens in a letter in Italian to Dudley Carleton of 20 May 1618 uses the words vero originale for the picture now in the Westminster collection. These words are interpreted differently – as entirely by Rubens’s hand, or as a truly original subject; the Corpus authors chose the latter meaning. Rubens adds: ‘It is done on a panel because small things are more successful on wood than on canvas.’ D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 54, 55 (note 7).

49 Suggested in conversation by Elizabeth McGrath in 2015, as cited in Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 196, 214 (note 182).

50 See note 3 above.