Peter Paul Rubens DPG40AB

DPG40A – SS. Amandus and Walburga

DPG40B – SS. Eligius and Catherine of Alexandria

c. 1610; oak panel, 66.6 x 25 cm each.1

NB: until c. 1947 they were joined (see Technical Notes).

DPG40A

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Amandus and Walburga, c. 1610

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG40A

DPG40B

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Eloy (Eligius) and Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1610

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG40B

PROVENANCE

2; ?Jacques de Roore (1686–1747) sale, The Hague, 4 Sept. 1747 (Lugt 672), lot 56, fl. 102, bt Van Spangen;3 not Desenfans sale, 1786;4 Insurance 1804, no. 101 (‘Saints – Rubens; £80’); Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 24, no. 247 (‘Drawing Room / no. 35, A group – priests & a full length of a Queen sketch – P[anel] Rubens’; 3' x 2'6").

REFERENCES

Hoet 1752, ii, p. 204, no. 56;5 Cat. 1817, p. 9, no. 164 (‘SECOND ROOM – East side; An Historical Sketch; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 386, no. 164;6 Cat. 1820, p. 9, no. 164 (‘An Historical Sketch’); Cat. 1830, p. 6, no. 78; Jameson 1842, ii, pp. 454–5, no. 78;7 Denning 1858, no. 78 (‘Historical Sketch of Four Saints. It is a sketch for a larger Picture, which however does not seem to have been executed’); Denning 1859, no. 78; Lavice 1867, p. 181 (Rubens, no. 9);8 Sparkes 1876, pp. 149–50, no. 78 (Rubens; St Ambrose, St Gregory, St Catherine, & St Theresa); Richter & Sparkes 1880, pp. 144–5, no. 78 (‘painted in the style of Rubens by his scholars or imitators; the great slenderness of the figure and the monotonous colouring betray a later period than that of Rubens’); Rooses 1886–92, ii (1888), pp. 78–9, nos 278–9bis (Rubens; p. 73: St Eligius and St Walburga left; St Catherine and St Amand right); Richter & Sparkes 1892, pp. 9–10, no. 40 (School of Rubens); Rooses 1903, p. 135 (Rubens; SS. Eligius and Walburga left; SS. Catharina and Amandus right); Richter & Sparkes 1905, pp. 9–10, no. 40 (School of Rubens; St Gregory (?) and another saint left; St Catherine and St Ambrose (?) right); Cook 1914, p. 23, no. 40 (School of Rubens); Glück 1923, p. 174 (Rubens); Cook 1926, p. 22, no. 40; Burchard 1926, p. 2, nos 11–13 (Rubens, sketch for St Paul’s altar with wings: Related works, no. 5b); Norris 1933, p. 230; Glück 1933a, i, pp. 72 (Rubens, SS. Eligius and Walburga left, Catharine and Amandus right), 382 (note by L. Burchard: Rubens); Grossmann 1948, pp. 48–9 (figs 34–5); Cat. 1953, p. 35, nos 40 and 40a (Rubens; St Amandus and St Walburga; St Catherine and St Eligius); Paintings 1954, pp. 17, [60]; Seilern 1955, p. 86, under no. 54, fig. 51 (Related works, no. 3); Grossmann 1957a, p. 6; Held 1959, i, p. 95, under no. 5; Wescher 1960, p. 35; Gerson & Ter Kuile 1960, p. 184 (note 45); Burchard & D’Hulst 1963, i, p. 100, under no. 59 (Related works, no. 3); Müller Hofstede 1967b, pp. 35, 38, 40 (fig. 3); Martin 1968a, pp. 145, under no. 26, 168, under no. 34; Martin 1969, pp. 41–3, fig. 13; Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), pp. 79, under no. 56a (Related works, no. 6a), 96–7, under no. 65 (Related works, no. 11), 106, under no. 71 (Related works, no. 7a); Liess 1977, pp. 105–6, notes 8–9;9 Glen 1977, p. 238; Mitsch 1977, p. 204, under no. 102 (Related works, no. 6d); Van Gelder 1978, p. 456; Murray 1980a, pp. 111–12, nos 40 and 40A (SS. Amandus and Walburga and SS. Catherine of Alexandria and Eligius; St Walburga ‘seems to have had no connection with Flanders’); Murray 1980b, p. 25; Held 1980, i, pp. 480, under no. 349 (Related works, no. 1a), 481–2, nos 350A, B (St Walburga ‘apparently had no connection with Flanders’), 545, under no. 398 (Related works, no. 5a); Lecaldano 1980, i, pp. 102–3, nos 106–7 (1610); Bodart 1985, p. 157, no. 112e; Braham 1988, p. 25, under no. 29 (Related works, no. 3); Jaffé 1989, p. 173, nos 132I and II 2–3 (c. 1610); Baudouin 1992a, pp. 72–6 (fig. 50); Goetghebeur, Guislain-Wittermann & Masschelein-Kleiner 1992, pp. 125, 141 (fig. 66); Heinen 1996, pp. 69–72, 117–18 , 129–30, 134 (notes 346–7), 235 (note 4), 235 (note 14), 267 (notes 258–9),10 269 (notes 290–91), 270 (note 303), 287 (note 87), 323 (notes 298–9), 324 (notes 309–11); Beresford 1998, pp. 206–7; Lawrence 1999, pp. 267–8, 271, 273 (and fig. 7), 274 (and fig. 8), 276, 279–80, 284 (fig. 17: the Dulwich modelli as inner wings) 285, 286 (fig. 19), 288, 291 (notes 12–14), 292 (note 43), 293 (note 43) 293 (notes 44 and 46), 295 (notes 113–14), 296 (note 128); Judson 2000, pp. 111–12, no. 21a, fig. 83, p. 113, pp. 115–16, no. 22a, fig. 84; Bellini & Gritsay 2007, p. 40 (figs 18, 19); Lepape 2009b, p. 64 (fig.; DPG40B); Gottwald 2011, pp. 68–9 (fig. 27), 198 (notes 403–5); Brosens 2011, pp. 235–6 (note 13); Tyers 2014, pp. 10–15; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 177–81, 212; RKD, no. 23346: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23346 (Sept. 19, 2018) and RKD, no. 23344: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23344 (Sept. 19, 2018).

EXHIBITIONS

London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 45a and b (L. Burchard; left, St Amandus and St Walburga; right, St Catherine and St Eligius); Rotterdam 1953–4, pp. 40–41, nos 8 and 9, pl. 10 (E. Haverkamp-Begemann); Bruges 1956, pp. 55–6, no. 71, fig. 54; London 1977, pp. 60–61, nos 55, 56 (J. Rowlands); Japan 1999, p. 166, nos 20–21 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 128–9, nos 35, 36 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Lille 2004, pp. 73–5, nos 31, 32 (H. Vlieghe); London 2005–6, pp. 118–19, nos 48, 49 (D. Jaffė); Madrid/Rotterdam 2018–19, pp. 76–79, nos 9, 10.

TECHNICAL NOTES

DPG40A: Single-member Netherlandish oak panel with vertical grain. Dendrochronology suggests that this tree was felled after c. 1577. Dowel marks in this panel line up with similar marks in DPG40B, indicating that the panels were once previously joined. There is a canvas strip along the verso left side, which also joined this to the other panel. The ground is white with a thin grey priming. There are some pentimenti, for example above St Walburga’s head. The panel has a gentle convex warp. There is an old split in the bottom centre and some small chips on the right side. The spandrel at the top left is abraded where the design was altered. The paint is generally well preserved.

DPG40B: Single-member eastern Baltic oak panel with vertical grain and slight convex warp. This is an unusual work where a Netherlandish and an eastern Baltic board were once combined to make one panel.11 Dendrochronology suggests that this tree was felled after 1593, with a usage date of between c. 1593 and c. 1625. There is an old retouched 24 cm split on the back starting at the bottom, and another to the left that is 9.5 cm long. There are remnants of canvas and glue down the right edge, where this panel was joined to DPG40A, and dowel marks on this edge line up with marks on the other panel. There is an area of fill and repaint in the top right-hand corner, which corresponds to the spandrel area in the top left of DPG40A. The paint mixtures contain mostly earth pigments, but there is vermilion in St Eligius’s gloves, the putto’s cloak and in some of the flesh tones. The paint is well preserved apart from the aforementioned cracks, although there is another less noticeable crack in St Catherine’s waist that is visible in UV. Previous recorded treatment: the two panels are thought to have been separated by Hell probably c. 1947 (see London/Leeds 1947, nos 45a and b); 1977, frame and backboard of both panels adapted, and a split in panel of DPG40A filled and retouched, British Museum; 1980, conserved, National Maritime Museum, C. Hampton.

RELATED WORKS

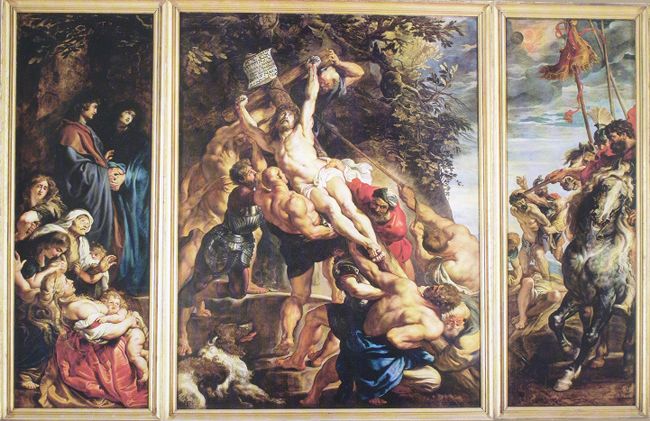

1a) (modello for 1b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Raising of the Cross (triptych), c. 1610, panel, centre piece 68 x 51 cm; wings 67 x 25 cm (each). Louvre, Paris, MNR 411.12

1b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Raising of the Cross, panel, 460 x 340 cm (centre panel) and 460 x 150 (each; inner wings). Church of Our Lady, Antwerp [1].13

1c) Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Amandus and Walburga; SS. Eloy and Catherine, panel, 460 x 150 cm (each; outer wings). Church of Our Lady, Antwerp [2].14

1d) Peter Paul Rubens, The Ship Miracle of St Walburga, 1610–11, panel, 75.5 x 98.5 cm (predella). Museum der bildenden Künste, Maximilian Speck von Sternburg Foundation, Leipzig, 1589.15

1e) Peter Paul Rubens, Angels carrying the Dead Body of St Catherine of Alexandria, panel, c. 75.5 x 98.5 cm. Present whereabouts unknown, presumably lost since 1827.16

1f.I) Peter Paul Rubens, The Elevation of the Cross, c. 1637–8, oil on paper, backed by canvas, 60 x 126.5 cm (later enlarged to 70 x 131.5 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 906.17

1f.II) Jan Witdoeck after Peter Paul Rubens (1f.I), The Raising of the Cross, 1638, etching with engraving (printed from three plates), 1,255 (sheet size (trimmed to image)) x 1,055 mm. BM, London, R,3.74.18

2) (paired since 1824 with 1b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Descent from the Cross (triptych), 1612–14, panel, 421 x 322 cm (centre panel); The Visitation, 421 x 153 cm (inner side of left-hand panel); The Presentation in the Temple, 421 x 153 cm (inner side of right-hand panel); St Christopher and the Hermit, oil on two panels, each 421 x 153 cm (exterior wings of the closed altarpiece).19

3) (after DPG40A and before 1c) Peter Paul Rubens (?), St Amandus (twice) and St Walburga, c. 1610, pen and brown ink, 244 x 148 mm; signed in a different hand; inscriptions in Latin, Greek and Dutch on the verso. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, Princes Gate Bequest, D.1978.PG.54 [3].20

Chiesa Nuova series and other altarpieces21

4a.I) (study for 4a.IV) Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Gregory, Domitilla, Maurus and Papianus, 1606, canvas, 146.5 x 120 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin (on loan from the Bundesrepublik Deutschland).22

4a.II) (modello for 4a.IV) (school of) Peter Paul Rubens, St Gregory, with SS. Maurus and Papianus; St Domitilla with SS. Nereus and Achilleus, panel, 61.5 x 46.5 cm. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, Princes Gate Bequest, P.1978.PG.352.23

4a.III) ?Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Gregory, Domitilla, Maurus and Papianus, 1606, black chalk and ink, 735 x 435 mm. Musée Fabre, Montpellier, 3704.24

4a.IV) Peter Paul Rubens, The Madonna of Vallicella adored by St Gregory with St Maurus and St Papianus; St Domitilla with St Nereus and St Achilleus, 1606–7, canvas, 477 x 288 cm, made for the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella), Rome; since 1811 Musée de Grenoble, MG 97 [4].25

5a) (modello for 5c.I and 5c.II) Peter Paul Rubens, St Gregory with St Maurus and St Papianus; St Domitilla with St Nereus and St Achilleus, April–May 1608, canvas, 44 x 66 cm. Salzburger Barockmuseum (Rossacher collection), Salzburg, 0316.26

5b.I) formerly attributed to Anthony van Dyck after Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Domitilla, Nereus and Achilleus, pen and brown ink and brown wash over graphite, 148 x 109 mm. BM, London, 1895, 0915.1060.27

5b.II) formerly attributed to Anthony van Dyck after Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Gregory, Maurus and Papianus, pen and brown ink and brown wash over graphite, 151 x 131 mm. BM, London, 1895,0915.1061.28

5c.I) Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Gregory, Maurus and Papianus, 1608, slate, 425 x 280 cm. Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome.29

5c.II) Peter Paul Rubens, SS. Domitilla, Nereus and Achilleus, 1608, slate, 425 x 280 cm. Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome.30

5d.III) (modello for 5d.IV) Peter Paul Rubens, Madonna della Vallicella adored by Angels, April–May 1608, canvas, 86 x 57 cm. Gemäldegalerie der Akademie, Vienna, 629.31

5d.IV) Peter Paul Rubens, Madonna della Vallicella adored by Angels, 1608, slate, 425 x 250 cm. Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome.32

6a) (modello for 6b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, panel, c. 65 x 50 cm. Present whereabouts unknown; presumably lost.33

6b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, c. 1609, panel, 309 x 241.5 cm. St Paul, Antwerp [5].34

6c) (after nos 6a, 6b and ?DPG40A and ?DPG40B) (Attributed to) Jan de Bisschop, The Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, c. 1660–70, drawing, c. 730 x 480 mm. Present whereabouts unknown (Ludwig Burchard collection; G. de Leval collection, Brussels; 1978: John P. Hardy collection; photo copyright IRPA-KIK, Brussels) [6].35

6d) (after nos 6a, 6b, and ?DPG40A and ?DPG40B) (Attributed to) Jan de Bisschop, after Rubens, The Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, black chalk, brush in brown, with brown wash, 365 x 497 mm. Albertina, Vienna, 15103 [7].36

7a) (modello for 7b) Peter Paul Rubens, Scenes from the Life of Count Allowin (later St Bavo) or The Conversion of St Bavo, 1611–12, oak panel, 107 x 82 cm (central panel), 107 x 41 cm (each wing). NG, London, NG57.1–3.37

7b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Conversion of St Bavo, 1624, canvas, 475 x 280 cm (arched at the top). St Bavo, Ghent.38

Female saints

8a) (study for 4a.I) Peter Paul Rubens, Bust of St Domitilla, 1606–7, paper mounted on panel, 88.5 x 67.5 cm (originally 88.5 x 61 cm). Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti, Bergamo, 447.39

8) . (attributed to) Peter Paul Rubens, St Catherine in the Clouds, c. 1620–30, signed P. Paul Rubens fecit, etching and engraving, 293 x 198 mm. BM, London, R,4.45.40

8c) Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert after Rubens, Sancta Catharina Virgo et Martyr, inscriptions, engraving, 382 (trimmed) x 240 mm. BM, London, R,4.44.41

8d.I) Roman, The Townley Caryatid, c. 140–160, Pentelic marble, h. 220 cm. BM, London, 1805,0703.44.42

8d.II) After Peter Paul Rubens (original drawing lost), Caryatid, Latin inscriptions, black chalk on white paper, 330 x 227 mm (larger Talman album, fol. 187, no. 76). Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.43

8d.III) (grisaille) Peter Paul Rubens, Two Guardian Angels on the outer wings of the Resurrection Triptych (Triptych for Jan Moretus I and Martina Plantijn), 1611–12, panel, 185 x 47.7 cm (each). Antwerp Cathedral.44

Male saints

9a) Style of Peter Paul Rubens, St Augustine (?), panel, 38 x 17 cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, A 154.45

9b) After Peter Paul Rubens, Head of St Amand, after c. 1610, black, red and white chalk, washed with brown ink, white heightening on violet paper, 326 x 202 mm. Ecclesiastical collection, Austria.46

9c) Peter Paul Rubens, St Thomas (part of a series of twelve Apostles: Apostelada Lerma), 1610–12, panel, 108 x 83 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1654.47

Older masters

10a) Polidoro da Caravaggio or Peter de Kempeneer, retouched by Rubens, St Paul the Apostle, inscriptions, pen and ink with some white heightening and squared for transfer in black chalk, retouched with brown wash and cream and white bodycolour, on blue paper, 208 x 138 mm. Louvre, Paris, 20.244.48

10b) Anonymous 16th century (Dierick Vellert), retouched by Rubens (?), Interment of a Monk at Night, attended by a Bishop, pen and black ink with brush and brown wash and white heightening on dark brown prepared paper, d 285 mm. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth, 353.49

10c) Paolo Veronese, The Consecration of St Nicholas, 1562, canvas, 286.5 x 175.3 cm. NG, London, NG26.50

10d) .Albrecht Dürer, The Apostles John and Peter and The Apostle Paul and the Evangelist Mark, monogrammed AD and dated 1526, panel, 212.8 x 76.2 cm (left panel), 212.4 x 76.3 cm (right panel). Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich, 545 and 540.51

10e.I) Antonello da Messina, fragments of the San Cassiano Altarpiece, c. 1475–6, panel, 115 x 63 cm (centre panel), 55.5 x 35 cm (left panel), 56.8 x 35.6 cm (right panel). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG_2574.52

10e.II ) Copy by David Teniers II after part of Antonello’s San Cassiano Altarpiece (10e.I), St George and St Cecilia, c. 1650–56, panel, 23.5 x 17.3 cm. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, Princes Gate Bequest, P.1978.PG.439.53

10f) Paolo Veronese, SS. Geminianus and Severus, c. 1560 (painted for San Geminiano, Venice), canvas, 341 x 240 cm. Galleria Estense, Modena, 4187.54

10g) Titian, Madonna with Child and Saints (Madonna dei Frari), 1533–5, oil on panel transferred to canvas, 388 x 270 cm. Vatican Museum, Rome, 40351.55

10h) Hendrick Goltzius, St Andrew, 1589, inscriptions, engraving, 15 x 10.5 cm (no. 2 of Twelve Apostles). BM, London, 1853,0709.5.56

Other pictures by Rubens

11a) Peter Paul Rubens, St Joachim (or Moses?) and St Anne (or St John the Baptist?) on the back of Three and Four Music-Making angels, c. 1615–20, panel, 212 x 98 cm each. Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, GE 136 and GE 139.57

11b) Peter Paul Rubens, Sketch for the crowning section of an altar frame, c. 1616–17, panel, 46.3 x 64.1 cm. Rubenshuis, Antwerp, RH.S.194.58

Interior of the Burcht Church/St Walburga’s, Antwerp

12a) Ambrosius Francken I or Frans Francken I, Triptych of the altar of the Guild of the Smiths made for the Church of Our Lady, Antwerp, St Eligius of Noyon preaching in the Church of St Walburga, Antwerp (centre panel), St Eligius visits the Prisoners (inner side of left wing), St Eligius helps the Crippled and Buries the Dead (inner side of right wing), (grisaille) St Eligius in his Smithy (outer side of left wing), (grisaille) Episcopal Ordination of St Eligius (outer side of right wing), dated 1588, panel, 250 x 188 cm (centre panel), 260 x 89 cm (each wing). KMSK, Antwerp, 576–80 [8].59

12b) Antoon Gheringh, View of the Interior of St Walburga, Antwerp, c. 1661–9, canvas, 115 x 141 cm. St Paul, Antwerp [9].60

Copy

13) 19th-century English after DPG40A–B, SS. Amandus and Walburga and SS. Eligius and Catherine of Alexandria, graphite underdrawing, brush and watercolour on ivory wove paper, 169 x 121 mm. Private collection.61

1

Peter Paul Rubens

The raising of the cross, 1610-1611

Antwerp, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Antwerpen)

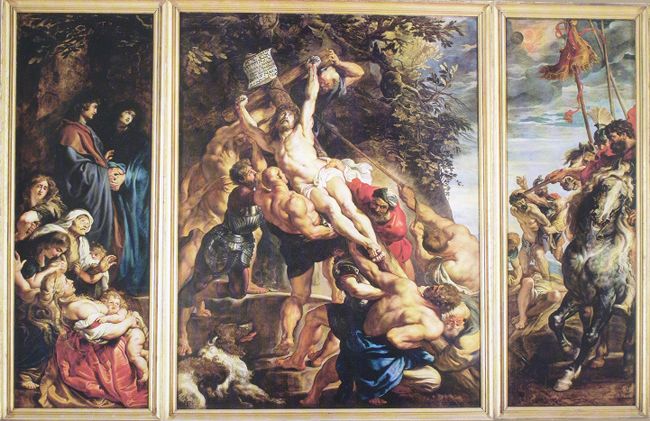

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Amandus and Walburga (left) Saints Eligius (Eloy) and Catherine of Alexandria (right), 1610-1611

Antwerp, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Antwerpen)

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Amandus (twice) and Walburga, c. 1610

London (England), Courtauld Institute of Art, inv./cat.nr. D.1978.PG.54

4

Peter Paul Rubens

The Madonna of Vallicella adored by Saint Gregory with Saint Maurus, and Saint Papianus; Saint Domitilla, with Saint Nereus and Saint Achilleus, 1607-1607

Grenoble, Musée de Grenoble, inv./cat.nr. MG 97

5

Peter Paul Rubens

Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, c. 1609

Antwerp, Sint-Pauluskerk (Antwerpen)

6

attributed to Jan de Bisschop after Peter Paul Rubens

Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament

London (England), Farnham (Surrey), Germany, private collection Ludwig Burchard

7

attributed to Jan de Bisschop after Peter Paul Rubens

Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 15103

8

Ambrosius Francken (I) or attributed to Frans Francken (I)

Saint Eligius preaches in Antwerp, 1588 (dated)

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, inv./cat.nr. 576

9

Antoon Gheringh

Interior of the St Walburga church, Antwerp, 1661-1669

Antwerp, Sint-Pauluskerk (Antwerpen)

DPG40A

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Amandus and Walburga, c. 1610

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG40A

DPG40B

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Eloy (Eligius) and Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1610

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG40B

DPG40A and DPG40B are the modelli for the outer sides of the wings of the altarpiece of The Raising of the Cross commissioned from Rubens in 1610 for the high altar of the Burcht or Borcht Church in Antwerp, also known as the church of St Walburga (or Walpurgis).62 This church was near the harbour, and St Walburga was the patron saint of seamen. The church was demolished in 1817,63 and the altarpiece is now in Antwerp Cathedral (Related works, no. 1b–c) [1-2]. There the Raising of the Cross is presented as the counterpart of Rubens’s Descent from the Cross (1612–14, painted for the Cathedral; Related works, no. 2), since they were returned from Paris in the winter of 1815–16.64 At the time it was the largest altarpiece in the Netherlands.65

Although attributed to Rubens in Britton’s 1813 inventory of Bourgeois’ collection, and by Denning in his manuscript catalogues of 1858 and 1859, Richter and Sparkes in 1880 considered DPG40A–B to be by ‘school of Rubens’, and that was followed by all subsequent DPG cataloguers until 1953, when Ludwig Burchard wrote that part of the catalogue and called them Rubens again.66 Clearly the previous cataloguers had not noticed that Rubens scholars including Rooses in 1888 and 1903 and Burchard in 1926 were convinced that they were by Rubens himself. The attribution is now not doubted. The Dulwich panels are possibly first documented at The Hague in 1747 as part of the collection of the painter and dealer Jacques Ignatius de Roore (1686–1747), who owned other works by Rubens as well.67 The pictures were then joined together – indicated by two aligning peg holes, now visible on the back (see Technical Notes). It was not until c. 1947 that they were separated and given two inventory numbers (at first DPG40 and 40A; now DPG40A and 40B).

In December 1608 Rubens returned to the Netherlands from Italy, and in September 1609 he was appointed court painter to Archduke Albrecht and Archduchess Isabella, marking him out as one of the Spanish Netherlands’ leading painters. That position left him free to take private commissions such as the altarpiece for St Walburga’s. In June 1610 the contract for the altar was signed, and the altarpiece was installed in the same year, but the wings had still to be painted. Rubens probably completed the altarpiece in the winter of 1610, allegedly working in the church behind a curtain.68 His bill of 2,600 guilders was apparently largely paid by the Antwerp merchant and collector Cornelis van der Geest (1577–1638), who had links with the church.69 He received the final payment in 1613.70 The altarpiece consisted of the Raising of the Cross, depicted as a single scene on the central panel, and the two inner wings. The two outer wings depicted four saints, for which DPG40A and 40B are the modelli. In addition there were painted angels and God the Father, and a pelican in gilded wood on top, probably something like the frame for the altar in the Jesuit Church in Antwerp, known from a sketch for a crowning section of an altar frame, with the Madonna and Child in the middle, but also with cut-out angels (Related works, no. 11b). In 1733 a new altar was constructed and parts of the old altarpiece (the predella pictures, the angels and God the Father) were sold to Jacques Ignatius de Roore, the art dealer from The Hague,71 who may also have owned DPG40A and 40B (see Provenance).

The three predella pictures depicted Christ on the Cross flanked by a scene of the life of St Catherine (Related works, no. 1e) and a scene of St Walburga rescuing seamen, of whom she was the patron saint (Related works, no. 1d). The scenes on the predellas suggested the identification of the saints on the outer wings. In the DPG catalogues until 1926 they were said to be Ambrose, Gregory, Catherine and Theresa. However in 1888 Rooses had already said that the left outer wing depicted SS. Eligius and Walburga and the right one SS. Catherine and Amandus. They still have the same names, but the names of Eligius and Amandus have been transposed. In the 1947 catalogue for London and Leeds Burchard identified them correctly. The paintings depict the monumental, statuesque figures of two pairs of saints, Amandus and Walburga and Eligius and Catherine. The first three were associated with the introduction of Christianity into the Antwerp region, while a local tradition associated St Catherine with St Walburga.72 On the left we see Amandus of Maastricht, who died in 679 and who was known as Apostolo Flandriae (the Apostle of Flanders), and Walburga depicted as an abbess. She was an English noblewoman who became abbess of the Benedictine monastery at Heidenheim in Germany and died there c. 776.73 According to a 15th-century Antwerp legend she had lived for several years in the crypt of the church, when she was on her way to Germany. On the right is Eligius or Eloy, Bishop of Tournai (d. 660), patron saint of goldsmiths, shown here with his hammer; he was also styled Apostle of Flanders. The important role played by both male saints in the conversion of the people of Flanders in the early Middle Ages brought them to the fore again during the Counter-Reformation. On the right, Catherine of Alexandria’s status as a martyr is indicated by the sword and palm, but she is not shown with her usual attribute, the wheel (for more usual depictions of the saint see Related works, nos 8b, 8c). Since the 13th century St Catherine had been a patron of the Burcht or St Walburga’s Church, with St Walburga.74 That is why Rubens emphasized the female saints in the Dulwich modelli: he had angels hold crowns above their heads.

Before we discuss the genesis of the altarpiece for St Walburga’s and its stylistic roots, we must analyse two things related to DPG40A–B. Two drawings made by or related to the 17th-century Dutch dilettante-artist Jan de Bisschop (1628–71; Related works, nos 6c–d) [6-7] depict the two Dulwich modelli or very similar compositions.75

It is not clear why and when De Bisschop made those drawings, and whether he visited Antwerp or the modelli were already in The Hague, where they were possibly sold at auction in 1747.76 It is possible that the drawings are related to an unexecuted project by De Bisschop to provide examples for contemporary Dutch or European artists in general, as a sequel to his publications – Signorum veterum icones (1668–9), with 112 prints after Antique statues, and Paradigmata graphices variorum artificum (posthumously published in 1671), with 57 prints after drawings by Italian masters, probably made in the 1660s.77 In the drawings the Dulwich modelli are shown as the inner wings of a triptych, of which the middle part looks very much like the altarpiece of The Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament for the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament in St Paul’s, the Dominican Church in Antwerp (finished c. 1609; Related works, no. 6b) [5]. There are however small differences between the De Bisschop drawings and the Dulwich modelli. In the drawing by De Bisschop that has disappeared (Related works, no. 6c) [6] all four figures seem even more voluminous than in DPG40A–B, and on their way to becoming the figures in the outer wings of the altarpiece. The crozier of St Amandus protrudes above his mitre, whereas in DPG40A the crozier is painted over the right leg of the angel; on the left, above St Amandus, columns are visible and there are curtains, and the lower part of the crozier of St Walburga is visible. In DPG40B there seems to be more space to the left of the hand of St Eligius; above his head and above the angel curtains are depicted by De Bisschop which are absent from DPG40B. The sword of St Catherine is more upright, whereas in DPG40B it leans slightly to the left. In the Vienna drawing by De Bisschop (Related works, no. 6d) [7] these features are even more pronounced: there seem to be more columns and curtains. It is not clear whether De Bisschop made variations on the images that he saw, or whether he had other examples before him than DPG40A and B.

Burchard had suggested that the De Bisschop drawings (including those of the Dulwich modelli) showed Rubens’s initial version of the altarpiece for St Paul’s, a theory he later rejected. In 1999 Cynthia Lawrence proposed that De Bisschop’s drawings were of Rubens’s original design for a winged altarpiece for the high altar of St Walburga’s. She argued that his original design was rejected; the central panel alone was produced as an altarpiece for St Paul’s, and the designs with the saints became the outer wings of Rubens’s next attempt at an altarpiece for the church of St Walburga, the Raising of the Cross. Since Burchard, authors had assumed that De Bisschop had combined the modelli for two different altarpieces in one drawing: the modelli at Dulwich (or similar pictures) with the modello for The Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, the painting in St Paul’s, inspired by Raphael’s Disputà in the Stanza delle Segnatura in the Vatican. Burchard thought the Dulwich pictures had been joined to that by a later owner or dealer. Vlieghe suggested that they had been joined by the patron of both altarpieces, Cornelis van der Geest. Another possibility is that De Bisschop had fictively combined them, and adjusted the motifs to the format of his drawings.78

Lawrence’s argument is both iconographically and compositionally rather convincing, but was published too late to be discussed in the Corpus Rubenianum volume of Judson (2000), as was Heinen’s book of 1996. Both Heinen in 1996 and Lawrence in 1999 and 2005 emphasize the importance of Counter-Reformation ideas for the way Rubens designed the altarpiece. The local conditions made it possible for Rubens to compose an imposing altarpiece. The altar was extremely high: it was built over a street, and you had to climb nineteen steps before you reached it (for an earlier view of the church see the central panel of the altarpiece by Ambrosius Francken I (1544/5–1618), St Eligius of Noyon preaching in St Walburga Church, Antwerp (1588; Related works, no. 12a) [8].79 Rubens then placed the scene with the Raising of the Cross above both the central panel and the two inner wings: it must have seemed like you were present at the scene on Golgotha. Lawrence says that the St Walburga’s was a Gesamtkunstwerk with pictures and statues in the nave before Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) made his Roman churches with statues of the Apostles mounted on the columns of the nave between the 1620s and the 1660s.80 In 1661 Antoon Gheringh (1630/37–68) painted a view of St Walburga’s with the altarpiece by Rubens far in the middle distance (Related works, no. 12b) [9], a faint shadow of the overwhelming impression the church must have made on the 17th-century visitor.

Burchard’s observation that Rubens reused the cherubs from the Dulwich modelli and the Raising of the Cross altarpiece in the Holy Sacrament picture certainly indicates that the works are closely related.81 The cherub crowning St Catherine with flowers in the right wing of the triptych in De Bisschop’s drawings and in the Dulwich modello also appears in the upper left-hand side of the Holy Sacrament (but now holding a book). Similarly, the cherub on the upper left of the central panel of De Bisschop’s drawings was reversed and placed on the right exterior wing of the Raising of the Cross, where it now holds a crown of flowers above St Catherine.

The over life-size statuesque figures of two pairs of saints on the outer wings of the altarpiece were visible on the Alltagsseite, the ‘everyday side’, not on festive days, as then the altarpiece would have been opened. They show, however, notable differences from the Dulwich modelli, chief amongst these being that in the Antwerp altarpiece there is a single cherub above each pair of saints; they hold the saints’ mitres, whereas in the Dulwich modelli they are crowning the female saints; and the figure of St Eligius and the face of St Amandus are completely different. The clothes they wear are different too: in the modelli Rubens only indicated the colours, whereas in the outer wings they are heavily decorated silks and damasks, in different colours, except for St Catherine who still wears white. It has been suggested that the stole that St Amandus is wearing over his mantle could be English embroidery, saved from religious troubles and exported to Flanders in the 16th century.82 The male saints are no longer wearing their mitres as in the Dulwich modelli: the cherubs are holding them above their heads. According to J. R. Martin (1969) this was to stop them towering over the females – an aesthetic reason. It is however more probable that the consecration of St Amandus and St Eligius as bishops is depicted.83 See for instance the picture by Veronese in the National Gallery where St Nicholas is consecrated and an angel is holding his mitre, crozier and stole above him (1562; Related works, no. 10c) and one of the grisailles on the outer wings of the altarpiece dedicated to St Eligius by Ambrosius Francken, depicting the Consecration of St Eligius by two other bishops (Related works, no. 12a) [8]. However why Rubens changed the emphasis on the outer wings of the altarpiece from the female saints – the patron saints of the church – in the modelli to the male saints still needs some explanation. It might be suggested that this emphasis on the militant St Amandus and St Eligius, who had brought Christianity to Flanders, was better suited to the Counter Reformation views of Rubens’s patrons than honouring the female patron saints of St Walburga’s.

Rubens evidently first considered placing the figures in niches, in imitation of marble sculptures, as he had done in pictures now in Vienna (Related works, no. 11a): these are roughly sketched in the modelli, but not present in the final altarpiece. The figures are depicted both realistically and as statues.84 Martin also noted in 1969 that it was significant that the sketches are about the same size as an oil sketch by Rubens of the altarpiece’s central scene and inner wings in the Louvre (Related works, no. 1a), making it likely that they were made at the same time, presumably to display the design to his patrons. In the modello in the Louvre the two thieves are depicted twice, on the central panel and again on the right wing, a sign that Rubens had changed his mind. According to Martin the Dulwich modelli must have been designed as the inner wings of the altarpiece. Held does not agree in his entry on the Louvre sketch.85 Lawrence in 1999 however, does: according to her at this stage Rubens was planning a scene of Moses and the Brazen Serpent on the outer wings of the St Walburga altarpiece, and the Dulwich modelli on the inner wings.86

The saints in both the modelli and the outer wings are related to the figures in Rubens’s St Gregory surrounded by other Saints painted for the church of the Oratorians, the Chiesa Nuova or Santa Maria in Vallicella, in Rome, in 1606–7, and now in Grenoble (Related works, no. 4a.IV) [4]. During a trial hanging the clergy were not satisfied, and Rubens himself found his picture literally too shiny: the older miraculous Vallicella Madonna that had to be included in Rubens’s picture would hardly be visible. So Rubens kept the picture, painted his own Madonna and Child, and placed it by his mother’s grave in St Michael’s, Antwerp. The main characters of this picture – the voluminous figure of St Gregory and the princess-like female martyr, St Domitilla – were motifs that Rubens later developed, and eventually used for St Amandus and St Catherine in DPG40A–B.

Between February and October 1608 Rubens painted a new central composition on slate panels, and also two side panels with three standing saints each (Related works, nos 5c.I–IV).87 Those saints look like the ones in the foreground of DPG40A–B (St Amandus and St Catherine), especially in their voluminous forms. However St Gregory is reaching out with his right hand into the space of the viewer and holding a book in his left hand, whereas in DPG40A (and on the outer wings of the altarpiece) St Amandus holds the book with both hands. In the Grenoble painting St Domitilla is depicted in profile, looking over her shoulder at the viewer. Rubens changed that in the second Vallicella picture (Related works, no. 5c.II): there she is shown almost completely frontally, in contrapposto, similar to one of the guardian angels in the outer wings of the Resurrection triptych in Antwerp Cathedral (1611–12; Related works, no. 8d.III), which is in turn based on a Roman caryatid now in the British Museum (Related works, no. 8d.I–II). A drawing in the Courtauld Institute made by Rubens after DPG40A (Related works, no. 3) [3] shows St Amandus bare-headed, as he would be in the St Walburga altarpiece. Urbach suggested that the bareheaded St Thomas in the Prado, who looks very much like the St Amandus in Antwerp, was inspired by a print by Hendrick Goltzius of St Andrew, dated 1589 (Related works, no. 10h), which in turn goes back to figures painted by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528; such as Related works, no. 10d).88

In general one can say that the composition of DPG40A–B and the outer wings of the Raising of the Cross is derived from Italian sacra conversaziones where we see a Madonnna and Child in the middle, often on a throne, flanked by standing saints. An example is the San Cassiano Altarpiece by Antonello da Messina, now in Vienna, that was in Venice until 1620 (Related works, no. 10e.I–II). Rubens however depicts only the standing saints. Several sources have been proposed for Rubens’s bishops in their voluminous clothes, such as 16th-century drawings retouched by Rubens – bishops by Polidoro da Caravaggio (?) (1499–1543) and by Dirck Vellert (1480/85–c. 1547), if that indeed was worked on by Rubens (Related works, nos 10a, b). For the stately figures Rubens also could have looked at the Four Apostles by Albrecht Dürer (1526), now in Munich (Related works, no. 10d). However they are not wearing decorated robes. For those Rubens could have looked at 16th-century Northern Italian pictures such as Titian’s Madonna dei Frari, now in the Vatican Museums, and especially the spectacular picture by Paolo Veronese, SS. Geminianus and Severus, at the time in San Geminiano in Venice (Related works, nos 10f, g);89 the latter picture is however much lighter that the outer wings of the Raising of the Cross, with their dark background. Martin suggested that the figures of St Catherine and St Amandus were the basis for Rubens’s later images of St Catherine and St Ambrose painted for the Jesuit Church in Antwerp, which was dedicated in 1621 (the paintings were destroyed by fire in 1718; see under DPG125).90 Earlier, in 1611–12, in the sketch for the later altarpiece for St Bavo in Ghent (now in the National Gallery, London) the St Catherine of DPG40B is St Gertrude in white on the left hand side of the picture (Related works, no. 7a).91

1

Peter Paul Rubens

The raising of the cross, 1610-1611

Antwerp, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Antwerpen)

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Amandus and Walburga (left) Saints Eligius (Eloy) and Catherine of Alexandria (right), 1610-1611

Antwerp, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Antwerpen)

5

Peter Paul Rubens

Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament, c. 1609

Antwerp, Sint-Pauluskerk (Antwerpen)

6

attributed to Jan de Bisschop after Peter Paul Rubens

Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament

London (England), Farnham (Surrey), Germany, private collection Ludwig Burchard

7

attributed to Jan de Bisschop after Peter Paul Rubens

Real Presence in the Holy Sacrament

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 15103

8

Ambrosius Francken (I) or attributed to Frans Francken (I)

Saint Eligius preaches in Antwerp, 1588 (dated)

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, inv./cat.nr. 576

9

Antoon Gheringh

Interior of the St Walburga church, Antwerp, 1661-1669

Antwerp, Sint-Pauluskerk (Antwerpen)

4

Peter Paul Rubens

The Madonna of Vallicella adored by Saint Gregory with Saint Maurus, and Saint Papianus; Saint Domitilla, with Saint Nereus and Saint Achilleus, 1607-1607

Grenoble, Musée de Grenoble, inv./cat.nr. MG 97

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Saints Amandus (twice) and Walburga, c. 1610

London (England), Courtauld Institute of Art, inv./cat.nr. D.1978.PG.54

Notes

1 ‘The two panels were till recently joined together’, London/Leeds 1947–53, no. 45. However the report by Ian Tyers shows that the pieces of wood originated in different parts of Europe: Tyers 2014, pp. 10–15.

2 Held (1980, i, p. 481) incorrectly stated that in the 18th century the picture was in the collection of Pietro Gentile in Genoa and later of the dealer W. Buchanan: this is a confusion with DPG148, Rubens’s St Ignatius exorcising: see Provenance of that. ‘Consul Smith’, mentioned between Desenfans and Bourgeois, is an invention by Judson (2000, pp. 111 and 115 (twice under Provenance)).

3 Twee Bisschoppen en twee Sanctinnen, en 2 Kindertjes, door dito [Rubens], h. 25 en een halve d., b. 19 en een halve d. (Two Bishops and two Female Saints, and two Children, by ditto [Rubens], c. 65 x 50 cm), ƒ102 (ex. MH, The Hague). The dimensions seem about right for DPG40A–B, assuming that ‘d’ means duim (inch).

4 In 1980 Peter Murray suggested that the picture was in Desenfans’ hands in 1786: Desenfans private sale, 125 Pall Mall, 8ff. April 1786 (Lugt 4022), lot 384: ‘an Emblematical of the Church, 33 x 29, £70’ (2 ft 9 x 2 ft 5 on panel), but this seems unlikely as the picture with this title appears in his 1804 Insurance list, attributed to Van Dyck (no. 112: ‘Vandyck – an Emblematical’; now School of Van Dyck, DPG81, Charity), along with DPG40A and 40B, then still one picture (no. 101: ‘Rubens – Saints’).

5 See De Roore sale catalogue (Lugt 672) under Provenance (note 34).

6 ‘DITTO [= Sir P. P. Rubens]. Historical Sketch of two bishops and two female saints; the females have palms of martyrdom; it is a most admirable sketch, full of vigour and richness of colour.’

7 ‘A small Sketch, representing four Saints. St. Ambrose, St. Gregory, St. Catherine, and St. Theresa; two angels descend from above to crown the female saints. A very spirited study for a large picture. St. Catherine is here represented with the sword by which she was beheaded, and not with the wheel, as is usual. There is something in the elegant turn of the figure which reminds us of Parmigiano. I am not aware of the existence of any large picture painted from this study, nor of any engraving from it.’

8 A gauche, vieux saint la tête baissée, et sainte. A droite, saint évéque [sic] regardant une autre sainte, sa voisine, qui tient sa palme et s’appuie sur une longue épée. Dans les airs, anges leur apportant des couronnes (quart de nature). (On the left an old saint, looking down, and a female saint. On the right a holy bishop looking at another female saint, next to him, who holds her palm and leans on a long sword. In the air angels bringing them crowns (one quarter life-size)).

9 p. 106, note 9: Liess does not believe that the Vienna drawing was made after a composition by Rubens.

10 In note 258 Heinen refers to Rooses (1886–92, ii (1888), pp. 72–3 and pl. 99), where however the wrong names are given for the saints.

11 Tyers 2014, pp. 10–15.

12 RKD, no. 23338: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23338 (June 29, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 178, fig. 3, under DPG40A, 40B; Judson 2000, pp. 95–8, no. 20a, fig. 62; Jaffé 1989, p. 173, no. 131; Held 1980, i, pp. 479–81, no. 349, ii, pls 343–4.

13 RKD, no. 23184: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23184, RKD, no. 23185: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23185 and RKD, no. 23386: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23186 (all three June 29, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 177, fig. 1, under DPG40A, 40B; Judson 2000, pp. 88–95, figs 61, 64; Jaffé 1989, p. 174, no. 135ABC; White 1987, pp. 85–95; Held 1980, i, pp. 479–81, no. 349, ii, pl. 343–4.

14 RKD, no. 23321: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23321 (July 1, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 177, fig. 2, under DPG40A, 40B; Judson 2000, pp. 109–11, no. 21, fig. 81 and pp. 113–14, no. 22, fig. 82; Jaffé 1989, p. 174, nos 135D and E.

15 RKD, no. 197996: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197996 (July 1, 2019); Büttner & Heinen 2004, pp. 209–11, no. 39 (U. Heinen); Judson 2000, pp. 116–18, no. 23, fig. 88; R. Hartlieb in Guratz 1998, pp. 118–21, no. I/56; Heinen 1996, pp. 67–8, fig. 4; Jaffé 1989, p. 174, no. 135F; Heiland 1969.

16 Judson 2000, pp. 119–20, no. 25; Jaffé 1989, p. 174, no. 135H.

17 Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 204–7, no. 64 (A. Vergara); Sutton & Wieseman 2004, pp. 248–51, no. 39 (M. E. Wieseman); Judson 2000, pp. 105–9, no. 20k, fig. 77.

18 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_R-3-74 (Aug. 2, 2020); Sutton & Wieseman 2004, p. 251, under no. 39 (fig. 3; M. E. Wieseman). NB: both the dimensions and the inv. no. given here are wrong.

19 RKD, no. 23355: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23355 (Aug. 4, 2020); Judson 2000, pp. 162–90, nos 43–6, figs 135–64; Jaffé 1989, p. 183, nos 189A–E.

20 RKD no. 275587: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/275587 (July 1, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 180, fig. 5, under DPG40A, 40B. According to Heinen however this drawing was made before the modelli: Heinen 1996, p. 287 (note 87). See also White 2003a, p. 806 (doubted by a number of scholars); Heinen 1996, pp. 87, 286 (note 80; Rubens); Logan 1991, p. 314 (Held rightly casts doubt on the authenticity); Braham 1988, pp. 24–5, no. 29 (Rubens); Jaffé 1979, p. 40, fig. 15; Seilern 1971, p. 36; Jaffé 1966b, p. 134 (fig. 2); Seilern 1955, p. 86, no. 54, pl. CVI; Norris 1933, p. 230 (pl. IA).

21 For an overview of the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella) project see Held 1980, i, pp. 537–40. See RKD, no. 295295: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295295 (Oct. 8, 2019).

22 No inventory number is given; RKD, no. 197988: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197988 (June 29, 2019); Lindemann & Contini 2010, pp. 52–3, no. 7; Jaffé 1989, p. 159, no. 62; Held 1980, i, pp. 540–42, no. 396, ii, pl. 386; Bott 1977, pp. 161–4, no. 16; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 53–4, no. 109d, fig. 25 (another sketch is mentioned in the Museum des Siegerlandes, Siegen: ibid., pp. 55–6, no. 109e, fig. 26); Rotterdam 1953–4, pp. 33–4, no. 3, pl. 3 (E. Haverkamp-Begemann).

23 RKD, no. 253725: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253725 (Sept. 4, 2019). See also http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/2753e2b0.html (Sept. 4, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 159, no. 63 (Rubens); Held 1980, i, pp. 640–41, no. A33 (under Questionable and rejected attributions), ii, pl. 497; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 57–8, no. 109g, fig. 30 (parts heavily repainted by a different and less skilled hand).

24 RKD, no. 255289: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/255289 (Sept. 4, 2019); Jaffé 1977, fig. 322 (Rubens); Bott 1977, p. 204, no. 32 (Rubens); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 56–7, under no. 109f (copy after 4a.IV).

25 RKD, no. 191946: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/191946 (June 29, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 159, no. 64; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 43–58, no. 109, fig. 23.

26 H. Widauer in Schröder & Widauer 2004, pp. 184–6, no. 20; Jaffé 1989, p. 162, no. 77; Held 1980, i, pp. 543–5, no. 398, ii, pl. 388.

27 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1895-0915-1060 (Aug. 2, 2020); Rowlands 1977, pp. 38–9, no. 30a. This and the next drawing after Rubens, previously attributed to Van Dyck, were considered by others to be preparations by Rubens himself for the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella) pictures: see Rowlands 1977, pp. 38–9, nos 30a–b; Held 1972, pp. 96, 98–9 (fig. 46; Rubens).

28 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1895-0915-1061 (Aug. 2, 2020); Rowlands 1977, pp. 38–9, no. 30b. See also the preceding note.

29 RKD, no. 105547: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/1055487 (Sept. 10, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 163, no. 82b.

30 RKD, no. 105548: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/105548 (Sept. 10. 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 163, no. 82c.

31 RKD, no. 263313: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/263313 (Sept. 10, 2019); A. van Suchtelen in Woollett & Van Suchtelen 2006, pp. 208–13, no. 29; Trnek 2000, pp. 18–22, no. 1, fig. 1; Held 1980, i, pp. 542–3, no. 397, ii, pl. 387, col. pl. 1.

32 RKD, no. 105545: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/105545 (July 16, 2019); Aikema 2006, pp. 225–8; Jaffé 1989, p. 163, no. 82a.

33 RKD, no. 252261: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/252261 (Sept. 10, 2019); Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), pp. 78–9, no. 56a.

34 RKD, no. 191947: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/191947 (July 1, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 165, no. 88 (c. 1609); Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), pp. 73–8, no. 56, fig. 99.

35 RKD, no. 252262: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/252262 (July 2019); Judson 2000, p. 111, Copies, no. 1, under no. 21a and p. 115, Copies, no. 1, under no. 22a. See also Held 1980, i, p. 482, under no. 350; Van Gelder 1978, p. 456 (note 16), and Mitsch 1977, p. 204, under no. 102. See also notes 75–77 below (Plomp).

36 RKD, no. 252263: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/252263 (July 1, 2019); https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/?query=Inventarnummer=[15103]&showtype=record (Aug. 4, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 178, fig. 4, under DPG40A, 40B; Judson 2000, p. 111, Copies, no. 2, under no. 21a and p. 115, Copies, no. 2, under no. 22a. See also Held 1980, i, p. 482, under no. 350; Van Gelder 1978, p. 456 (note 16); Mitsch 1977, p. 204, no. 102; Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), p. 78. under no. 56a, copy no. 2, fig. 103. See also notes 75–77 below (Plomp).

37 RKD, no. 194497: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/194497 (June 29, 2019); see also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-kings-clothar-and-dagobert-dispute-with-a-herald#painting-group-info (Sept. 11, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 180, no. 174, Held, i, 1980, pp. 547–50, no. 400, ii, pl. 390; Martin 1970, pp. 126–33, no. 57.

38 RKD, no. 252510: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/252510 (Sept. 11, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 282, no. 768; Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), pp. 107–9, no. 72, fig. 123.

39 RKD, no. 253716: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253716 (Sept. 11, 2019); N. Dacos in Borea & Gasparri 2000, ii, p. 300, no. 17; Jaffé 1989, pp. 158–9, no. 61 (study of a courtesan); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 52–3, no. 109c, fig. 28.

40 See note 21 in the previous paragraph under Peter Paul Rubens. For another impression in the BM see S.5379. For a copy in the Rijksprentenkabinet see RKD, no. 72040: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/72040 (Sept. 11, 2019) and http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.38483 (Sept. 11, 2019).

41 RKD, no. 295456: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295456 (Oct. 8, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_R-4-44 (Aug. 2, 2020); Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), pp. 100–101, under no. 69 (copy). The copy in reverse published by Pierre Mariette is not mentioned by Vlieghe (see RKD, no. 252444: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/252444 (Oct. 1, 2019)); Lepape 2009c.

42 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1805-0703-44 (Aug. 2, 2020); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), p. 76, iii (1995), figs 110–12.

43 RKD, no. 272852: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/272852 (Sept. 11, 2019); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), pp. 74–8, under no. 60 (Copy), iii, fig. 113.

44 RKD, no. 23512 (left wing): https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23512, and RKD, no. 23513 (right wing): https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/23513 (both Sept. 11, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 179, no. 167D–E; Freedberg 1984, pp. 37–8, no. 4, fig. 1; see also Van der Meulen 1994–5, i (1994), text ills 21–2.

45 RKD, no. 252429: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/252429 (July 16, 2019); Casley, Harrison & Whiteley 2004, p. 197; White 1999a, pp. 127–8, no. A 154; Jaffé 1989, p. 171, no. 124; Cleaver, White & Wood 1988, pp. 84–5, no. 22; Held 1980, i, p. 642, A34 (under Questionable and rejected attributions), ii, pl. 499.

46 RKD, no. 275579: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/275579 (Oct. 1, 2019); Müller Hofstede 1967b; see also Eidelberg 1997, pp. 259–60 (note 11) and Heinen 1996, pp. 87, 288 (note 88): the drawing was attributed to Dürer (!) in the 19th century. A very similar drawing is in the Albertina, Vienna: see Eidelberg 1997, pp. 236 (fig. 2), 259 (note 3), Head of a Bearded Man looking down to the right, black chalk, 112 x 95 mm. Eidelberg connects this drawing with a Rubens modello for St Thomas (Related works, no. 9c), but not to St Amandus on the Antwerp altarpiece (Related works, no. 1c).

47 RKD, no. 237571: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/237571 (July 1, 2019); https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/santo-tomas/ (March 16, 2014); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 900–901; Jaffé 1989, pp. 178–9, no. 161; Vlieghe 1972–3, i (1972), p. 44, no. 13, fig. 42.

48 Wood 2010a, i, pp. 416–19, no. 97, ii, fig. 252 (not used for St Amandus, p. 418); Sérullaz 1978, p. 92, no. 93 (used for St Amandus); Jaffé 1977, p. 48L (used for St Amandus; Rubens); Jaffé 1966b, p. 134 (fig. 4; Rubens).

49 RKD, no. 103773: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/103773 (Sept. 17, 2019); Belkin 2009, i, pp. 272–3, no. 146, ii, fig. 377 (as d 280 mm); Jaffé 2002, ii, pp. 248–9, no. 1281 (Vellert; The Exhumation of St Hubert); Jaffé 1993, pp. 172–3, no. 189. NB: according to Christopher White this drawing is not retouched by Rubens: see White 2003b, p. 403, no. 1281.

50 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paolo-veronese-the-consecration-of-saint-nicholas# (Jan. 25, 2021); Penny 2008, pp. xiii, xix, 344–53; Pignatti 1976, i, p. 124, no. 123, ii, figs 365, 367.

51 RKD, no. 289866: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/289866; see also https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artist/albrecht-duerer/vier-apostel-hll-johannes-ev-und-petrus and RKD, no. 289863: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/289863; see also https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artist/albrecht-duerer/vier-apostel-hll-markus-und-paulus (all Sept. 12, 2019); Schawe 2006, pp. 144–7; Anzelewsky 1971, pp. 274–9, nos 183–4, figs 185–8a/b, col. pl. 8 and text figs 118, 119.

52 www.khm.at/de/object/36fa3ecc0b/ (July 16, 2019); Ferino-Pagden, Prohaska & Schütz 1991, p. 24, pl. 15.

53 http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/6e920896.html (July 16, 2019); Vegelin van Claerbergen 2006, pp. 84–5, no. 7.

54 Salomon 2014, pp. 96–7 (fig. 65), 253, no. 14.

55 http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/la-pinacoteca/sala-x---secolo-xvi/tiziano-vecellio--la-madonna-col-bambino-e-santi.html#&gid=1&pid=1 (Jan. 25, 2021); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 44.

56 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1853-0709-5 (Aug. 2, 2020).

57 Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 204–9, nos 44–5; Jaffé 1989, p. 185, nos 197C–D.

58 RKD, no. 22134: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22134 (June 29, 2019); Herremans 2019, pp. 88, 89 (text ill. 22), 173–7, no. 13b, fig. 80; Fabri & Lombaerde 2018, pp. 186–92, no. 9a, fig. 101. According to these authors the sketch is a design for the crowning section of the high altar of the Jesuit Church in Antwerp [NB: curiously, the entries in the Corpus volumes by Herremans 2019 and Fabri & Lombaerde 2018 discuss the same sketch, but there are many differences in dimensions, provenance and interpretation; in 2019 technical notes were added]; Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, p. 220, no. 78; Jaffé 1989, pp. 306–7, no. 924; Held 1980, i, pp. 533–4, no. 395 (then in the collection of Lady Beckett, Yorkshire), ii, pl. 384.

59 http://www.lukasweb.be/nl/foto/sint-eligius-predikt-te-antwerpen (Sept. 8, 2014); RKD, no. 50508: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/50508 (June 29, 2019); see for the wings RKD, nos 50509–505012 (June 30, 2019). According to Vandamme 1988 (pp. 148–9, nos 576–80) this altar was made by Ambrosius Francken I, but according to P. Huvenne (in Baudouin & Huvenne 1985, p. 138) it is attributed to Frans Francken I.

60 RKD, no. 295342: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295342 (Oct. 8, 2019); Judson 2000, pp. 90, 119, 121, 122, fig. 63; Heinen 1996, pp. 45–7, 52, 233 (note 10), fig. 7 (1661); Baudouin 1992a, pp. 59–60, figs 35–6; Baudouin 1992b, pp. 17–19 (fig. 4 (colour), here dated 1664); Baudouin 1988, pp. 190–94 (1669), fig. 6 (1664).

61 Emails Nov. 2013 (DPG40A–B file).

62 For this altarpiece in general see Lawrence 2005; Judson 2000, pp. 88–122, nos 20–28; Heinen 1996; Downes 1980, pp. 108–10; Martin 1969. In 893, when Walburga was canonized, the Burcht Church was renamed after her: Lawrence 2005, p. 256. For the iconography of St Walburga in Flanders, see Stroo 1985.

63 Heinen 1996, p. 232 (note 4).

64 The French troops had brought them to Paris in 1794 for display in the Muséum Central des Arts (later Musée Napoléon) in the Louvre, where art works taken from European cities were shown as war trophies: Maës 2015 (about the Descent from the Cross). In 1824 the Raising of the Cross was installed in Antwerp Cathedral: Judson 2000, p. 91; see also Heinen 1996, p. 232 (note 4).

65 Except for the St Lawrence Altarpiece by Maerten van Heemskerck (570 x 790 cm), made for St Lawrence in Alkmaar (1539–43), since 1582 in Linköping Cathedral, which however consists of two scenes one above the other: Heinen 1996, pp. 71, 269 (note 291), who also refers to Baudouin 1992a, p. 63; see also Thuiskomst 2018. RKD, no. 239114: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/239114 (June 30, 2019).

66 Preceded by his contribution to the catalogue of the London/Leeds exhibition 1947–53.

67 As appears from his sale catalogue of 1747 (see Provenance); and see notes 3 and 5 above.

68 The reason Rubens did that was that he could use the lightfall in the church; see for instance Heinen 1996, pp. 49, 241 (note 61).

69 On Van der Geest as a patron and collector see Van Beneden 2009, pp. 64–7; Held 1957. Van Dyck painted Van der Geest’s portrait: NG, London, NG52 (RKD, no. 48286: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/48286 (Aug. 4, 2020) and https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/anthony-van-dyck-portrait-of-cornelis-van-der-geest, (Aug 4, 2020)); see also Vergara & Lammertse 2012, pp. 320–22, no. 87; T. Posada Kubissa. Willem van Haecht painted a view of his collection being inspected by Archduke Albrecht and Archduchess Isabella (Rubenshuis, Antwerp, RH.S.171): see Van Suchtelen & Van Beneden 2009, pp. 37 (fig. 17), 38, 51–6, 61 (fig. 31), 67 (fig. 35), 68–74 (figs 36–47), 123, no. 10; also RKD, no. 251675: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/251675 (June 30, 2019).

70 The documents were published by Rooses 1886–92, ii (1888), pp. 79–80; for an English translation see Martin 1969, pp. 55–6; see also Heinen 1996, p. 232 (note 2).

71 Judson 2000, pp. 90–91; see also the sale catalogue (Lugt 672), in which several works by Rubens are mentioned, among them the predellas from St Walburga church (nos 28–30) and seven sketches for the Jesuit Church (nos 39–45). See also Van der Stighelen 2006b, pp. 388–9, 409–13, 419.

72 Lawrence 1999, pp. 274, 277.

73 For St Walburga see Münster & Bauch 1979.

74 Lawrence 2005, p. 257; Judson 2000, p. 114. Although all four saints were associated with Antwerp and especially with the Burcht Church, both Murray in 1980 and Held in the same year say that St Walburga had no link with the city. Rubens started on the Dulwich modelli with the idea of honouring the two female patron saints of the church; that changed in the altarpiece, where the focus is on the male saints. See also note 83 below.

75 Frequently there are two versions of the same drawing of the 1660s by Jan de Bisschop; it is known that Constantijn Huygens II (1628–97), another dilettante artist, whose main role from 1672 was secretary to Stadholder William III (later King of England), made copies after drawings by Jan de Bisschop: Van Gelder 1971, p. 212 (who alas does not go deeper into the stylistic differences and affinities between the two amateurs), and Jellema & Plomp 1992, pp. 16–17. Could one of the drawings be by Constantijn Huygens II? Michiel Plomp said that might be possible: email from Michiel Plomp to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 8 Nov. 2014 (DPG40A–B file).

76 Jan de Bisschop, who was an amateur artist (by profession he was a lawyer), was born in The Hague in 1628. So the earliest he could have made these drawings was about 1644 (when he seems to have started his artistic studies with Bartolomeus Breenbergh (1598–1657). He died in 1671. His collection, of which no catalogue is known, consisted of prints and drawings. De Bisschop made at least one other drawing after Rubens (now in Frankfurt), after a picture in the Medici series (in reverse); see RKD, no. 206588: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/206588 (June 30, 2019). That drawing raises a number of questions. Did De Bisschop work from a print? The earliest reproductive prints after the Medici cycle date from the early 18th century. There are some differences from the painting, such as the left nude seen more frontally in the drawing, and the young Marie de’ Medici wears contemporary clothing in the painting whereas in the drawing her costume is more timeless; in addition, in the drawing she covers the lower half of the right nude, while the three nudes in the painting are fully visible. Was it De Bisschop's intention to improve Rubens? If so, did he do the same in the two drawings where the Dulwich modelli seem to figure?

77 The possibility of another project dedicated to reproductions of paintings is suggested by M. Plomp in Jellema & Plomp 1992, p. 39. On the Icones and Paradigmata see Van Gelder, Jost & Andrews 1985; on the Icones, see the blog by Valentina Rubechini, https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/engraved-ornament-project/teaching-art-and-spreading-models-jan-de-bisschop-s-prints-after-anti (Aug. 4, 2020). On the Paradigmata and the number of prints that De Bisschop meant to include see Van Gelder 1971, pp. 222–4.

78 Held 1980, i, p. 482.

79 For the number of steps see Heinen 1996, pp. 47, 238 (note 35). Lawrence (1999, p. 275, fig. 10) shows what the altarpiece in St Walburga’s would have looked like if Rubens’s design as depicted in the De Bisschop drawings had been executed.

80 Lawrence 2005, pp. 265–6. However she does not say, let alone prove, that Rubens was involved in the design of the nave in general and the statues in particular. She says that both Bernini and Rubens were inspired by the visual axes in the Early Christian churches restored by Cardinal Cesare Baronio (ibid., p. 270 (note 41)). In the Corpus volume on architectural sculpture the high altar of St Walburga’s is briefly discussed (Herremans 2019, pp. 68, 69, text ill. 16), but the nave is not mentioned, nor is a possible Early Christian inspiration, and nor is Lawrence’s article of 2005.

81 Lawrence (1999, p. 280) cites Burchard’s material in the Rubenianum (p. 294 (note 78)).

82 Kate Heard in conversation with the authors, 2013; see also Madou 1981.

83 As Heinen also says, 1996, pp. 70, 268–9 (note 282). Clearly Rubens started with honouring the female saints to whom the church of St Walburga was dedicated: see note 74 above.

84 Heinen 1996, pp. 71, 269 (note 290).

85 Held 1980, i, p. 480.

86 Lawrence 1999, pp. 274 (fig. 8), 286 (fig. 20), 287 (fig. 22).

87 For the location of the three panels in the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella) see Downes 1980, p. 68 (fig. C).

88 Urbach 1983, pp. 10–11 (figs 16, 17).

89 For Titian’s influence on the Grenoble picture (Related works no. 4a.IV) see Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 44, and Heinen 1996, pp. 72, 270 (note 304).

90 Martin 1968a, pp. 145 (St Catherine), 168 (St Ambrose / St Amandus).

91 Later, in the altarpiece itself she gets a red dress and a different pose, and no longer looks like St Catherine in DPG40B.