Peter Paul Rubens DPG451

DPG451 – Venus lamenting Adonis (with Cupid and the Three Graces)

c. 1613–15; oak panel, 48.6 x 66.4 cm, consisting of two oak panels, including an addition of c. 16 mm at the top edge (see Technical Notes)

PROVENANCE

?Jeremias Wildens inventory (Inde const Camer opde gaelderye (in the art room near the gallery)), Antwerp, 30 Dec. 1653, no. 649 (Een schetse van Rubens, synde eenen dooden Adonus (A sketch by Rubens, being a dead Adonis));1 Private Sale, European Museum, London, 1792 (no dates known; no Lugt no.), lot 306;2 Private Sale, European Museum, London, 1800 (no dates known; no Lugt no.), lot 439 (‘Rubens; Venus bewailing the death of Adonis, the original sketch for the large picture’);3 Private Sale, European Museum, London, 16 Nov. 1801–1 Jan. 1803 (no Lugt no.), lot 439 (‘Venus bewailing the death of Adonis, the original sketch for the large picture’); not in Desenfans 1802;4 Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 15, no. 134 (‘Middle Room 2nd Floor / no. 12, Death of Adonis. Sketch in one colour for large picture in the possession of Thos. Hope Esq. – P[anel] Rubens’; 2'4" x 3').

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 12, no. 214 (‘CENTRE ROOM – East side; Venus weeping over Adonis; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 392, no. 214; Cat. 1820, p. 12, no. 214 (Venus weeping over Adonis; Rubens); Cat. 1830, p. 11, no. 227 (Vandyke); Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 209, under no. 751;5 Jameson 1842, ii, p. 480, no. 227;6 Clarke 1842, no. 227;7 Denning 1858, no. 227 (Venus weeping over Adonis. A Sketch; Vandyke); not in Denning 1859; Lavice 1867, p. 174 (Antoine van Dyck);8 Sparkes 1876, p. 189, no. 227 (Anthony van Dyck); Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 144, no. 227 (painted in the style of Rubens by his scholars or imitators; formerly attributed to van Dijck); Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), p. 179,9 under no. 696 (Related works, no. 1a) [1]; Richter & Sparkes 1892, p. 128 (not hung); Richter & Sparkes 1905, p. 128, no. 451 (School of Rubens); Cook 1914, p. 254; Cook 1926, p. 236; Evers 1943, pp. 121, 136; Cat. 1953, p. 35 (Rubens); Held 1959, i, pp. 24 (note 2),10 102, under no. 22 (Related works, no. 4b), ii, pl. 23; Jaffé 1967, pp. 4–5, 10 (fig.), 12–13; Morawińska 1974, p. 41, no. 26 [?]; Baudouin 1977, p. 111 (pl. 11), under Related works, no. 1a; D’Hulst 1977, p. 79, under no. 28 (Related works, no.1a); Murray 1980a, p. 115; Murray 1980b, p. 25; Held 1980, i, pp. 361–2, no. 267, ii, pl. 239; Lecaldano 1980, i, p. 120, no. 220 (c. 1614); Bodart 1985, p. 159, no. 144a; Held 1986, p. 92, under no. 57 (fig. 56; Related works, no. 4b); Jaffé 1989, p. 196, no. 253 (c. 1614); Robels 1989, pp. 120 (note 280), 121; Jaffé 1990, p. 702; Lusheck 1995; Jaffé & Plender 1995; Beresford 1998, p. 213; Shawe-Taylor 2000, p. 40; Nichols 2003, pp. 328–9 (note 44); Rosenthal 2005, pp. 145–50, 272–3, fig. 51; Rosen 2008, p. 95, note 15; Tieze 2009, pp. 396 (note 17), 399 (fig. 7), under no. 1121 (Related works, no. 3b); Steinberg 2012, pp. 6, 19, 22–3 (fig.), 25–7; Tyers 2014, pp. 40–42; Sluijter 2015, pp. 305 (fig. V–59), 307; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 181–3, 212; RKD, no. 294326: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294326 (July 3, 2019).

EXHIBITIONS

London 1953–4, p. 65, no. 195; London 1995, pp. 33–5, no. 3 (M. Jaffé and S. Plender); Japan 1999, p. 167, no. 22 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 130–31, no. 37 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Jerusalem 2012, pp. 6, 22–3 (fig.), 25–7, 31.

TECHNICAL NOTES

The panel has a slight convex warp, and consists of two horizontal members with a join that slopes 24 cm to 25.8 cm from the bottom edge. The join has been repaired previously with three rectangular joining blocks in the right half (verso) and, as a result of its having been unevenly reglued at some stage, it is slightly stepped on the front. The addition at the top was added in 1866. The original panel is roughly bevelled on all four sides. Dendrochronology indicates that the panels derived from trees felled between c. 1593 and c. 1620. The bottom board links to a board in a panel described at the time it was analysed as Study of a Head of a Boy by Rubens (Private collection).11 There is raised paint craquelure at the top left. The ground is pale-cream and the under-drawing has been executed in umber. There are several old (restored) scratches and chips, most noticeable in the right shoulder of the uppermost figure and in the centre left edge. The paint is fairly thinly applied, with some crisp impasto in the whites. Previous recorded treatment: 1866, strip at top added, ‘revived’ and revarnished; 1922, varnished; 1936, panel polished; 1953, conserved, Dr Hell; 1995, conserved, S. Plender.

RELATED WORKS

1a) Prime version: Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of Adonis (with Venus, Cupid and the Three Graces), c. 1614, canvas, 212 x 325 cm. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Gift of Saul and Gayfryd Steinberg, New York, to American Friends of the Israel Museum, 2000, B00.0735 [1].12

1b) (Copy after 1a or DPG451?); The Death of Adonis, 200 x 325 cm. Apparently dismembered; present whereabouts unknown.13

2) (Copy after DPG451) Rubens’s Cantoor (Willem Panneels), The Death of Adonis, red chalk, reinforced by pen, on white paper, 172 x 298 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, Rubens’s Cantoor, IV.38 [2].14

Other compositions

3a) Copy after Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Heliades and the River Po, c. 1640–62, canvas, pasted on two boards, 47.1 x 60.2 cm. (fragment of The Fall of Phaeton). Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt, 1121.15

3b) Willem Panneels after Peter Paul Rubens, Venus weeping for Adonis, c. 1631, inscriptions, etching, 78 x 112 mm. BM, London, S.5360.16

4a) Peter Paul Rubens or Anthony van Dyck, Study for a Lament for Adonis, pen in brown, black chalk, 226 x 162 mm. Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, PK.OT.00105.17

4b) Peter Paul Rubens (formerly Anthony van Dyck), Study for a Lament for Adonis, 1603–5, pen and brush and brown ink, 217 x 153 mm. BM, London, 1895,0915.1064.18

4c) Peter Paul Rubens, Study for a Lament for Adonis, c. 1606–7, inscribed Spiritum morientis excipit ore (She revives with the mouth the spirit of the dying [Adonis]), pen and brown ink, 306 x 198 mm. NGA, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1968, 1968.20.1.19

5) Peter Paul Rubens, Lament for Adonis, c. 1602, canvas, 273.5 x 183 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Private collection, France, Photo RKD).20

6a) (modello for 6b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of Adonis, c. 1639, panel, 34.6 x 52.4 cm. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, N.J., 30–458.21

6b) Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders, The Death of Adonis, c. 1639, for the King of Spain, canvas, c. 125 x 300 cm. Present wherebouts unknown, presumably destroyed by the fire in the Alcázar Palace, Madrid, in 1734.22

Details

Dogs

7a) Studio of Rubens or Frans Snijders after Peter Paul Rubens, Three Greyhounds, canvas, 83 x 68 cm. Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick, 95 [3].23

7b) Peter Paul Rubens, Venus attempting to keep Adonis from the Hunt, c. 1610, canvas, 276 x 183 cm. Museum Kunst Palast Düsseldorf, M 2300.24

7c) (studio copy) Peter Paul Rubens, Venus attempting to keep Adonis from the Hunt, panel, 59 x 81 cm. MH, The Hague, 254.25

7d.I) Jan Wildens, Winter Landscape with Hunters and Dogs, signed and dated JAN. WILDENS.FECIT.1624, canvas, 194 x 292 cm. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, 2134.26

7d.II) Jan Wildens, Hunter with Dogs in a Landscape, signed and dated J. Wildens F A 1625, canvas, 198.7 x 299.5 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, GE 6239.27

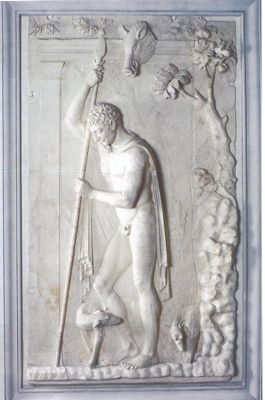

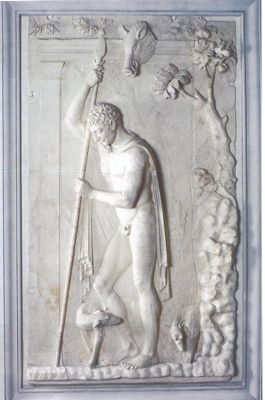

7e) Roman, Adonis at the Hunt, marble relief, h. 177 cm. Galleria Spada, Rome [4].28

Reclining male and female nudes

8a) Peter Paul Rubens, The Martyrdom of St Lawrence, inscribed van dyck, pen in brown, 129 x 195 mm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 1981:15.29

8b) Peter Paul Rubens, Reclining chained Nude, 116 x 271 mm. Staatliche Museen, Berlin, KdZ 26490.30

8c) Peter Paul Rubens, Cephalus lamenting the Death of Procris, pen and brown ink, 255 x 437 mm (recto). Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, N.J., 51–98.31

8d.I) Michiel Coxie, God cursing Cain after the Murder of Abel (Genesis 4:9–15), after 1539, canvas, 151 x 125 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1518.32

8d.II) Adriaen Thomasz. Key (after 8d.I), Cain and Abel, inscribed ADRIAEN THOMAS KEIJE FECIT, panel, 180 x 130 cm. Zanchi collection, Belmont (Switzerland).33

8d.III) Michiel Coxie, touched up by Peter Paul Rubens, after 8d.II, Abel slain by Cain, c. 1608–10, red chalk, red ink, 213 x 207 mm. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, PD.43-1961.34

8d.IV) Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders, Prometheus bound, 1611/12–18, canvas, 242.6 x 209.6 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, W1950–3–1, purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund, 1950.35

9a) (copy after DPG451 (Adonis) and after a figure in 9b), Two reclining Youths, canvas, 47 x 68 cm. Private collection, South America.36

9b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Defeat of Sennacherib, c. 1617, panel, 97.4 x 122.8 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 326.37

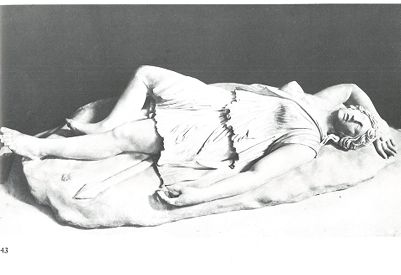

10) Roman copy of a Pergamese original, Dead Amazon. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples [5].38

Head of Adonis

11a) Peter Paul Rubens after an Antique coin, Alexander the Great as Jupiter Ammon, c. 1606, ink and bodycolour on card, 61 x 49 mm. Mrs Karl J. Reddy collection, Ephara, Pa.39

11b) Peter Paul Rubens (?) after a print by Paulus Pontius I after Peter Paul Rubens, after an Antique cameo (sardonyx), Germanicus Caesar, 1613–40, brush in brown and grey, pen in brown, with white oil on paper; contre-épreuve of an engraving by Paulus Pontius I, 80 x 60 mm (oval). RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-T-1934-4.40

11c) Peter Paul Rubens, Head of Alexander the Great, pen and brown ink over black chalk, washed, 59 x 50 mm. Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, III, 162 (second from below).41

11d) Peter Paul Rubens, Head of a Hellenistic Ruler, pen and brown ink, 33 x 31 mm. Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, III, 162 (bottom centre).42

11e) Peter Paul Rubens (?) and Jacob de Wit, Portrait of a Roman Emperor, probably Nero, red chalk, brush in red, 109 x 96 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-T-00-440 [6].43

Crouching female figures

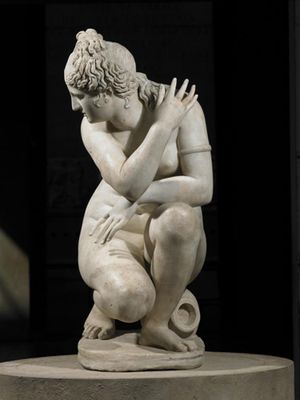

12a) Roman copy after a Hellenistic bronze statue, attributed to Doidalses of Bithynia, Crouching Venus, marble, h. 78 cm. Uffizi, Florence, 188.44

12b) Roman copy after a Hellenistic bronze statue, attributed to Doidalses of Bithynia, Crouching Venus (‘Lely’s Venus’), 125 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 69746, on loan to BM [7].45

12c) Roman copy after a Hellenistic bronze statue, attributed to Doidalses of Bithynia, Crouching Venus, Louvre, Paris.46

12d) Variation on the Crouching Venus by Doidalses of Bithynia, Roman, Crouching Venus with Turtle, marble, h. 128 cm. Prado, Madrid, 33E.47

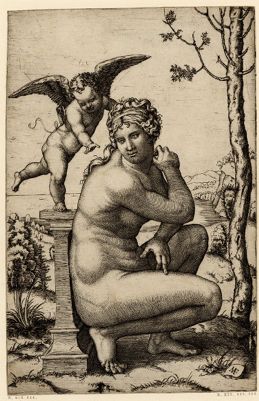

12e) Marcantonio Raimondi, Naked Venus crouching at her Bath, c. 1510–27, engraving, 223 x 146 mm. BM, London, H,2.68 [8].48

12f) Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel I, Diana and her Nymphs setting out for the Hunt, c. 1620, panel, 57 x 98 cm. Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris, no. 68.3.1.49

12g) Peter Paul Rubens, Study for Mary Magdalen, black chalk, heightened with white, 335 x 243 mm. BM, London, 1912,1214.5.50

12h) Jan Collaert after Peter Paul Rubens, title page for H. Rosweyde, ’t Vaders Boeck, Antwerp 1617. Royal Library, Brussels, III 6035 C.51

Boy with a goose

13a) Roman copy of a Hellenistic type by Boethos, early 2nd century BCE, Boy standing with a Goose, marble. Museo Nazionale delle Terme, Rome.52

13b) Rubens’s Cantoor (Willem Panneels) after Rubens, Three Studies of the Child embracing a Goose, inscribed dees drij kinnekens sijn goed van omtreck / ende hebbe dees oock gehaelt vant cantoor (these three children have a good silhouette; and I had fetched these too from the office), black, red and white chalk, pen and brown ink, 203 x 330 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, Rubens’s Cantoor, III, 23 [9].53

Other artist

14) Pieter Codde, Venus mourning Adonis, signed Pr. Codde, oil on panel, 31 x 32 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, 3150.54

DPG451

Peter Paul Rubens

Venus Lamenting Adonis, c. 1613-15

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG451

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Death of Adonis (with Venus, Cupid and the Three Graces), c. 1614

Jeruzalem (city, Israel), The Israel Museum, inv./cat.nr. B00.0735

2

Willem Panneels after Peter Paul Rubens

Death of Adonis

Copenhagen, SMK - The Royal Collection of Graphic Art, inv./cat.nr. Rubens'Cantoor IV.38.

3

studio of Peter Paul Rubens or Frans Snijders after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Greyhounds, c. 1612

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. 95

4

Anonymous, Roman

Adonis at the Hunt

marble, 177 cm high

Rome, Galleria Spada

5

Anonymous, Roman

Dead Amazon

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

6

school of Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob de Wit

Portrait of a Roman Emperor, probably Nero

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-00-440

7

Anonymous, Roman, 2nd century

Aphrodite or 'Crouching Venus'

marble 125 x 53 x 65 cm

Great Britain, The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 69746

8

Marcantonio Raimondi

Venus crouching against a pedestal

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. H,2.68

9

after Peter Paul Rubens

Three studies of a child with a goose, 17th century

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. Rubens Cantoor, III, 23

This is an almost monochrome sketch, or grisaille, with only some red and blue. The blue is used for the sky, and the red for drapery on the left, for the blood on the thigh of Adonis and on the ground in front of the dogs (one of them is licking the blood). After this modello a large painting was made, now in Jerusalem (Related works, no. 1a) [1], as Britton in 1813 already knew: at that time the prime version was in the collection of the famous London collector, patron and designer Thomas Hope (1769–1831).55 Possibly also a copy, now dismembered and formerly in France, was made after DPG451 (Related works, no. 1b). The dogs in the sketch are without doubt by Rubens. Those in the Jerusalem painting are attributed by some to Snijders.56 Robels in her œuvre catalogue of Snijders considers them not to be by him, and not by him the picture with three dogs in Brunswick (Related works, no. 7a) [3], which others also attribute to Snijders. The Brunswick dogs are related to the animals in the Jerusalem picture. The dog on the left is similar, but the dog on the right has its legs in a V-form, whereas in the Jerusalem picture they form an X. It is not unthinkable that Snijders was responsible for the Jerusalem dogs. In any case they were painted before the landscape.57 However in other Adonis scenes with dogs Rubens painted the animals himself, as in the Düsseldorf picture of c. 1610 (Related works, no. 7b).58 One of the dogs in the Brunswick picture appears in two paintings by Jan Wildens of 1624 and 1625 (Related works, nos 7d.I–II), where they seem to be painted by Wildens.59 It seems that stock figures in Rubens’s studio were freely used by painters with whom Rubens collaborated.

Today no one doubts the authenticity of DPG451,60 but in some 19th-century Dulwich catalogues it was called ‘School of Rubens’, and even ‘Vandyke’ by Denning in 1858, which is not surprising since even until 1900 the œuvres of the two most important Flemish 17th-century masters were not clearly defined.

Generally DPG451 is dated c. 1614, based on the smooth style of the Jerusalem picture. The mythological content of that picture is also similar to a number of scenes painted by Rubens between 1613 and 1615. Rubens had earlier depicted Adonis lamented by Venus, c. 1602 (Related works, nos 6a, b), but that scene is composed very differently: Adonis is semi-erect lying on his back, and Venus is to the right of him, standing uneasily, bent over to the left, with her head above his. Somewhat later Rubens produced three drawings on the theme, which are also not related to the Dulwich picture. While in DPG451 Adonis is lying on his back, roughly parallel to the horizontal edge of the picture, with his head on the left, his left leg raised and his right leg down, in the three drawings his body is upright, with his legs bent to the right and his head bent to the left. In two of them Venus, on the right, is holding his shoulders, while in one she holds his torso which is bent over to the left. In all three cases Adonis’s right arm is hanging down (Related works, nos 4a–c).

In comparison to the Jerusalem picture many of the figures in DPG451 are barely sketched in, and the setting is not complete, as usual in a Rubens modello. There are also some small compositional changes between the sketch and the finished painting: the nearer dog is in a different position, and while he is licking in DPG451 he appears to be merely sniffing in the Jerusalem painting; Cupid’s quiver is horizontal, and his arms are in a different position; Venus has been given a bracelet on her right upper arm; the Grace on the right no longer has hair in front of her eyes; and the landscape in the back and especially on the right is much more elaborated. The sketch shows Adonis wounded in the thigh, whereas in the finished painting he seems to be bleeding only from his groin (see below). Willem Panneels, who was left in charge of Rubens’s studio while he was away in Spain and London (1628–30), made a drawing after Venus lamenting Adonis which is clearly after DPG451 (or a very similar sketch) and not after the Jerusalem picture (Related works, no. 2) [2]. Small details in DPG451 (the licking dog, the hair of the Grace on the right-hand side, the posture of Cupid’s arms) indicate that DPG451 was probably Panneels’s model. That means that DPG451 (or another very similar sketch) was still available in Rubens’s studio for Panneels to copy.61 Panneels made an etching with a different scene of Venus lamenting Adonis (Related works, no. 3b) where Venus is related to a nymph in a Fall of Phaeton now in Frankfurt (Related works, no. 3a).

While the figure of Adonis can be found in other paintings attributed to Rubens, it is questionable whether they are not copies of this motif in DPG451 and the Jerusalem picture. The Reclining Youths that Jaffé attributed to Rubens was strongly doubted by Held in 1980 (Related works, nos 9a, b).62 Comparisons can be made with other scenes by Rubens that include reclining naked male bodies: Christian scenes with Cain and Abel, the Lamentation or Deposition of Christ, the Good Samaritan, St Sebastian, and mythological scenes with Prometheus, Hero and Leander, and Cephalus and Procris (Related works, no. 8c). The last scene by Rubens himself is especially similar: there a female figure is reclining while the male figure is bending over. In any case Rubens used the same motifs in both religious and mythological contexts, as in scenes where Christ becomes Prometheus (Related works, nos 8d.I–III), the Maries at the grave become weeping Graces (DPG451), and Venus becomes Mary Magdalen (Related works, no. 12g). Steinberg even suggests that ‘Rubens saw these scenes as akin to each other, perhaps even perceiving the lamentation over Adonis as a kind of prefiguration of the lamentation over Christ’.63 The composition of DPG451 has a strong sculptural quality, almost as if the figures are in bas-relief, and perfectly illustrates Rubens’s theories put forward in his De imitatione [antiquarum] statuorum.64 That is even more the case with two modelli of which we know that they were used for a silver basin and an ivory salt cellar (see under DPG264, Related works, nos 2a, Fig., and 2d.I, Fig.). In any case almost all the figures in DPG451 seem to be derived from Antique statues. The question is whether the audience was expected to recognize the Antique sources.

For the separate elements of the composition many sources have been pointed out. It is quite possible that for the position of the legs of Adonis (one stretched out and the other raised with bent knee) Rubens had looked at the statue of the Dead Amazon, then in the Palazzo Medici, later Madama, in Rome (Related works, no. 10) [5]. The figures of Venus and the Grace holding the cloth above Adonis both derive from the Hellenistic sculpture of a Crouching Venus, rising from the water, attributed to Doidalses of Bithynia, widely known through Roman copies, with different positions of Venus’s arms (Related works, nos 12a–d).65 It is possible that Rubens saw the version then in the Gonzaga collection in Mantua, now in the British Royal Collection on loan to the British Museum, the so-called ‘Lely’s Venus’ (Related works, no. 12b) [7].66 In DPG451 the Doidalses Venus is seen from the right and the Grace is seen frontally, but Venus’s arms are more or less hanging down, unlike any of the Doidalses Venuses. This Antique Venus, also know from a print by Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1480–1527/34; Related works, no. 12e) [8], was frequently used by Rubens, as already noted by Kieser in 1933.67 For the dogs Rubens (or was it Snijders?) could have looked at the Antique relief in the Spada Collection in Rome (Related works, no. 7e) [4]. The Cupid looks very much like the Antique sculpture of the Boy with a Goose, of which several copies exist and of which there is a study in Rubens’s Cantoor where the boy is seen from three sides (Related works, nos 13a, b) [9]. The profile of Adonis may be derived from an Antique coin, medal or cameo, rotated to 90 degrees (Related works, nos 11a–e) [6]. There is a parallel to the Grace to the right, with her hair hanging before her eyes, in the figure of a female hermit, St Eugenia, on a title page by Jan Collaert after a design by Rubens (Related works, no. 12h).

The story of Venus and Adonis is to be found in Ovid, Metamorphoses (X.717–23). Rubens depicted several scenes from this story: Venus who tries to prevent Adonis from going hunting (as in Related works, no. 7b), Adonis killed by the boar (as in the late hunting scene formerly in Madrid; Related works, nos 6a, b), and the scene as in DPG451, where Venus is lamenting Adonis.68 This scene is probably based not so much on Ovid as on a later version by Bion, the Lament for Adonis. There we find a description of the lament of the nymphs and Charites or Graces.69 We see Adonis, killed by a boar while hunting, being mourned by his lover Venus, accompanied by nymphs and Graces and Cupid. Held in 1980 noted that in Bion the Erotes (Cupids) break their bows, arrows and quivers. That is not happening here – or is Cupid lifting his quiver off his back, to take out the arrows for destruction? In Bion Adonis is wounded by the boar in his thigh (as in DPG451) and in Ovid in his groin (as apparently in the Jerusalem picture). We don’t know why Rubens changed that detail, or whether it has any meaning.

A sketch by the 17th-century Amsterdam artist Pieter Codde (1599–1678), now in the Hermitage, St Petersburg, of the Death of Adonis, has recently been associated with the composition of DPG451 and the picture in Jerusalem (Related works, no. 14).70

DPG451

Peter Paul Rubens

Venus Lamenting Adonis, c. 1613-15

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG451

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Death of Adonis (with Venus, Cupid and the Three Graces), c. 1614

Jeruzalem (city, Israel), The Israel Museum, inv./cat.nr. B00.0735

3

studio of Peter Paul Rubens or Frans Snijders after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Greyhounds, c. 1612

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. 95

2

Willem Panneels after Peter Paul Rubens

Death of Adonis

Copenhagen, SMK - The Royal Collection of Graphic Art, inv./cat.nr. Rubens'Cantoor IV.38.

5

Anonymous, Roman

Dead Amazon

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

7

Anonymous, Roman, 2nd century

Aphrodite or 'Crouching Venus'

marble 125 x 53 x 65 cm

Great Britain, The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 69746

8

Marcantonio Raimondi

Venus crouching against a pedestal

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. H,2.68

4

Anonymous, Roman

Adonis at the Hunt

marble, 177 cm high

Rome, Galleria Spada

9

after Peter Paul Rubens

Three studies of a child with a goose, 17th century

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. Rubens Cantoor, III, 23

6

school of Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob de Wit

Portrait of a Roman Emperor, probably Nero

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-00-440

Notes

1 Denucé 1932, p. 169.

2 GPID (11 June 2014); ‘Rubens; The death of Adonis, Venus, Cupid, and attendants, a most wonderful composition, being the sketch for the famous picture painted by that master at Madrid, and the Escurial.’ Is one of the late hunting scenes meant, see Related works, no. 6a–b? Those however depict a somewhat earlier scene of the story of Adonis (we see him being killed). Moreover those pictures were in the Alcázar Palace in Madrid, not in the Escorial, as far as we know.

3 GPID (17 June 2014).

4 Cook 1914 proposed that DPG451 might be No. 92 in Desenfans 1802, but the description of that picture, which was attributed to Anthony van Dyck, is: ‘On his [Adonis’s] right, is the goddess dressed in red, with a light yellow drapery floating in the air; she is kneeling, her hands and eyes raised towards heaven, supplicating the gods to restore her unfortunate lover to life.’ This does not match DPG451, and moreover the picture is described as being on canvas.

5 ‘751. The Death of Adonis […] and the landscape is by the free pencil of Wildens. […] A picture of this subject was put up to sale in the collection of Mr. Bryan, 1798, and knocked down at 1407l. Now in the collection of Thomas Hope, Esq. A sketch for the preceding picture is in the Dulwich Gallery. […] Panneels has etched a print, representing Venus kneeling by the side of Adonis […] her car drawn by swans is on one side, and the dogs of the huntsman on the other.’ See Related works, no. 3b.

6 ‘The composition is precisely that of the great picture of Rubens, now in Mr. Hope’s collection.’

7 ‘a sketch; Van Dyck. A preparation interesting to students and others, curious as to so fine a painter’s manner of proceeding.’

8 No. 5. Mort d’Adonis. Quatre Nymphes désolées l´entourent et decouvrent son corps inanimé. Cupidon lui-même s´attendrit. Un chien lèche le sang qui sort de la plaie, & était dégoûtant. Un autre chien regarde son maître. Jolie esquisse à peine colorée. (No. 5. Death of Adonis. Four sad Nymphs surround him and uncover his lifeless body. Cupid himself is moved. A dog licks the blood that comes out of the wound; it was disgusting. Another dog looks at his master. Nice sketch, barely coloured.)

9 La galerie de Dulwich Collège possède un panneau, mentionné comme une esquisse de ce tableau, où Vénus n’est accompagnée que d’une nymphe […] (Dulwich College Gallery has a panel, said to be a sketch for this painting, where Venus is accompanied by only one nymph [?]).

10 ‘an exquisite, little known and unpublished sketch for it in Dulwich’.

11 Tyers 2014, pp. 40–42.

12 RKD, no. 294323: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294323 (July 3, 2019); Prov.: Brants family, The Hague; according to Maës (2005, pp. 61, 67 (note 65)) the picture was in an Antwerp collection (where Jacques-Louis David could have seen it, 1781–2); sale Michael Bryan, London, Peter Coxe, 19 May 1798 (Lugt 5764), lot 57; sold or bought in, £1,417.10; Dorking, Deepdene, Thomas Hope collection, by 1813; by descent; Christie’s, 20 July 1917, lot 117; bt Gooden and Fox, £131 5s 0d for Lord Leverhulme; Lord Leverhulme; by descent; Christie’s, 24 March 1961; bt Duits and Co.; New York, Mr and Mrs Saul P. Steinberg collection. According to Jaffé (1967, p. 5) the landscape in the Jerusalem picture is not painted by Wildens, nor are the dogs by Snijders. Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 182, fig. 6, under DPG451; Steinberg 2012; Maës 2005, pp. 61–2 (fig. 5); Jaffé 1989, p. 196, no. 254.

13 Formerly Mme S. Blondel collection, Château de la Belle-Allée, Chaingy (1898–1905); Lucien Rollin collection, Paris, 1940; Nathan Katz sale, Paris, Galerie Charpentier, 7 Dec. 1951, lot 40. Probably dismembered after this date. According to Held, a fragment was sold on 19 Nov. 1956: Held 1980, i, p. 361 (who does not give a judgement). See also Jaffé 1967, pp. 3–4 (copy); Evers 1943, pp. 121–9, figs 27–9 (Rubens); Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), pp. 189–91, no. 696 (Rubens).

14 RKD, no. 295161: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295161. 13, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 182, fig. 7, under DPG451; Steinberg 2012, p. 24 (fig. in colour), 25 (note 10); not in Garff & De la Fuente Pedersen 1988; Jaffé 1967, pp. 5, 7, 11 (fig.), 13 (note 21).

15 RKD, no. 249903: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/249903 (July 3, 2019); Tieze 2009, pp. 392–400, no. 1121 (Nymphs and River God); Balis 1993 (Nymphs and River god; part of The Fall of Phaeton); Jaffé 1982, p. 62; Held 1980, i, p. 329, no. 241, ii, pl. 449 (The Three Heliades and the River Po).

16 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Sheepshanks-5360 (Aug. 2, 2020). Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 209.

17 RKD, no. 294831: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294831 (Aug. 22, 2019); see also https://search.museumplantinmoretus.be/details/collect/275651 (Aug. 22, 2019); Jaffé 1977, p. 65R, fig. 213; Evers 1943, fig. 35; Delen 1938, i, pp. 65–6, no. 193, ii, pl. XXXVII.

18 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1895-0915-1064 (Aug. 2, 2020); Jaffé & McGrath 2005, pp. 68–9, no. 14; K. Renger in Denk, Paul & Renger 2001, pp. 250–51, no. Z 19; Held 1986, p. 92, no. 57, fig. 56; Renger 1983, p. 206; Rowlands 1977, pp. 64, no. 61, 104 (col. pl. 61); Held 1959, i, pp. 102–3, no. 22, ii, pl. 23; Evers 1943, fig. 37.

19 Steinberg 2012, p. 58; translation of the Latin inscription in Rowlands 1977, p. 64, no. 60. See also Jaffé & McGrath 2005, pp. 68–9, no. 15; Rosenthal 2005, pp. 147–9, fig. 53; Held 1986, p. 92, no. 58, fig. 57; Evers 1943, fig. 36.

20 Rosenthal 2005, p. 117, fig. 39.

21 RKD, no. 251283: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/251283 (Aug. 23, 2019); see also https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/19749 (Aug. 23, 2019); Balis 1986, pp. 249–50, no. 24a; fig. 119; Held 1980, i, pp. 305, 307, no. 222.

22 Robels 1989, pp. 390–91, no. 296; Balis 1986, pp. 247–9, no. 24. Under this number ten copies (also in tapestry) are mentioned. For the eight hunting scenes that Rubens and Snijders made for the King of Spain after 1639 see ibid., pp. 218–33.

23 RKD, no. 295116: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295116 (Aug. 31, 2019); Gatenbröcker 2004, p. 85 (fig. 6; Frans Snijders); Klessmann 2003, pp. 94–5, 163 (fig.), no. 95 (Frans Snijders); Robels 1989, pp. 493–4, no. A SK 4 (not Frans Snijders; studio of Rubens); see also Adler 1980, pp. 38, 85 (note 208), 103 under G 42–3 (Related works, nos 7d.I–II).

24 RKD, no. 242770: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/242770 (Aug. 23, 2019); Baumgärtel & Bürger 2005, pp. 184–7, no. 136.

25 RKD, no. 5521: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/5521 (Aug. 23, 2019); Buvelot 2004, pp. 272–3, no. 254.

26 Marx 2005–6, ii (2006), p. 588, no. 2134 (gal. no. 1133; the dimensions given are wrong (194 x 202 cm)); N. Gritsay in Gritsay & Babina 2008, p. 430, under no. 529 (Related works, no. 7d.II); Adler 1980, pp. 37–8, 85 (note 206), 103 (G 42), 172 (figs 65–6).

27 N. Gritsay in Gritsay & Babina 2008, pp. 429–30, no. 529; Adler 1980, pp. 37, 85 (note 206), 103–4 (G 43), 173 (figs 67–8).

28 RKD, no. 295163: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295163 (Aug. 31, 2019); Rosen 2008, pp. 96–7 (fig. 4).

29 Renger 1983, p. 205, fig. 1.

30 RKD, no. 17117: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/17117 (Aug. 23, 2019); Renger 1983, p. 205, fig. 2; Mielke & Winner 1977, pp. 135–7 (Nachtrag; fig.)

31 Steinberg 2012, p. 54 (fig. in colour); Burchard & D’Hulst 1963, i, pp. 138–40, fig. 84 recto, ii, fig. 84 recto.

32 RKD, no. 229856: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/229856 (Aug. 23, 2019). See also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/la-muerte-de-abel/?no_cache=1 (Aug. 23, 2019); Jonckheere 2013, pp. 134–5, fig. 132.

33 Jonckheere 2007, pp. 123–4, 237, no. A103.

34 RKD, no. 271956: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/271956 (July, 6, 2019); see also http://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/5112 (July 6, 2019); http://museu.ms/collection/object/132073/abel-slain-by-cain?pUnitId=428 (Aug. 14, 2020); Jonckheere 2007, pp. 123–4, 347 (fig. 17); Jonckheere 2013, p. 193, cat. no. 34.

35 RKD, no. 49969: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/49969 (July 5, 2019); see also https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/104468.html?mulR=513320086|8 (July 6, 2020); Bikker 2004–5, pp. 47–8, 53, fig. 2; Scott, Dugan & Paschetto 1994, p. 91.

36 According to Held (1980, i, p. 362) this is a pastiche (‘The very fact that its support is canvas, most unusual for a Rubens sketch, would cast doubt on its authenticity’), but according to Jaffé (1967, pp. 6 (fig.), 7, 10–11) it is a ‘highly finished study’ (p. 7). http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=1982488 (July 6, 2019) as cited by Steinberg 2012, p. 26 (note 14). On the Christie’s website the amount paid is given (Sale 9558, 26 Janote 2001, New York, Rockefeller Plaza) – $88,125, which shows that nobody at the sale believed this was an authentic Rubens sketch.

37 RKD, no. 28788: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/28788 (Aug. 23, 2019); Neumeister 2009, pp. 272–5; Jaffé & McGrath 2005, pp. 188–9, no. 88; Renger & Denk 2002, pp. 288–91, no. 326; Jaffé 1989, p. 199, no. 273 (1614–15); D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 150–54, no. 47, fig. 103.

38 RKD, no. 295162: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295162 (Aug. 31, 2019); Bober & Rubinstein 1986, pp.179–80, no. 143, fig. 143.

39 Jaffé 1977, pp. 83R, 117 (note 81), fig. 311.

40 RKD, no. 273998: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/273998 (July 6, 2019) – together with 107g (Solon, Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), p. 202, iii (1995), fig. 331). See also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collect.69188 (July 9, 2019); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), p. 201, no. 170f, iii (1995), fig. 332; Jaffé 1977, pp. 84L, 117 (note 84), fig. 310 (c. 1621).

41 RKD, no. 274030: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/274030 (Aug, 23, 2019); Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), p. 209, no. 178, iii (1995), fig. 348.

42 Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), p. 209, no. 179, iii (1995), fig. 349.

43 RKD, no. 295125: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295125 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collect.68154 (July 11, 2019).

44 F. Paolucci in Sframeli 2003, pp. 31 (fig.), 68–9, no. 1; Haskell & Penny 1982, pp. 321–3, no. 86, fig. 171.

45 RKD, no. 295126: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295126 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also https://www.rct.uk/collection/69746/aphrodite-or-crouching-venus (Aug. 24, 2019); Bober & Rubinstein (1986, pp. 62–3, no. 18, fig. 18).

46 Baudouin 1977, pp. 111, 112 (fig. 9).

47 B. Cacciotti in Borea & Gasparri 2000, ii, pp. 420–21, no. 17.

48 RKD, no. 295127: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295127 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_H-2-68 (Aug. 2, 2020).

49 RKD, no. 49996: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/49996 (Aug. 24, 2019) A. van Suchtelen in Woollett & Van Suchtelen 2006, pp. 108–15, no. 10 (with no. 11, its pendant, see RKD, no. 49997: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/49997 (Aug. 24, 2019)); Jaffé 1989, p. 282, no. 771; Balis 1986, pp. 57 (note 38), 182, 184 (note 30), fig. 5; Müller Hofstede 1968. This picture is, like The Feast of Achelous (see under DPG43, Related works, no. 4c.I; note 33), depicted in the painting by Jan Brueghel II, An Allegory on the Art of Painting, c. 1625, oil on copper, 47 x 75 cm. Private collection, The Netherlands; see E. Hermens in Komanecky & Bowron 1999, pp. 158–61, no. 9.

50 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1912-1214-5 (Aug. 2, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 183, fig. 9, under DPG451; Rowlands 1977, pp. 71 (no. 73), 102 (col. pl. 73).

51 The kneeling female hermit at the bottom left is St Eugenia. Judson & Van de Velde 1977, i, p. 199, no. 42, ii, fig. 146.

52 Van der Meulen 1994–5, i (1994), p. 49, ii (1994), p. 87, iii (1995), fig. 133 (copy in the Cesi collection in the 17th century); she sees a relation with the Jerusalem picture (Related works, no. 1a; Fig.); Bober & Rubinstein 1986, pp. 233–4, no. 200, fig. 200; here the version in the Glyptothek, Munich, is illustrated; Baudouin 1977, pp. 111, 112 (fig. 10).

53 RKD, no. 272901: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/272901 (Aug. 24, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 182, fig. 8, under DPG451; Van der Meulen 1994–5, i (1994), p. 49, ii (1994), pp. 87–8, no. 70 (copy), iii (1995), fig. 134; Garff & De la Fuente Pedersen 1988, i, p. 98, no. 110, ii, pl. 112. NB: cantoor in gehaelt vant cantoor probably refers to cantoor as a room, and not as a cupboard (the literal meaning of the word): see Huvenne 1993a, pp. 16–17.

54 RKD, no. 58484: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/58484 (Aug. 25, 2014); Sluijter 2015, pp. 305 (fig. V–58), 307.

55 For Hope as a designer see Watkin & Hewat-Jaboor 2008; as a collector Niemeijer 1982. For a portrait of Thomas’s grandfather, Archibald Hope, in Dulwich by Gerard Sanders (1737), DPG577, see RKD, no. 278062: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/278062 (July 11, 2019).

56 As in Rosen 2008, pp. 91–9, and as mentioned by Robels 1989, p. 493; Jaffé 1967 strongly objects to collaboration with any other painter.

57 Michiel Jonker observation in Jerusalem: see note of 13 June 2012 (DPG451 file).

58 That dog, head on, with its legs in the form of a V, appears in a painting attributed to (or made after) Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaerts, RKD, no. 103083: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/103083 (July 11, 2019).

59 N. Gritsay in Gritsay & Babina 2008, p. 430.

60 However Ludwig Burchard wrote on a photograph of DPG451 (in RUB, LB no. 635/1 file): Kopie nach echter (verschollener) Rubensskizze. Eine zweite Kopie / Nachzeichnung in Kopenhagen (Copy of an authentic (lost) Rubens sketch. A second copy / drawn copy in Copenhagen). Perhaps that is why DPG451, according to us one of the best in Dulwich, had not come to the attention of the curators of the last Rubens sketch exhibition: see Lammertse & Vergara 2018.

61 However it does not appear in the 1640 inventory that was made after Rubens’s death, published in Belkin & Healy 2004, pp. 328–33 and Muller 1989, pp. 91–146.

62 Held 1980, i, p. 362. See also Related works, no. 9a, and note 36 above.

63 Steinberg 2012, p. 31.

64 See Muller 1982 for Rubens’s art theory in general. De imitatione statuarum records Rubens’s views on the role of sculpture in the training of painters and its significance to painting in general. See Herremans 2019, pp. 46–65. Because of the link with sculpture it does not seem probable that Rubens was inspired by Michelangelo’s Tityus now in the Royal Collection (RCIN 912771; see https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/1/collection/912771/recto-the-punishment-of-tityus-verso-the-risen-christ (Dec. 18, 2020), as suggested on the DPG website (17 Dec. 2020). Moreover, the rotated position of Tityus’ body is quite different from that of the calmly reclining Adonis.

65 See Bober & Rubinstein 1986, pp. 59–65, nos 12–20 for the types of Venus. They offer only three images of crouching Venuses (figs 18, 19 and 19a).

66 Steinberg 2012, pp. 28 (fig.), 30; see also under DPG165, Related works, no. 5; Fig. (Venus Frigida). But according to Jaffé (1977, pp. 79R–80L, 116 (notes 11, 15) it was another sculpture, in the Cesi collection, Rome, on which Rubens based his crouching figures.

67 Kieser 1933, p. 119.

68 See Healy 2001b, pp. 64–7.

69 English translations in Steinberg 2012, pp. 38 (Bion), 39 (Ovid); a German translation in Evers 1943, pp. 126–7. It was Evers and not Held in 1980 who first saw the relation to the Bion text, as Held himself faithfully says (p. 361).

70 Sluijter 2015, pp. 307, 440 (note 132), fig. V–58. Although Codde’s composition in which with many hands are depicted can also be related to DPG127, according to Eric Jan Sluijter it was at the time in an Amsterdam collection (in conversation, Aug. 2014).