Peter Paul Rubens DPG148

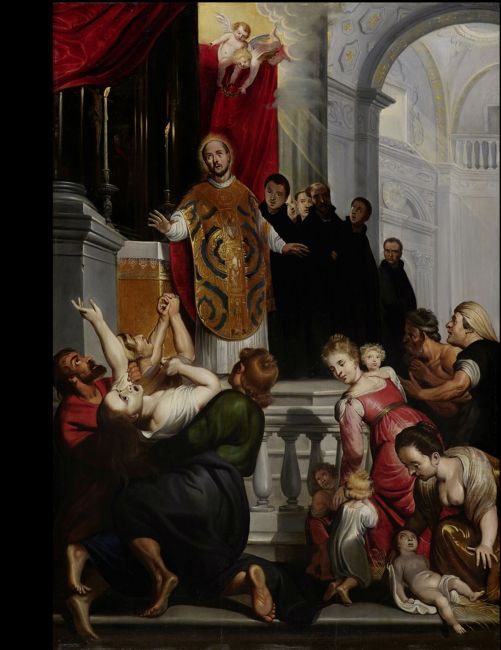

DPG148 –Miracles of the Blessed Ignatius of Loyola1

c. 1618–19 (or earlier?); oak panel, 73.7 x 50.2 cm

PROVENANCE

?c. 1619 (or earlier?) for Marcello or Nicolò Pallavicini, who commissioned the altarpiece for Sant’Ambrogio (now the Chiesa del Gesù/Santi Ambrogio e Andrea), Genoa; probably not Genoa, Palazzo of Pietro Gentile, Third Room, 1768–88 (see under References); ?Rubempré sale, Brussels, 11 April 1765, lot 69 (Saint Ignace guérissant un possédé, 29 x 18 p. [78 x 46 cm], panel), fl. 300, bt Berthel;2 ?Greenwood sale, 19 March 1791 (Lugt 4691), Rubens, ‘St. Ignatius casting out the evil spirits’ (no dimensions); transaction unknown; not Benjamin van der Gucht sale, Christie’s, 12 March 1796 (Lugt 5420), lot 75, bt Sir Francis Bourgeois (Related works, no. 6a); not Desenfans 1802, ii, p.19, no. 83 (as on canvas, and ‘capital’);3 ?bt by J. Irvine for W. Buchanan, April/May 1803;4 ?Brigstocke 1982, W. Buchanan to J. Irvine, letters 3 June 1803–18 Oct. 1805;5 Insurance 1804, no. 21 (‘St. Ignatius exorcising – Rubens; £300’); Britton 1813, p. 2, no. 11 (‘Small parlour; no. 11; Group of figures in a Temple – frantic woman – sick children – a Priest or Saint. Sk[etch] Pan[el] Rubens’; 3'6" x 2'6").

REFERENCES

?Brusco 1768, p. 34;6 ?Brusco 1773, p. 46; ?Ratti 1780, i, p. 121;7 ?Brusco 1781, pp. 35–6;8 ?Brusco 1788, p. 59;9 Cat. 1817, p. 10, no. 176 (‘SECOND ROOM – East side; Saint Ignatius of Loyala [sic] healing the Sick; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 388, no. 176 (An Historical Sketch); Cat. 1820, p. 10, no. 176 (Ignatius of Loyala [sic] healing the Sick; Rubens); Buchanan 1824, ii, pp. 103, 129, 133–5; Cat. 1830, no. 235 (A Study After Rubens); Smith 1829–42, ix (1842), p. 337, no. 347 (St Ignatius healing the Sick and Possessed; mentioned by Buchanan);10 Denning 1858, no. 235;11 not in Denning 1859; Sparkes 1876, p. 153, no. 235 (A Study; attributed to P. P. Rubens), Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 143, no. 235 (under old copies after Rubens; A Saint saying Mass); Rooses 1886–92, ii (1888), p. 293, no. 455bis (sketch in the Pietro Gentile collection, Genoa, in 1802); Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 38, no. 148 (A Saint blessing the Sick; after Rubens); Cook 1914, pp. 88–9, no. 148; Oldenbourg 1921, pp. 202, 462, under no. 202 (DPG148 is an old original); Oldenbourg 1922, p. 14 (Rubens); Cook 1926, p. 83, no. 148 (after Rubens); Cat. 1953, p. 35 (school of Rubens); Jaffé 1966a, p. 413 (note 5); Jaffé 1969b, pp. 528–30 (fig. 1; Rubens); Müller Hofstede 1969, pp. 190–94 (fig. 2), 231–3 (notes 12–26) (Rubens, c. 1618–19); Smith 1969, pp. 57 (fig. 36), 59, note 50 (Rubens); Berger 1972, p. 476 (note 28) (Rubens); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 80–82, under no. 116a (DPG148 is a copy; arguing against Rubens’s authorship based on the quality and the provenance); Jaffé 1977, p. 102; Biavati 1977, pp. 236 (fig. 88), 237; Murray 1980a, pp. 115–16 (St Ignatius Loyola exorcising; attributed to Rubens); Murray 1980b, p. 25; Held 1980, i, pp. 457 (under no. 329), 566–8, no. 411 (Rubens, c. 1619), ii, pl. 400; Lecaldano 1980, i, p. 152, no. 400 (Rubens, 1619); Logan 1981, pp. 514, 517; Brigstocke 1982, W. Buchanan to J. Irvine letters (3 June 1803–18 Oct. 1805; see Provenance); Bodart 1985, p. 170, no. 374a; Jaffé 1988b, p. 527; Jaffé 1989, p. 245, no. 516 (1618–19); Brigstocke 1992, p. 828; Jaffé 1997, pp. 62 (fig. 48), 63; Beresford 1998, p. 210; Boccardo & Orlando 2004, pp. 32 (no. I.27), 58 (fig. 1; A. Orlando), under no. 2 (Related works, no. 1; Fig.; Rubens); Tyers 2014, pp. 28–30; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 183–7, 212; Bober, Boccardo & Boggero 2020, pp. 106–7, no. 7; RKD, no. 253849: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253849 (Aug. 17, 2020).

EXHIBITIONS

Genoa 1977–8, pp. 236–7, fig. 88, under no. 6 (G. Frabetti); Frankfurt 1992, pp. 63–4, pl. 13 (and detail), no. 10 (M. Jaffé); p. 623 (A. Peltz); Genoa 2001, pp. 137–8, no. III.54; Washington/Rome 2020–21, pp. 106–7, no. 7.

TECHNICAL NOTES

The two-member oak panel is approximately 0.6 cm thick and bevelled at the edges, with a 5 cm square oak inset in the top left corner. It has a vertical grain and a slight warp, which have caused some vertical cracking. The paint layer is in good condition, though worn and abraded in some areas, particularly in the figures in black. There are some old restored vertical cracks at the bottom edge.

Evidence of other forms beneath can be read by the naked eye in the area to the right of the saint’s head and above, to the left of the putti. The X-ray [1] reveals that there are figures to be read upside down, on a larger scale than the present composition, looking up to an unidentifiable scene: a bearded man seen from behind, profil perdu, looks up to the right. Just above him is an outline of a hooded figure, hands together in prayer, while in the bottom right corner along the edge of the painting is another hooded figure facing left but with head tilted looking up and away from the viewer. The scale of the figures, the apparent truncating of both the bearded man below the waist and of the second figure at the edge, as well as the weighting of the composition to the right, suggests that the panel was cut down once the original project was abandoned.

Dendrochronology has linked the left hand board to one in Christ with the Brazen Serpent, attributed to Rubens and studio, which was sold at Sotheby’s in 2014;12 dating gives a terminus post quem for these panels of c. 1607.13

Previous recorded treatment: 1952–5 and 1959–60, with Dr Hell; 1982, surface cleaned, examined (including X-radiograph of painting), losses filled and blistering areas consolidated, retouched, varnished, National Maritime Museum, E. Hamilton-Eddy.

RELATED WORKS

1a) Prime version (the completed altarpiece): Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracles of St Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1612–20, canvas, 442 x 287 cm. Il Gesú/SS. Ambrogio e Andrea, Genoa [2].14

1b) (sketch) Peter Paul Rubens, St Ignatius of Loyola (?) curing one possessed, present whereabouts unknown (Phillips, London, 3 May 1823, lot 73: ‘Rubens. Our Saviour curing one possessed of an evil spirit, a sketch for the famous picture in the church of the Annunciation at Genoa – this celebrated study was in the possession of the Gentile family at Genoa’).15

1c) copy after DPG148 (? or after 1b), panel, 104 x 72 cm. Museen der Stadt Bamberg, 393D [3].16

1d) David Wilkie after Peter Paul Rubens (1a), The Miracles of St Ignatius of Loyola, drawing in album, 54 pp., dimensions of album 265 x 210 mm, NGS, Edinburgh, D.4981.17

2a) (modello for 2b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracles of St Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1615–16, oak panel, 105.5 x 74 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 530 [4].18

2b) (altarpiece for the Antwerp Jesuit Church) Peter Paul Rubens and studio, The Miracles of St Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1617–18, canvas, 535 x 395 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 517 [5].19

2c) (in reverse) Marinus Robyn van der Goes after 2b, St Ignatius of Loyola cures a Possessed Man and Woman, 1630–39, engraving, 575 × 450 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP–P–OB–67.925.20

3a) (modello for 3b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracles of St Francis Xavier, c. 1616–17, panel, 104.5 x 72.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 528.21

3b. (altarpiece for the Antwerp Jesuit Church) Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracles of St Francis Xavier, c. 1617–18, canvas, 535 x 395 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 519.

Other pictures by Rubens

4) (for the high altar) Peter Paul Rubens, Circumcision, 1605, canvas, 400 x 225 cm. Il Gesú/Santi Ambrogio e Andrea, Genoa.22

5) Peter Paul Rubens, Marchese Nicolò Pallavicini, 1604, canvas, 105 x 92 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (previously on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge).23

Details

The Blessed Ignatius, since 1622 St Ignatius

6a) Peter Paul Rubens, ‘St. Ignatius attired in his priestly habit, in the attitude of ecstacy and inspired devotion; Rubens has treated this subject in a grand stile, the colouring truly harmonious, and painted with a spirited and flowing pencil’, present whereabouts unknown (Benjamin van der Gucht sale, Christie’s, 12 March 1796 (Lugt 5420), lot 75; bt Sir Francis Bourgeois, £39.18.24

6b) Peter Paul Rubens, St Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1620–22, canvas, 223.5 x 138.4 cm. Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena, M.1975.03.P.25

6c) Adriaen Collaert after Juan de Mesa, Five Scenes of the Life of the Blessed Ignatius in Barcelona (part of Vita beati patris Ignatii Loyolae, Antwerp 1610, no. 7 of 15 prints), Latin inscriptions, engraving, 262 × 368 mm (sheet). RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-P-1963-287.26

The washerwoman

7a) Adriaen Collaert after Juan de Mesa, Three Scenes from the Life of the Blessed Ignatius in Spain (part of Vita beati patris Ignatii Loyolae, Antwerp 1610, no. 9 of 15 prints), Latin inscriptions, engraving, 266 × 368 mm (sheet). RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-P-1963-288.27

7b) Cornelis Galle I, The Miracle of the Washerwoman, engraving (fig. 48 of Vita beati P. Ignatii Loiolae, Rome 1609). Biblioteca Instituti Historici S. I., Rome.28

The possessed woman

8a) Peter Paul Rubens, The Martyrdom of two Saints, pen and brown ink on grey paper, 348 x 324 mm. BvB, Rotterdam, MB 5002.29

8b) (modello) Peter Paul Rubens, Roman Catholic Austria, attacked by its Enemies, 1620–22, panel, 51 x 66.5 cm. Musée Fabre, Montpellier, 836.4.52.30

8c) (modello) Peter Paul Rubens, Miracles of St Francis of Paola, c. 1627–8, panel, 110.5 × 79.4 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, 91.PB.50.31

8d) Roman, Medea Sarcophagus, marble, h 65 cm. Antikenmuseum, Basel, 217.32

8e) Peter Paul Rubens after an Antique cameo, A Dancing Satyr, c. 1600–1608, pen and brown ink, 54 x 37 mm. BM, London, Oo,9.20.e.33

8f) Anthony van Dyck, The Arrest of a Man, part of a Study for the Road to Cavalry, black chalk, with pen and brown ink, 154 x 202 mm (sight measurement) (sheet 19 verso and 20 recto in the Italian sketchbook). BM. 1957,1214.207.19v and 20r.34

8g) (attributed to) Artus Quellinus I, Frenzy, c. 1660, sandstone, 295 × 75 x 75 cm. RM, Amsterdam, BK-AM-38.35

Confusion in provenance

9) After Peter Paul Rubens, An Allegory showing the Effects of War (‘The Horrors of War’), paper on canvas, 47.6 x 76 cm. NG, London, NG279.36

Compositions by other artists

10) Giovanni Balducci, The Investiture of Carloman, fresco. San Giovanni de´ Fiorentini, Rome.37

11) Caravaggio, Madonna of the Rosary, c. 1601, 364.5 x 249.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 147.38

DPG148

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, 1618-1619

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG148

1

X-ray of DPG148

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, 1612-1620

Genoa, Il Gesù (Genua)

3

after Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of the Blessed Ignatius of Loyala, c. 1790-1850

Bamberg, Historisches Museum (Bamberg), inv./cat.nr. 393D

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1618

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 530

5

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1617-1618

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 517

Although bought and displayed as an original by Rubens, in 1880 Richter and Sparkes suggested that DPG148 was a copy – which is understandable due to the presence of copious overpainting, probably by Sir Francis Bourgeois, and extensive damage. The overpainting was removed by Dr Hell in the early 1960s (although some overpaint seems to remain on the small child in the centre of the composition and on the women on the right), leading both Michael Jaffé and Müller Hofstede in 1969 to accept it as an original, as Ludwig Burchard had done (his notes say Echt Rubens (nur im schlimmem Zustand) – a real Rubens (but in bad condition)).39 Since then Rubens’s authorship has remained the general consensus. Vlieghe, however, has continued to doubt the picture, on the grounds of its inferior quality (understandable given its poor condition) and its provenance – or rather lack of it (see below).40 Recent X-ray analysis (asked for in Held 1980) has revealed the presence of underlying figures in a different composition (upside down in relation to the surface composition), which seems to support Rubens’s authorship [1]. The figures under the paint layer are characteristic of Rubens; so far it has been impossible to prove with any certainty an association with this or other Rubens compositions.

In the 1610s Rubens completed two related altarpieces dedicated to the Blessed Ignatius, the 16th-century Spaniard of Basque origin who founded the Society of Jesus. One was for the Jesuit Church in Antwerp; the Society of Jesus was abolished in 1773, and it has been in Vienna since 1776 (Related works, no. 2b) [5]. The other, still in situ, is the altarpiece of the family chapel of Nicolò Pallavicini (1563–1619) in the north transept of the church of the Gesù, SS. Ambrogio e Andrea, in Genoa, a Jesuit church (Related works, no. 1a) [2]. Both pictures were meant to support and accelerate the process of Ignatius’s canonization, which was achieved in 1622. In both cases a sketch has survived. DPG148 is the modello for the Genoese altarpiece. The composition is a small-scale treatment of the altarpiece of the Antwerp Jesuits, for which there is a sketch in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (Related works, no. 2a) [4], which also possesses the altarpiece. The picture was not Rubens’s first work for the church in Genoa: in 1604–5 he produced a Circumcision (still in situ) for the high altar (Related works, no. 4), possibly through the action of Nicolò Pallavicini, signore di Mornese and banker to the Duke of Mantua. His brother, Padre Marcello Pallavicini, financed the construction of the church, and thought that the high altar should be decorated with a painting depicting the Mystery of the Circumcision. Rubens and Nicolò Pallavicini had known each other since 1604 when the artist painted a three-quarter length portrait of him (formerly in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Related works, no. 5); Rubens named his son, born on 23 March 1618, Nicholas after his Genoese friend. On 16 March 1612 Nicolò Pallavicini decided to spend 2,000 Genoese lire annually for the decoration and upkeep of his private chapel in Santi Ambrogio e Andrea; his brother, Padre Marcello, was to have control of its decoration throughout his life (he was to die in 1624 or 1625), and Nicolò’s son Antonio would have that role after Marcello’s death. It is unclear whether Nicolò saw Rubens’s modello before he died in 1619. Although we do not know anything about the commission, it seems possible that in 1612 Nicolò Pallavicini had already asked Rubens to make an altarpiece for the family chapel in the church. Peltz seems to be certain that both brothers commissioned the altarpiece c. 1619, and Rubens sent the modello to Genoa. According to Devisscher and Vlieghe, however, it was Nicolò alone who gave Rubens the commission.41 In any case the finished canvas arrived in Genoa in 1620.

As can be seen by comparison between DPG148 and the altarpiece in Genoa [2], Rubens reversed the direction in which the Blessed Ignatius faces, deprived him of his halo, added further figures, and modified the poses of the crowd that gathers to watch the miracles. The position of the sick (or dead?) child below right has also been reversed, and the positions of the washerwoman and the old man on the right have been transposed. Michael Jaffé in 1969 argued that Ignatius’s pose might have been modified due to objections (presumably from Padre Marcello) to the way the saint looks – which could interpreted as a Christ-like glance at the possessed girl: in the final altarpiece he looks upwards with his hands extended and open in supplication. Several scholars, starting with Smith in 1830 and 1842,42 pointed out that the scene does not depict a single moment but is a ‘summary’ of the saint’s miracles. Rubens seems to have used the Life of the Blessed Ignatius of Loyola by the Spanish Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneira (first edn Naples 1572), of which in 1610 an Antwerp version was published with prints by Adriaen Collaert (c. 1560–1618) (Related works, nos 6c, 7a).43 Smith in 1969 noted that the old woman on the right who holds in her left hand something like a piece of cloth may be the washerwoman whose withered arm was restored after doing the saint’s laundry. The scene was included in an engraving by Cornelis Galle I (1576–1650) for the Vita Ignatii of 1609, to which Rubens also contributed (Related works, no. 7b).44

Müller Hofstede and Held suggested that Rubens, in reaching his final composition, is likely to have been influenced by Caravaggio’s Madonna of the Rosary (Related works, no. 11), which had arrived in Antwerp c. 1618 to be installed in St Paul’s Church. This comparison is dismissed by Vlieghe.45

There has been considerable debate regarding the sequencing of the Antwerp and Genoa pictures. Held argued that the preparatory work for the Antwerp altarpiece took place in 1617 and that it was probably finished in 1618, therefore preceding the Genoa altarpiece; Jaffé initially had the opposite opinion but subsequently changed his mind. It is also possible that work on the Genoa picture may have been carried out in fits and starts over several years, as was often the case for a private commission by a friend. That could mean that work on the two Ignatius altarpieces overlapped.

When we compare the compositions of the altarpieces for Genoa and Antwerp (now Vienna) there are a number of major differences. The architecture in the Genoa composition is angled to the right, in the Antwerp composition to the left.46 In the Genoa version both Ignatius’s hands are stretched out, while in the Antwerp version his left hand is resting on the altar. There is one possessed girl in DPG148 and the Genoa altarpiece; the Antwerp version includes a possessed man.47 There are more figures in the Antwerp altarpiece, not surprisingly since it is about 1 m higher and 1 m wider than the Genoa picture.

As usual with Rubens, motifs are found elsewhere as well. In a painting in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (Related works, no. 6b) the full-length figure of the Blessed (or perhaps already Saint)48 Ignatius holding a book has the same pose as in DPG148, but his glance is shifted significantly upwards, as in the Genoa picture; he has a halo, which he lacks in the Genoa picture.49 The possessed girl is a motif that could have been derived from Antique objects such as a cameo and a sarcophagus, which Rubens used again for instance in later compositions in Montpellier and the Getty Museum (Related works, nos 8a–f). A famous statue of Frenzy was made for the Amsterdam Dolhuys (madhouse), probably by the southern Netherlandish sculptor Artus Quellinus (Related works, no. 8g), who must have known Rubens’s painting. The woman with three children, symbolizing Charity, also appears in Rubens’s work, such as the altarpiece for St Bavo in Ghent (see DPG40A–B, Related works, no. 7b).

The provenance of DPG148 is uncertain between Rubens and the Desenfans Insurance list of 1804. We do not know how many studies Rubens made for the Genoa altarpiece (in general he made at least two studies, a bozzetto and a modello: see for instance under DPG125), and whether he sent all of them to the Pallavicini or kept one or more in his studio. It is certain that since 1768 at least one of the sketches was in the third room of the Palazzo Spinola di San Luca-Gentile in Genoa, probably from the Pallavicini family. Until now several authors assumed that the Rubens sketch acquired by Buchanan in 1803 in Genoa came from the Pietro Gentile collection, and that it was shortly afterwards purchased by Desenfans. However the Buchanan letters, written between 1802 and 1805, seem to show that he acquired a different Rubens sketch in 1803 (now in the National Gallery; Related works, no. 9) and that he finally succeeded in purchasing the Gentile picture of the Blessed Ignatius (Related works, no. 1b) in 1805. It appeared in a London auction in 1823, since when there is no trace. We have to look for the provenance of Desenfans’ St Ignatius in 18th-century sale catalogues where several pictures of St Ignatius by Rubens are mentioned, such as one in Brussels in 1765 and one in London in 1791. In any case DPG148 features in Desenfans’ Insurance list of 1804.

A small copy in the Städtischen Kunstsammlungen Bamberg, which seems to date from around 1800, was recently brought to my attention (Related works, no. 1c) [3].50 It is not after the prime version in Genoa. The position of Ignatius looks more like the one in the Dulwich picture; the man in the foreground holding the frantic woman is dressed in green, as in the Dulwich modello, not red as in Genoa; the two standing children in the middle and the baby lying down are different. In Genoa the baby’s head is to the right, whereas in the other two pictures it is to the left. However there are also differences between the Bamberg picture and the modello in Dulwich. In general the figures and architecture there are so elaborate that it seems unlikely the copyist saw the painting in Dulwich. And while it is appealing to think that the Bamberg picture is a copy of the lost sketch from Genoa (Related works, no.1b) that does not seem likely: Rubens usually made a very general bozzetto first and then a more elaborated modello (see under DPG125). DPG148 is such an elaborated modello. Rubens did not make sketches more detailed than this. It is thus more likely that the artist of the Bamberg picture saw a painting that was a different version of Rubens’s composition, probably from Rubens’s workshop. However, nothing is known of a third large-scale Jesuit altarpiece that might have been the model for the Bamberg copyist.51

DPG148

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, 1618-1619

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG148

1

X-ray of DPG148

5

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1617-1618

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 517

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, 1612-1620

Genoa, Il Gesù (Genua)

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1618

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 530

3

after Peter Paul Rubens

Miracles of the Blessed Ignatius of Loyala, c. 1790-1850

Bamberg, Historisches Museum (Bamberg), inv./cat.nr. 393D

Notes

1 When this modello was made, and the altarpiece was completed, Ignatius was only beatified; he became a saint in 1622.

2 Note in RUB, LB no. 496 file (Nota’s Le Roy). Not in GPID (17 Oct. 2020); there, however, is the following: ?Langford sale, 10 April 1778 (Lugt 2830a), Rubens, ‘St. Ignatius de Loyola, the founder of the order of the Jesuits, filled with the Holy Ghost, which is seen descending over him in the form of a fiery tongue, by the power of faith expels devils. This is truly a miracle of the painter, as well as of the saint. It is, indeed, a most expressive sketch for an altar-piece, well known to those who have travelled in the Low Countries. Purchased at Brussels from the cabinet of the Prince de Beaupré’; transaction unknown. This description does not seem to agree with DPG148.

3 See note 25 (Van der Gucht sale and Desenfans 1802).

4 Buchanan 1824, ii, pp. 101–6, letters from D. Irvine to W. Buchanan: ‘Genoa, Sept. 25, 1802 […] no. 2 – [in a palazzo in Genoa] Finished sketch of St. Ignatius bringing to life a Boy, &c. The large picture in the Jesuits’ church here. A charming thing.’; pp. 128–32: ‘Genoa, 30th April, 1803 […] I have hopes of doing something effectual with Pietro Gentile […] You will remember he possesses the Judith by Guido and the sketch of St. Ignatius (not St. Paul) by Rubens […] Three cabinet pictures […] One is a sketch by Rubens of an allegorical subject, the large picture of which was in the Pitti palace at Florence […] not of his most brilliant colouring (as his sketches seldom are), yet it is very harmonious and certainly genuine, though, in point of value or consequence, it cannot be compared with the St. Ignatius. The second is the study, by Guido, of a picture at Rome representing the Trinity […]’; pp. 132–3: 2d May. The answers of the Doge and Gentile both have been unfavourable; p. 133: ‘Of the pictures mentioned in the letter […] were afterwards acquired for Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Campernowne, as were likewise the fine Rubens and Guido, finished studies, therein described’ (NB: it is not clear which of the two mentioned Rubens studies was acquired, the St Ignatius or the Allegory; however in Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 186, it is assumed (as in Martin 1970, p. 232, and Brigstocke 1982, p. 81) that in 1803 the Allegory now after Rubens, NG279, London, was acquired by Buchanan and Campernowne; Related works, no. 9); pp. 134–5, letter D. Irvine to W. Buchanan:‘Genoa, 16th May, 1803. […] Before going to the country I concluded a bargain for the two sketches by Rubens and Guido mentioned in my last, at 8000 livres, or nearly £285 sterling’. According to Vlieghe (1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 80–81, no. 116a) DPG148 cannot be the work by Rubens purchased for Buchanan in 1803 from the Gentile family in Genoa since that picture was on the London art market in 1823 (see Related works, no. 1b). See RKD, no. 253846: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253846 (Aug. 28, 2019). However Martin had previously determined (see above) that the copy after Rubens’s Horrors of War, bought for the National Gallery in 1856 (NG279), was the painting bought in Genoa in 1803: see Martin 1970, pp. 230–3 (provenance on p. 232 and notes 21–6 on p. 233). That painting had, according to Martin, not been part of the Gentile collection.

5 Letter no. 12, 3 June 1803, p. 79; this letter probably refers to the altarpiece in S. Ambrogio, and not to the sketch, since Buchanan writes: ‘The St. Ignatius I would go to £2000 or 2500’. That is too much for a sketch. Letter no. 14, 23 July 1803, p. 93 (under ‘the pictures of the Cabinet size […] as […] the [Rubens] St. Ignatius sketch’); letter no. 17, 17 Oct. 1803, p. 107 (under pictures that ‘may be acquired’); letter no. 84, 25 Jan. 1805, p. 370 (‘I have only made one reservation in favour of myself, which is the small Rubens of St. Ignatius at Genoa, should we ever obtain it’); letter no. 85, 7 Feb. 1805, p. 375 (‘I also reserved to myself the small Ignatius Rubens if that is ever acquired, which I am very anxious for, although you go to a very handsome price for it, say £500’); letter no. 88, 26 March 1805, pp. 385–6 (‘I trust Sigr Wilson will not require the Rubens Sketch [St. Ignatius] and Guido at Genoa. My Stipulation with Campernowne and a friend of his Mr. Carr, who has now also a share in the Speculation, was that that sketch was to be entirely my property. Of course if both Guido and Rubens are acquired you must not burden the Rubens too much with the price paid for both. Since yours of the 23d February you will have received my subsequent letter which puts matters on a better footing, and I trust you would not let slip the opportunity of securing the Rubens sketch.’) However in the previous letter (no. 87) another Rubens sketch is discussed, according to Brigstocke the Allegory showing the Effects of War, now in the NG, London (NG279; see the preceding note). It is possible that in the next letter Buchanan still writes about that and not about St Ignatius. Letter no. 90, 3 May 1805, p. 398 (‘that the only picture I reserved a claim exclusively to, upon my own account, should be the small Rubens of St. Ignatius if you ever acquired that picture’); letter no. 95, 23 July 1805, pp. 417–18 (‘I have no objection to what extent I do in such purchases as […] the Rubens sketch […] and again call your attention not to lose sight of […] the Rubens sketch at Genoa [St Ignatius]’); letter no. 98 (?), 4 Oct. 1805, p. 431(‘I am glad you have got another Rubens Sketch – the print I have not yet been able to find – pray where was the Great Altar Piece?’ [Buchanan probably refers here to the print by Van der Goes, Related works, no. 2c]); letter no. 99, 18 Oct. 1805, p. 436 (‘I hope to hear of its being on account, of the St. Ignatius Sketch [Rubens] etc.’). It is clear from these letters that in 1805 a sketch by Rubens for the Blessed Ignatius was still in Genoa (from the Gentile collection; Related works, no. 1b), which could not have been DPG148, since that picture was already in Desenfans collection in 1804 (Insurance 1804, no. 21).

6 (In the third room of the Palazzo of Pietro Gentile) Un ebauche [sic] du Tableau de Saint Ignace, par Rubens l’original est aux Iésuites (a sketch of the picture of St Ignatius by Rubens, the original is in the Jesuit Church).

7 (Palazzo del Sig. Pietro Gentile; Terzo Salotto) S. Ignazio operante miracoli, sbozzo de la tavola d’Altare che vedesi nella Chiesa di S. Ambrogio, del Rubens. (Palace of Pietro Gentile; Third Room; St Ignatius working miracles, sketch of the altarpiece that can be seen in the Church of S. Ambrogio, by Rubens).

8 See the preceding note.

9 ibid.

10 ‘This is probably the original sketch for the altar-piece at Genoa.’

11 ‘Rubens; Not in the Gallery – indeed it is all but destroyed. It came to Dulwich in a terrible damaged state. Mr Desenfans called it “St Ignatius Exorcising” & valued it in 1804 for Insurance at £ 300. Was in my room. S.P.D. 1859.’

12 Sotheby’s, New York, 30 Jan. 2014, lot 25; Tyers 2014, pp. 28–30.

13 Tyers 2014, p. 28.

14 RKD, no. 253843: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253843 (July 2, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 184, fig. 10, under DPG148; Boccardo & Orlando 2004, p. 30, no. I.14, pp. 58–9, no. 2 (A. Orlando); Barnes, Boccardo, Di Fabio & Tagliaferro 1997, pp. 204–5 (P. Boccardo); Jaffé 1989, p. 245, no. 517; Biavati 1977, pp. 229–37, no. 6, fig. 86; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 78–80, no. 116; Tacchi Venturi 1929, pp. 33–4, no. XXIX, fig. XXIX; Brusco 1788, p. 37 (the same text is in Brusco 1792, p. 37); Ratti 1780, pp. 65–6; Brusco 1768, p. 15.

15 Not in GPID (5 July 2014); Held (1980, i, p. 567) pointed out that there are obvious mistakes in the description (‘Our Saviour’ for St Ignatius and ‘the church of the Annunciation’ for Sant’Ambrogio), but he assumes that the composition is related to the altarpiece for Sant’Ambrogio. It may be that the picture sold in London in 1823 was another step in the production of the finished altarpiece, and it would seem likely that such a picture existed: not only was it Rubens’s usual practice to produce first a bozzetto and then a sketch for his clients, but the Pallavicini family would no doubt have wanted to see the changes he had made to the composition before letting Rubens complete the work for Sant’Ambrogio. See also note 5 for the Ignatius sketch that was acquired by Buchanan in 1805. According to Vlieghe (see note 4) the picture at auction in 1823 had been acquired from the Gentile family in 1803. But the picture that was bought in 1803 in Genoa (and that ended up in the National Gallery) did not come from the Gentile family: see notes 4 and 5 above.

16 Email from Stefan Bartilla to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 28 Oct. 2020, with a draft of the entry for the forthcoming catalogue of Dutch and Flemish pictures in the Städtischen Kunstsammlungen (City Museums) Bamberg (by Thomas Fusenig and Stefan Bartilla) and a photograph (DPG148 file). See RKD, no. 298864: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/298864 (Nov. 11, 2020).

17 RKD, no. 253845: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253845 (July 3, 2019), Bulletin 1972, fig. 8 (leaflet in RUB, LB no. 496/1 file); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 78, under no. 116 (Related works, no. 1; copy); Thompson, Brigstocke & Thomson 1972, p. 27, for Wilkie’s travels to Genoa in the 1820s.

18 NB: previously known under inv. no. 312; RKD, no. 253830: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253830 (July 2, 2019); see also www.khm.at/de/object/d1dc3a8270/ (July 2, 2019); Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 210, 213, 215–20, no. 46 (W. Prohaska); Ferino-Pagden, Prohaska & Schütz 1991, p. 103, pl. 400; Jaffé 1989, p. 237, no. 478; Held 1980, i, pp. 564–6, no. 410, ii, pl. 398; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 75–6, no. 115a, fig. 41; E. Haverkamp-Begemann in Ebbinge Wubben, Fierens & Haverkamp Begemann 1953, p. 53, no. 25, pl. 27.

19 NB: previously known under inv. no. 313; RKD, no. 107841: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/107841 (July 2, 2019); see also www.khm.at/de/object/4462bf0ddb/ (July 2, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 184, fig. 11, under DPG148; Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 211–20, no. 47; Ferino-Pagden, Prohaska & Schütz 1991, p. 103, pl. 400; Jaffé 1989, p. 237, no. 480; Held 1980, i, pp. 564–6, under no. 410; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 73–4, no. 115, fig. 40.

20 RKD, no. 253839: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253839 (July 2, 2019); see also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.337069 (July 2, 2019); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 77, under no. 115c (drawing in the Louvre), copy. It is not clear why Vlieghe says that this print was made after a drawing now in the Louvre, when on the print it says that Rubens had painted (pinxit) the original; or was the drawing in the Louvre an intermediary stage? In Hollstein (1954, p. 170, no. 9) it says that the print was made after the picture now in Vienna.

21 RKD, no. 57985: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/57985 (July 2, 2019); see also www.khm.at/de/object/806beafe15/ (July 2, 2019); Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 215–21, no. 48 (W. Prohaska); Schröder & Widauer 2004, pp. 304–9, no. 64 (H. Widauer); Ferino-Pagden, Prohaska & Schütz 1991, p. 103, pl. 401; Jaffé 1989, p. 237, no. 479; Held 1980, i, p. 560–62, no. 408, ii, pl. 397; E. Haverkamp-Begemann in Ebbinge Wubben, Fierens & Haverkamp Begemann 1953, pp. 52–3, no. 24, pl. 26.

22 RKD, no. 253482: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253482 (July 2, 2019); see also www.khm.at/de/object/c7af0926b2/ (July 2, 2019); Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 214–21, no. 49 (W. Prohaska); Ferino-Pagden, Prohaska & Schütz 1991, p. 104, pl. 401; Jaffé 1989, p. 237, no. 481.

23 RKD, no. 106260: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106260 (July 2, 2019); Devisscher & Vlieghe 2014, i, pp. 102–5, no. 21; according to them it was Marcello who gave the commission, but it cannot be ruled out that Nicolò was also involved, as Rooses first suggested in 1886 (Rooses 1886–92, i (1886), p. 202), ibid., p. 104; Jaffé 1989, p. 54, no. 54; Jaffé 1988b, pp. 525–6, fig. 37. For the drawn and painted studies for this altarpiece see Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 60–62, no. 3 (the modello in Vienna); Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 100–103, fig. 56, under no. 17 (the drawing in Vienna); Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 171–7, fig. 1, under nos 15–16 (the drawing and the modello in Vienna); Held 1980, i, pp. 458–9, under no. 331, ii, pl. 326 (the modello in Vienna).

24 Jaffé 1989, p. 153, no. 37.

25 GPID (17 Oct. 2020); Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 68–71, no. 113. NB: according to Vlieghe (p. 71), its pair, no. 114, St Francis Xavier, was no. 83 in Desenfans 1802. Although that picture is said to depict St Ignatius, Vlieghe asserts that it is the picture that was later in the possession of Francis Ingram Seymour-Conway, 2nd Marquess of Hertford; sale 20 May 1938; destroyed by fire, 1940. Desenfans 1802, pp. 19–20: ‘St. Ignatius […] We present in this, one of the most capital performances of that great master, which he executed for the church of the Jesuits at Antwerp, where it remained ’till the suppression of their order.’ Desenfans does not give a description of this picture, only that it is on canvas and that it is capital. We do not know whether it was like the Norton Simon picture (Related works, no. 6b). It could not be the picture of St Ignatius that was made for the Jesuit Church in Antwerp (Related works, no. 2b; Fig.), since in 1776 that picture went directly from the church to the Imperial Collection in Vienna, where it is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

26 RKD, no. 253792: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253792 (July 2, 2019); see also https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/M.1975.03.P (July 2, 2019); Jaffé 1989, p. 186, no. 203 (c. 1613); König-Nordhoff 1982, pp. 221–2, fig. 176; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 68–71, no. 113, fig. 36. The pendant of St Francis Xavier (ibid., pp. 71–2, no. 114; fig. 37) was destroyed in 1940. This picture was once in the collection of the Earl of Warwick: see also König-Nordhoff 1982, pp. 221–2, fig. 177. In the Brukenthal museum there are copies: ibid., figs 172–3.

27 http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collect.96817 (July 3, 2019); Diels & Leesberg 2005–6, iv (2005), pp. 176, 179 (fig.), no. 968; König-Nordhoff 1982, p. 266, no. 7, fig. 69. The five scenes are as follows: in the upper left corner Ignatius prays for the soul of a suicide; on the left he is abused by young people; in the upper centre he gets into a trance during a prayer in the house of Juan Pascual and starts to float; on the right he glows while listening to a sermon; and also on the right he appears after his death to his friend Juan Pascual. See also Tacchi Venturi 1929, p. 23, no. XIII, fig. XIII.

28 http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collect.96818 (Sept. 11, 2014); Diels & Leesberg 2005–6, iv (2005), pp. 177, 180 (fig.), no. 969; König-Nordhoff 1982, p. 266, no. 9, fig. 71. The three scenes, during his journey through Spain to visit his hometown, Azpeitia, are: on the left he is begging in his home town; in the background he preaches to a large crowd; on the right he heals the arm of a washerwoman. See also Tacchi Venturi 1929, pp. 24–5, no. XV, fig. XV.

29 Smith 1969, pp. 58 (fig. 37), 59, note 51.

30 Meij & De Haan 2001, pp. 103–5, no. 16; Burchard & D’Hulst 1963, i, pp. 145–8, no. 88 (The Stoning of St Stephen), ii, fig. 88.

31 RKD, no. 257147: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/257147 (July 3, 2019); Büttner & Heinen 2004, pp. 155–7, no. 16 (U. Heinen); Buvelot, Hilaire & Zeder 1998, pp. 164–5, no. 45 (O. Zeder); Jaffé 1989, p. 264, no. 664; Held 1980, i, pp. 532–3, no. 394, ii, pl. 385 (A religious allegory); Foucart & Lacambre 1977, pp. 180–81, no. 133 (P. Durey; Scène religieuse allégorique).

32 RKD, no. 40256: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/40256 (July 3, 2019); see also http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=960 (July 3, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 167–9, no. 51 (c. 1627–8); Woollett & Naumann 1995 (under 1990); Jaffé 1989, pp. 304–5, no. 905; Held 1980, i, pp. 554–60, no. 407, ii, pl. 396; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), pp. 24–6, no. 103c, fig. 3.

33 On each of the friezes of this sarcophagus we see a running female figure, head bent back, with her hands raised, as in The Death of the Bride, see Schmidt 1968, pp. 27–9, figs 1, 14 (1), 32 (1); see also 26 (1), 28 (1), 32 (2) and 32 (3).

34 RKD, no. 274055: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/274055 (July 3, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Oo-9-20-e (Aug. 2, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 186, fig. 13, under DPG148; Van der Meulen 1994–5, ii (1994), pp. 211–12, no. 183, iii (1995), fig. 353; Rowlands 1977, p. 99, no. 138e.

35 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1957-1214-207-19 (verso) and https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1957-1214-207-20 (recto) (both Aug. 2, 2020); Adriani 1965, p. 15, p. 19v and 20r, figs 19v–20r; Adriani 1940, pp. 36–7, nos 19v and 20r; figs 19v and 20r.

36 http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collectie.24785 (July 3, 2019). The statue originally stood in the garden of the Dolhuys (madhouse), the municipal institution for the mentally ill. A lunatic is peering out on each of the four sides of the pedestal. Scholten 2010, p. 54–5, fig. 61.

37 RKD, no. 197424: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197424 (Nov. 14, 2020); see also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/after-peter-paul-rubens-the-horrors-of-war (Nov. 14, 2020). Martin 1970, pp. 230–33, no. 279. This is the picture that was acquired in Genoa in 1803: see Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 186, Brigstocke 1982, p. 81, and Martin 1970, p. 232. See above, note 4.

38 Smith 1969, fig. 2.

39 RKD, no. 292666: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292666 (Nov. 17, 2020).

40 L. Burchard in note in RUB, LB no. 496/1 file, about DPG148.

41 Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 80, no. 116a. Under ‘Provenance’ he assumes that the sketch for sale in London in 1823 (now lost; Related works, no. 1b) was acquired in Genoa in 1803 from the Gentile collection. However in 1803 a different picture was purchased in Genoa, and not from the Gentile collection; that picture is now in the NG, London (Related works, no. 9). See above, notes 4 and 5.

42 A. Peltz, in Schleier 1992, p. 623; Bober, Boccardo & Boggero 2020, p. 106 (first Nicolò, after his death Marcello); see also Devisscher & Vlieghe 2014, p. 104; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 79.

43 Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 19, ix (1842), p. 337.

44 Smith 1969, p. 51 and note 28.

45 Rubens alledgedly contributed to W. Kilian, Vita Sanctii Ignatii Leiolae, societatis Iesu fundatoria [s.l. 1609 and 1622]: see König-Nordholt 1982, pp. 309–19. His compositions were engraved by an artist called Barbé; except for three titlepages, see figs 399–400, 411–12, 423, 429–32, 433–6, 437–40, 441–3, 447, 449–52, 453–6, 457, 462, 464, 466, 468, 472, 474, 477, 479, 482, 484–5, 520, 525. See also Held 1972.

46 Müller Hofstede 1969; Held 1980, i, p. 568; Vlieghe 1972–3, ii (1973), p. 79.

47 Lewine 1963 argues that for the architecture in the Antwerp version Rubens might have looked at the fresco by Balducci in Rome (Related works, no. 10).

48 Which influenced Van Dyck: see Martin 1983b, p. 41, figs 9–11.

49 The date of this picture is not certain. Some say that it was already made in Italy, so before or in 1608, but Vlieghe 1972–3 (ii (1973), pp. 70–71) suggests that this picture is related to the canonization of Ignatius of Loyola and Franciscus Xavier on 12 March 1622.

50 In the scene to the right in the print by Adriaen Collaert (Related works, no. 6c) the Blessed Ignatius is shown with a nimbus, listening to a sermon.

51 See note 16 above. With many thanks to Stefan Bartilla, whose critical comments in emails from 28 Oct. to 12 Nov. 2020 (DPG148 file) have helped to clarify the argument about the Bamberg picture.

52 Might the model have been a small-scale (or large-scale?) composition by one of the pupils or collaborators in Rubens’s studio or in its circle?