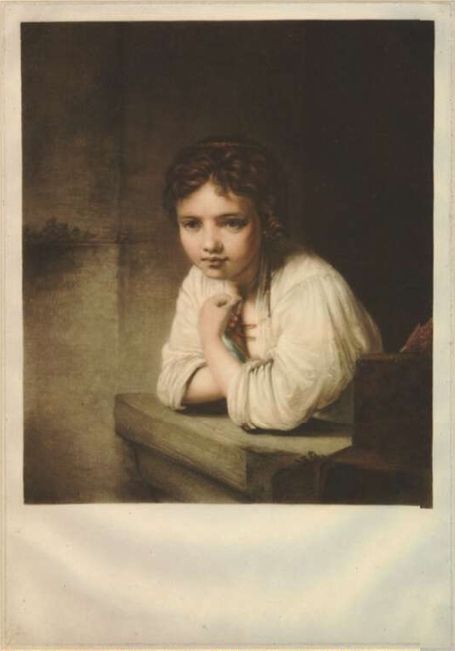

Rembrandt DPG163

DPG163 – Girl at a Window

or: Girl leaning on a Stone Pedestal (formerly La Servante (The Serving-Maid) / La Crasseuse (The Slattern))

1645; canvas, 81.6 x 66 cm, arched at the top

Signed and dated lower right Rembrandt ft . 1645

PROVENANCE

1) Roger de Piles, Paris, probably bought in Amsterdam in 1693, and brought to Paris in 1697;1 Roger de Piles inventory, 15 April 1709 (in the antichambre: 5 tableaux de toile, 1 représentant Van Dick, la Servante de Rembrant, […] dans leur bordure de bois doré, 300 l[ivres]’ (5 pictures on canvas, 1 depicting Van Dick, Rembrandt's serving maid […] in their frames of gilded wood, 300 French pounds).2

2) Adolphe Saint-Vincent Duvivier, Paris.3

3) Charles Jean-Baptiste Fleuriau, Comte de Morville and Seigneur d’Armenonville, Paris, inventory, 3 March 1732: Deux têtes de Rembrandt, valued at 800 livres, and Govert Flinck’s Flora (Related works, no. 1), which was probably acquired in The Hague between 1718 and 1720.4

4) Henry, Comte d’Hoym, Paris (acquired after 3 March 1732): inventory, June 1732, p. 31, nos 420 and 421: Deux tableaux représentant l’un la Crasseuse de Rembrandt avec son pendant, tous deux dans leurs bordures riches (Two paintings, one depicting Rembrandt's Slattern, with its pendant [Govert Flinck’s Flora], both in their rich frames);5 inventory, 1737, nos 82 and 83: Une Flore, une Crasseuse, sur bois avec bordure, 400 l[ivres]6 (A Flora, a Slattern, on panel with frame, 400 French pounds).

5) Louis-Auguste Angran, Vicomte de Fonspertuis, sale, Edmé-François Gersaint, Paris, 4 March 1748 (Lugt 682), lot 435: Il représente une jeune fille, espèce de Cuisinière, d’une phisionomie assez picquante, qui a les deux coudes appuyés sur une Table. On l’appelle, entre les Curieux, La Crasseuse de Rimbrant (It depicts a girl, a sort of cook, with a rather titillating appearance, who has both elbows resting on a table. It is known among connaisseurs as Rimbrant’s The Slattern [La Crasseuse]).7 Bought by Augustin Blondel de Gagny for 2,001 or 2,750 livres for nos 435 and 434 (with Govert Flinck’s Flora).8

6) Augustin Blondel de Gagny sale, Paris (Pierre Remy), 10 Dec. 1776 (Lugt 2616), lot 70;9 bought by Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun for 6,000 French francs pour Langleterre (for England; copy NG, London). In another copy: Recedé sur le Champ à un Anglois qui lui a donné 20 Louis de bénefice. Il avoit couté cher (Sold on the spot to an Englishman who gave him 20 louis d’or extra. It had been expensive).10

7) ?Desenfans sale, anonymous auction house, London, 8 April 1786 (Lugt 4022), lot 390: ‘Rembrandt; Dutch Woman; on canvas; 2'9" h x 2'5"’ (includes the frame); sold or bt in, £10.10.11 Insurance 1804, no. 88 (‘A Girl – Rembrandt’, £500).

8) Bequeathed to Bourgeois in 1807; Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 26, no. 258 (‘Small Drawing Room contd / no. 11, Head of a Girl looking out of a window – C[anvas] Rembrandt’; 4'6" x 3'3").

REFERENCES

De Piles 1708, pp. 10–11;12 De Piles 1715, p. 423;13 Gersaint 1747, pp. 198–202, no. 435 (see under Provenance); Descamps, ii, 1754, p. 97;14 Rémy 1776, p. 25, no. 70; Cat. 1817, p. 11, no. 177 (‘CENTRE ROOM – South Side; A Girl looking from a Window; Rembrandt’); Haydon 1817, p. 388, no. 177;15 Cat. 1820, p. 11, no. 177 (A Girl looking from a Window; Rembrandt); Patmore 1824a, p. 198;16 Patmore 1824b, pp. 55–6, no. 176;17 Hazlitt 1824, pp. 36–7;18 Cat. 1830, p. 10, no. 206 (A Girl at a Window; Rembrandt); Cat. 1831–3, p. 10, no. 206 (A Girl at a Window; Rembrandt [in the margin: Hubberish (?) and 1 stripe in the front margin and 1 behind]); Passavant 1836/1978, i, p. 62;19 Smith 1829–42, vii (1836), pp. 75, no. 178 (A Peasant Girl);20 Jameson 1842, ii, p. 476, no. 206;21 Hazlitt 1843, p. 29 (about the same text as Hazlitt 1824); Houssaye 1848, ii, p. 163; Waagen 1854, ii, p. 342;22 Blanc 1857–8, i (1857), p. 335;23 Denning 1858, no. 206;24 not in Denning 1859; Thoré-Bürger 1860, pp. 42–3;25 Vosmaer 1868, pp. 199, 471;26 Sparkes 1876, pp. 135–6, no. 206 (Rembrandt’s Servant-maid); Clément de Ris 1877, pp. 354–5; Vosmaer 1877, pp. 263, 538; Richter & Sparkes 1880, pp. 126–7, no. 206;27 Dutuit 1885, p. 31 (âgée d’environ douze ans – aged about twelve); Richter & Sparkes 1892, pp. 42–3, no. 163; Michel 1893, pp. 303, 555; Michel 1894 (Engl. edn), i, p. 303, ii, p. 234 (as from R. Hibbert collection); Bode & Hofstede de Groot 1897–1906, iv (1900), pp. 193–4, no. 300, vii, 1902, p. 212, no. 300; Campbell 1903, p. 242;28 Valentiner 1905, pp. 41–4 (Hendrickje Stoffels); Richter & Sparkes 1905, p. 43, no. 163; Rosenberg 1906, pp. 220 (fig.), 400; Rosenberg & Valentiner 1909, p. 320; Thompson 1910–12, i (1910), p. 7, fig. IV; Cook 1914, p. 101, no. 163; HdG, vi, 1915, p. 162, no. 327 (provenance mentioned under no. 330 [the picture now in Stockholm, Related works, no. 2c], p. 163 belongs to no. 327; Engl. edn 1916, pp. 188–9); Mirot 1924, p. 64; Cook 1926, p. 95, no. 163; Whitley 1928a, p. 253; Bredius 1935, no. 368; Gerson 1942/1983, p. 68; Benesch 1947a, p. 32, under no. 143 (Related works, no. 1b); Rosenberg 1948, i, pp. 51–2, ii, fig. 77; Waterhouse 1950, p. 12, no. 21; Cat. 1953, p. 33, no. 163; Paintings 1954, pp. 1, 60 (+ cover); Slive 1953, pp. 129, 131; Rosenberg 1964, pp. 89–91, fig. 77; Teyssèdre 1965, pp. 398, 518; Bauch 1966, p. 14, no. 268; Gerson 1968, p. 70 (de Piles anecdote refers to the picture in Woburn Abbey, Related works, no. 2e, pp. 330–31, 497, no. 228); Haak 1969, pp. 190–91 (fig. 311), 332; Bredius & Gerson 1969, p. 579, no. 368; Benesch 1973, iv, p. 186 (under no. 700; drawing, Related works, no. 1b); Cailleux 1975, pp. 290, 302–3 (note 18; the first to say that the 1747 and 1776 sale catalogue entries can only refer to DPG163); Koslow 1975, pp. 429–30 (fig. 28); Haak 1976, pp. 27, 29 (fig.); Clark 1978, p. 83 (fig. 85); Kris & Kurtz 1979, pp. 8–10, 63; Strauss & Van der Meulen 1979, p. 244; Blunt 1980, p. 445 (note 110); Brown 1980, i, pp. 24, 25 (fig.), ii, 28 (fig.), no. 239; Murray 1980a, p. 101, no. 163; Murray 1980b, p. 22; O’Neill 1981, p. 131; Kitson 1982 (see Kitson 1992); White, Alexander & D’Oench 1983, pp. 44, under no. 81 (Say mezzotint, 1814, Related works, no. 6e), 109, no. 58 (in list of works in 18th-century England); Schwartz 1985, p. 242 (fig. 267); Brème 1985, p. 148, under no. 108 (Jean-Baptiste Santerre; Related works, no. 4a.I) [8]; H. Oursel in Oursel, Schnapper & Foucart 1985, p. 140, under no. 100 (Jean Raoux; Related works, no. 4c); Guillaud 1986, p. 331, no. 386; Tümpel 1986, pp. 263 (fig.), 407, no. 149; Foucart 1988, pp. 80–81 (fig.), under Jan Victors (Related works, no. 2a); Waterfield 1988, pp. 10, 12, 15, 32–4, 36–7, 43, 48; Dukelskaya & Renne 1990, pp. 163–4, under no. 101; Bockemühl 1991, p. 54 (fig.); Cabanne 1991, p. 150, no. 7 (fig.); J. Kelch in Brown, Kelch & Van Thiel 1991, p. 232, under no. 36 (Related works, no Ic.II); C. Brown in Brown, Kelch & Van Thiel 1991, pp. 352–3 (fig. 72a), under no. 72 (Related works, no. 2f); Kitson 1992, pp. 72–3, no. 21; Roscam Abbing 1992; Miller 1992, p. 745 (fig. XVIII); Ingamells 1992, p. 37 (note 3), under P74 (Ferdinand Bol, The Toper); Cavalli-Björkman 1992, p. 196, under no. 57; Slatkes 1992, p. 313, no. 202; Liedtke 1992b; Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993; Brown 1993; Cavalli-Björkman 1993c; Roscam Abbing 1993a; Sumner 1993; Plender 1993; Roscam Abbing 1993b; Schneider 1993, p. 59 (fig. 3); Cavalli-Björkman 1993b; Wheelock 1993, pp. 142, 145 (fig. 2), 147, 149, 155 (note 16); Sumner 1994b; Nash 1995, pp. 185–6 (gold beads/chain); Postle 1995, pp. 104, 106, 326 (notes 36–7); Sonnenburg 1995, pp. 2 (fig. 1), 3; Beresford 1998, pp. 192–3; Postle 1998, p. 12; Schama 1999, pp. 521, 522 (fig.), 523–6, 719 (note 13); Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 89–128, 159, 167, 169–70, 174, 224–7, 229, 237, 242–3 (Rembrandt’s Maid (Girl at a window)); Mannings & Postle 2000, i, pp. 531 (under no. 2073), 585 (under no. 2230); Shawe-Taylor 2000, pp. 52–3; Preston 2001, pp. 209–13; Williams 2001, pp. 182, 184, 187; Cavalli-Björkman 2003; Cavalli-Björkman in Cristina 2003, p. 252, under no. 123; Korevaar 2005, pp. 39 (fig. 29), 51 (notes 35–7); Van de Wetering 2005, pp. 263 (under IV 7), 392 (under IV 5), 407–8 (fig. 6) (under no. IV 7); Van de Wetering in Rembrandt 2006, p. 307, under nos 33–4; Van de Wetering 2006b, pp. 191, 193 (fig. 220); Van de Wetering 2006c, pp. 174 (fig. 20), 185; Cavalli-Björkman 2005, p. 407 (fig.); Cavalli-Björkman 2006, pp. 194 (fig. 13a), 285, under no. 13; Schwartz 2006, pp. 62–3 (fig. 97), 93; Liedtke 2007, p. 206 (note 11), under no. 46; Blanc 2008, p. 60 (note 21), fig. 22; Hirschfelder 2008, pp. 126 (note 70), 423, no. 439, fig. 93; Solkin & Simpson 2009, pp. 37–8; Dejardin 2009b, pp. 6–7 (still with the gold necklace); Korthals Altes 2009–10, p. 197; Keyes, Rassieur & Weller 2011, pp. 46–7, fig. 18; Van de Wetering 2011, p. 375 (under V 4); Raux 2012, pp. 92–3; Percival 2012, pp. 138–43; Ševčík, Bartilla & Seifertová 2012, p. 505, under no. 504 (Amsterdam School(?), 2nd half of the 17th century); Scott 2013, pp. 580, 599 (fig. 10), 604–5 (note 66); Fritzsche 2013, pp. 247, 249 (fig. 2); Van de Wetering 2015, p. 589, fig. 200; Weststeijn 2015a, i, p. 118, ii, p. 365 (note 165), 481 (fig. 32); De Belie 2015, pp. 59–60, fig. 44; De Witt, Van Sloten & Van der Veen 2015, pp. 76, 78; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 165–8, 172; Van de Wetering 2017, i, p. 313 (fig. 200), ii, p. 589, no. 200; Salomon 2017, pp. 51 (fig. 33), 54; Seifert 2018, p. 39 (fig. 33, colour), 126, no. 7; Schmid 2018, pp. 143–4 (fig. 7.12); Manuth, De Winkel & Van Leeuwen 2019, pp. 359, 708–9, no. 322 (gold necklace); RKD no. 40025: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/40025 (Feb. 13, 2019).

EXHIBITIONS

London 1815, p. 14, no. 14, ‘A girl looking from a window; Rembrandt; Dulwich College’; London 1843, p. 12, no. 107, ‘A Girl Looking from a Window; Rembrandt; Dulwich College’; London 1899, pp. 7, 16, no. 32; London/Leeds 1947–53, n.p., no. 37 (fig. in Leeds version); Edinburgh 1950, p. 12, no. 21 (E. K. Waterhouse); Amsterdam 1952, p. 70, no. 142, fig. 30; London 1952–3, p. 31, no. 122 (fig. in Illustrated Souvenir); London/Washington/Los Angeles 1985–6, pp. 100–102, no. 26 (C. White); Tokyo/Shizuoka/Osaka/Yokohama 1986–7, pp. 114–16, no. 26 (in Japanese; C. White); London 1989;29 Stockholm 1992–3, pp. 194–5 (fig.), no. 56 (G. Cavalli-Björkman); London 1993, p. 55, no. 1 (C. White); Japan 1999, pp. 108–9, 170, no. 30 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 156–7, no. 49 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Edinburgh/London 2001, pp. 188–9, 258, no. 104 (J. Lloyd Williams); Berlin 2006, pp. 328–9, no. 44 (M. de Winkel); London/Paris/Madrid 2009–10, pp. 150–51, no. 43 (D. Solkin & P. Simpson); New York 2010, pp. 34–7, no. 3 (X. F. Salomon); Edinburgh 2018, p. 39 (fig. 33, colour), 126, no. 7 (C. Hoitsma and C. T. Seifert); London 2019–20, pp. 8, 28–9, 31, 64, 65 (colour ill.), 76, 78, 79 (fig. 24), 81, 149 (note 164), 159 (colour ill.), cat. 17.

TECHNICAL NOTES

Plain-weave canvas. The ground is a single red-brown layer: a mixture of quartz and earth pigments. The paint was thickly applied with strong brush texture and much impasto. X-rays [1] revealed changes in the composition: the proper right arm has been moved a little closer to the figure and the stone block at the right was painted over part of the white shirt. There are many pentimenti; two blocks of stone in the lower right-hand corner are painted over a metallic object, possibly a helmet.

Glue-paste lined and strip-lined; the original tacking margins are absent. The painting was probably originally rectangular, indicated by cusping that is present on the straight edge at the top but absent in the curved corners. The paint surface has a raised craquelure all over, especially in a band across the lower part of the painting. There are several restored losses in the figure and background, including a line of losses in the proper left sleeve. Edges of the craquelure overlap in this area due to shrinking of the original canvas, which may have been caused by water damage or during lining. The tonality of the dark areas has evidently changed with time. To the upper right of the figure there is an area where brushstrokes form a regular diamond pattern with neat vertical brushstrokes below. This might be a hanging textile with a fringed lower edge. Paint sample analysis identified large particles of azurite and some red lake, mixed with bright red earth and black. This suggests that this enigmatic area was once a deep purple.

Previous recorded treatment: 1866, ‘revived’, varnished and relined onto a new stretcher by Holder; 1938, cleaned, Dr Hell; 1947, cleaned/restored (green curtain removed by Dr Hell); 1950s, reframed; 1980, examined, National Maritime Museum; 1992, technical analysis, Courtauld Institute of Art, Dr A. Burnstock; 2000, frame treated for insect infestation; 2005, consolidated, cleaned and restored, revarnished, S. Plender.

RELATED WORKS

1a) (paired with DPG163 between 1732 and 1776) Govert Flinck, A Young Woman as a Shepherdess (Saskia as Flora), falsely signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1633, canvas, 66.7 x 50.5 cm (oval). MMA, New York, Bequest of Lilian S. Timken, 1959, 60.71.15 [2].30

1b) Preparatory drawing: Rembrandt, Study for the painting ‘A Girl at a Window’ of 1645, black chalk touched with white, 83 x 65 mm. Courtauld Gallery, Princes Gate Bequest, London, D.1978.PG192 [3].31

1c.I) Pieter Lastman, The Wedding Night of Tobias and Sarah (Tobias 8:23), signed and dated P. Lastman fecit 1611, panel, 41.2 x 57.8 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 62.985.32

1c.II) Rembrandt, A Woman in Bed / Sarah waiting for Tobias, c. 1647, signed and dated Rembra[…] f. 164[7], canvas, 81.1. x 67.8 cm (arched top). National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, NG 827 [4] .33

1d) Rembrandt, The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch (The Nightwatch), signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1642, canvas, 379.5 × 453.5 cm. RM, Amsterdam (on loan from the City of Amsterdam), SK–C–5.34

Pictures of similar girls by Rembrandt and his school

2a) Jan Victors, Young Girl at a Window, signed and dated JAN FICTOOR.FE 1640, canvas, 93 x 78 cm. Louvre, Paris, 1286 [5].35

2b.I) (pair with 2b.II?) Rembrandt, Girl in a Picture Frame, signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1641, panel, 105.5 x 76.3 cm. Royal Castle, Warsaw, ZKW/3906.36

2b.II) (pair with 2b.I?) Rembrandt, Scholar at his Writing Table, signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1641, panel 105.7 x 76.4 cm. Royal Castle, Warsaw, ZKW/3905.37

2c) Rembrandt, A Girl at a Window (The Kitchen Maid), signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1651, canvas, 78 x 63 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NM 584 [6].38

2d) Studio of Rembrandt, Girl with a Broom, c. 1646–7, falsely signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1651, canvas, 107.3 x 91.4 cm. NGA, Washington, 1937.1.74.39

2e) Attributed to Samuel van Hoogstraten, Girl in a Half-Door, canvas, 75 x 60 cm (arched top). Marquess of Tavistock and the Trustees of the Woburn Estates, Woburn Abbey, 1405.40

2f) Attributed to Samuel van Hoogstraten, Girl at an Open Half-Door, c. 1645, falsely signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1645, canvas, 102.5 x 85.1 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Mr & Mrs Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1894.1022.41

Headdress

3a) Rembrandt, The Death of the Virgin, signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1639, etching and drypoint, 410 x 315 mm. BM, London, F,5.26.42

3b) Rembrandt, Three Studies of a Child, One Study of a Woman, c. 1640–45, brown ink, brown wash, and white opaque watercolour on white antique laid paper, 215 x 161 mm. Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Gift of Meta and Paul J. Sachs, 1949.4 [7].43

3c) Stefano della Bella, Two studies of a woman with a North Holland headdress, c. 1647, pen in brown ink over black chalk, 95 x 110 mm. Private collection.44

Some later copies and variations

France

4a.I) Copy (with a basket of onions): Jean-Baptiste Santerre, La Jardinière, c. 1708–9, canvas, 81 x 65 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Orléans, 14 [8].45

4a.II) Studio of Jean-Baptiste Santerre, L’Attention, canvas, 72 x 52 cm. Musée national du château de Fontainebleau, 8698 4.46

4b) Print after no. 4a.I (in reverse): Pierre Louis (de) Surugue after Jean-Baptiste Santerre, Sylvie at a Window, c. 1719, inscriptions, etching and engraving, 258 x 189 mm. BM, London, 1874,0808.1825.47

4c) Pastiche: Jean Raoux, A Girl at a Window, drawing, 210 x 165 mm. Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon, D.1583.48

4d) Copy (flowers added): French, first half of the 19th century (formerly attributed to Jean Raoux), 86.5 x 90.7 cm. Museé des Beaux-Arts, Libourne, D.2004.1.69.49

Germany

5a) Free copy: Antoine Pesne (1683–1757), Girl at a Window. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, Potsdam-Sanssouci.50

5b) Print (same direction): Carl Gottlieb Rasp, engraving, signed and dated Rinbrant inv. C.GF. rasp sc. 1770/6 (?).

Great Britain

6a) Copy: A. Grenville-Scott, Girl at a Window, 1774 or 1779, pastel, 654 x 546 mm. Lord Polworth collection.51

6b) Copy: formerly attrib. to Sir Joshua Reynolds, Girl at a Window, canvas, 62.9 x 53 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg.52

6c) (inspiration) Sir Joshua Reynolds, The Laughing Girl, canvas, 91.5 x 71.2 cm. The Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood (English Heritage).53

6d) (inspiration) John Opie, Mrs Opie, c. 1806, canvas, 89.3 x 63.7 cm. Private collection, UK.54

6e) Print (same direction): William Say, Rembrandt’s Peasant Girl, c. 1814, mezzotint, hand-coloured, 505 x 349 mm. BM, London, 1861,1109.286 [9].55

6f) (inspiration) J. M. W. Turner, Jessica, exh. 1830, canvas, 122 x 91.5 cm. Tate Britain (at Petworth House), T03887.56

6g) Print (same direction): John Rogers, inscriptions, 1830s, mezzotint, 168 (trimmed?) x 128 (trimmed?) mm. BM, London, 2010,7081.6963.57

6h) Miniature copy: Isabella Fawcett, c. 1840, watercolour, 138 x 113 mm. Private collection, UK.58

6i) Copy: Unknown artist, c. 1870s, canvas, 63.5 x 50.8 cm (oval). Private collection, UK.59

6j) Frances L. Grace, The Dulwich Rembrandt, c. 1878–9, canvas, 26.3 x 28.8 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Morgan Grenfell & Co. Ltd, 1993) [10].60

6k) Copy: Tom Keating, c. 1950s, watercolour and pencil underdrawing, 360 x 290 mm. Private collection, UK.61

6l) Free copy: Simon Edmondson, inscribed and dated Study at Dulwich 17.9.90, canvas, 22.5 x 33 cm. Grob Gallery, London.62

6m) Copy: Unknown artist, Paraja, the Mulatta Slave of Valasquez, lithograph, photo Warburg Institute.63

United States

7a) Copy after DPG163 and no. 6e: Thomas Sully, Rembrandt’s Peasant Girl, copper, 15.8 x 21.6 cm. Private collection, San Francisco, 1851.64

7b) Free copy: Rembrandt Peale, Portrait of Rosalba Peale, 1846. El Paso Museum of Art, Fort Worth, Texas.65

Comparable trompe l’œil

8a) Flemish School, Boy at a Window, c. 1550–60, panel, 73.8 x 61.6 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 404972.66

Gold chain

9) Rembrandt, Self-Portrait in a Flat Cap, 1642, panel, 70.4 x 58.8 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN, 404120.67

Lent to the RA to be copied in 1816, 1839, 1855, 1861, 1867, 1878, 1879, 1880, 1890, and 1899(?).

DPG163

Rembrandt

Girl at a window, dated 1645

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG163

1

X-ray of DPG163

2

attributed to Govert Flinck

A young woman as a shepherdess, second half of the 1630s

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 60.71.15

3

Rembrandt

Girl at a window, c. 1645

London (England), Courtauld Institute of Art, inv./cat.nr. D.1978.PG.192

4

Rembrandt

A Woman in bed, dated 164[7]

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), National Galleries Scotland, inv./cat.nr. NG 827

5

Jan Victors

Young girl at the window, 1640 (dated)

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 1286

6

Rembrandt

Young girl at a window, dated 1651

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. NM 584

7

Rembrandt

Three studies of a child, one of a woman, c. 1638-40

Cambridge (Massachusetts), Fogg Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1949.4

8

Jean-Baptiste Santerre after Rembrandt

Girl at a window, c. 1717

Orléans (Loiret), Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, inv./cat.nr. 14

9

William Say after Rembrandt

Rembrandt's Peasant Girl, ca. 18143-1814

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1861,1109.286

10

Frances L. Grace

Students copying Rembrandt's Girl at a Window at the Royal Academy, c. 1878-1879

London (England), Morgan Grenfell & Co. Ltd

2

attributed to Govert Flinck

A young woman as a shepherdess, second half of the 1630s

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 60.71.15

DPG163

Rembrandt

Girl at a window, dated 1645

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG163

With the exception of Waagen, who in 1854 amazingly thought there was no genuine Rembrandt in the Dulwich collection, no one has doubted the attribution, or the signature and date. Like DPG99, this is used as a standard against which to judge unsigned and undated pictures, in this case of the mid-1640s.

The painting probably did not originally have a curved top: there is cusping in the straight part of the top edge, but not in the curved corners.68 The early 18th-century copy by Jean-Baptiste Santerre (1651–1717) is rectangular (Related works, no. 4a) [8], with an arch painted in the composition, which might show the situation about 1709, when it seems that DPG163 was still in the collection of Roger de Piles, the famous French theoretician (see below). The copy formerly attributed to Sir Joshua Reynolds (Related works, no. 6b) has a straight top, but that need not reflect the original. The picture had a curved top when it was sold in Paris in 1776, and that was probably already the case in 1747 when Gersaint noted it as forming a pair with Govert Flinck’s Flora (Related works, no. 1a) [2], which had been enlarged to match.69 There are other Rembrandt pictures with an arched top, such as the Woman in Bed / Sarah waiting for Tobias in Edinburgh (Related works, no. 1c.II) [4] with almost the same dimensions as DPG163, but dated somewhat earlier. Although that picture has no tacking edges, it seems always to have been arched at the top.70 Van de Wetering makes a rather convincing case for this picture having been ‘a trompe l’oeil box-bed scene on a door of an actual box-bed’.71 Could that also have been the case with DPG163?

The provenance is based on one worked out by Michiel Roscam Abbing.72 The earliest mention of what must be the DPG picture is in Roger de Piles’ Cours de peinture par principes of 1708,73 where he discusses a portrait by Rembrandt of his female servant that he himself had bought in Amsterdam. When that picture was sold from the collection of the Vicomte de Fonspertuis it was described as a jeune fille […] qui a les deux coudes appuyés sur une Table – a girl resting both elbows on a table. There has been confusion with several other paintings by Rembrandt, or once attributed to him, in which similar girls are depicted in half-length – one at Woburn Abbey (Related works, no. 2e), one in Stockholm (Related works, no. 2c) [6], and one in Chicago (Related works, no. 2f). However, as only in DPG163 does the girl rest both elbows on a support – albeit not a table, but a stone ledge – it is likely that it is what was in the collection of Roger de Piles and after that in several other French collections listed by Gersaint.

De Piles goes on to say that Rembrandt put the picture in one of the windows in his house, and for a few days people thought that the servant really was there. He states that this was not due to beautiful drawing (dessein) or to nobility of expression (noblesse des expressions). When de Piles was in Holland he went to look at the painting. He was impressed by the beautiful brushwork (un beau pinceau) and strength of character (une grande force), and he decided to buy it for his collection. Roscam Abbing says that de Piles interpreted the picture as one of Rembrandt’s trompe-l’œil experiments and that he purchased it, and took it to Paris when he was banished from the Netherlands in 1697. He goes on to prove, however, that DPG163 could not have been displayed in a window of Rembrandt’s house [11] because it is too small, and the lighting and stone ledge would not work in that setting.74

Hofstede de Groot and other authors did not include de Piles’ anecdote.75 In general the story was considered to be a 17th-century variant on the ancient story of the competition between Zeuxis and Parrhasios (so a topos and not necessarily true), two Greek painters who tried to deceive each other by painting very illusionistic objects:76 a clever artist could paint realistic objects and animals, but only a very clever artist could paint people so realistically that he could deceive the viewer and even another painter. That is what Rembrandt did, and what de Piles appreciated in his work.

DPG163 is a type of picture that was popular in the 16th (Related works, no. 8a) and 17th centuries, in which the sitter seems to reach out into the realm of the viewer – by leaning out of a window, reaching out a hand, leaning on a picture frame (Related works, no. 2b.I), drawing aside a curtain (Related works, no. 1cII) [4], or stepping forward (Related works, no. 1d). Rembrandt and his pupils were particularly intrigued by the possibilities of trompe l’œil from the early 1640s to the mid-1650s. The earliest dated picture depicting a girl leaning out of a window seems to be by Jan Victors (1619–76/7), perhaps a pupil of Rembrandt, of 1640 (Related works, no. 2a) [5].

Valentiner suggested that Rembrandt used Hendrickje Stoffels as a model.77 This was rejected on the grounds that she would have been too old: in 1645 Hendrickje was nineteen, and the girl looks much younger; moreover, Hendrickje is only documented in the Rembrandt household from October 1649. Wheelock stated that the Girl with a Broom in Washington, now attributed to Samuel van Hoogstraten (Related works, no. 2d), has an ‘extremely close physical resemblance’,78 and the same can be said of the Stockholm Kitchen Maid (Related works, no. 2c) [6]. All these pictures are on the borderline between portrait and genre,79 at least for later eyes, starting with de Piles who saw a portrait of a servant in it. This ambiguity is probably what makes them so attractive. There is another ambiguity, too: in 1824 Patmore concluded that it was not possible to determine the sex of the sitter; in an 18th-century Swedish inventory the Kitchen Maid was recorded as a ‘young boy’.80 The setting, with the stone ledge and the dark background, is indistinct. Rembrandt seems to have offered a visual mystery to arouse curiosity: the picture seems very realistic, but what do we really see? The only surviving related study (Related works, 1b) [3] is no help: the girl rests her arms straightforwardly on a table, and there is something negroid about her eyes and nose.81

Several attempts have been made to interpret the subject.82 Koslow in 1975 argued that it illustrates idleness: the girl hides her right hand ‘in her bosom’ (in fact in her sleeve), so she is an example of the idle servant, an iconographic theme that goes back to the 15th century.83 Wheelock in 1993 rejected that interpretation; and indeed, albeit in France a century later, a copy of the picture was given the title L’Attention, the opposite of idleness (Related works, no. 4a.II).

Another suggestion was that, because of what was read as a gold chain around her neck, she was a courtesan. But her arms that are half sunburnt, and even seem to have some insect bites, indicate that she is a girl who lives and works in the open air. William Say called his mezzotint of 1814 Rembrandt’s Peasant Girl (Related works, no. 6e) [9]. The gold chain is a problem for the interpretation of the girl as a simple servant, as she had been called since Roger de Piles in 1708. A solution was offered by inventories of such girls, where the only valuable possession was often a gold chain; and Rembrandt could have lent her one as a prop. However, very careful examination shows that what is around her neck is not two rows of the same gold chain but two ties of her loose gown, with the same decoration as on the cuffs and on the seam between the bodice and the sleeves. Our recent observation was already noticed and published by Ann Sumner in 1994, but her entry was clearly not noticed by later writers.84 At the 2019–20 exhibition at Dulwich, where DPG163 hung near Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait from the Royal Collection (Related works, no. 9), painted three years earlier, it became very clear how Rembrandt painted a real gold chain.

The possibility that the girl might be the protagonist of an Old Testament story was investigated and dismissed.85 However the Woman in Bed in Edinburgh, as she is called by the gallery there (Related works, no. 1c.II) [4],86 was rather convincingly interpreted as Sarah waiting for Tobias on their wedding night by Van de Wetering in 2015 (following Tümpel), from the example of that scene by Pieter Lastman dated 1611 (Related works, no. 1c.I). Her (Jewish?) metal headdress seems to be Rembrandt’s invention,87 as does the cap with a red tassel in DPG163.88 A little girl in a drawing apparently from life (Related works, no. 3b) [7] appears to wear a ribbon intricately encircling her head, with hanging ends, somewhat similar to that in DPG163. Headdresses were a feature of costume in North Holland: a print of the Death of the Virgin, c. 1639, shows one on a young woman at the far right (Related works, no. 3a), and the Italian draughtsman Stefano della Bella recorded one during his travels in the Netherlands (Related works, no. 3c); but in neither case are there ribbons or tassels as in DPG163. Marieke de Winkel thinks it highly unlikely that a servant girl would have been dressed in a shirt only, and considers that the shirt and the cap are a kind of fantasy clothing, which gives her, and other girls and women similarly depicted by Rembrandt, a strong romantic and timeless note.89

Thus what Rembrandt painted here, as part of the exercises in trompe-l’œil effects that interested him at the time, is a very realistic, illusionistic, and attractive picture of a girl, which has so far defied interpretation. That is probably exactly what he wanted: a picture that still after nearly four hundred years invites the viewer to look very carefully, and to engage in finding new meanings.

The picture led to many copies and variations in France, Germany, Great Britain and the United States, of which the list of Related works gives only a selection (nos 4a–4d, 5a–5b, 6a–6m [8-10], 7a–7b). The pupils of the Royal Academy had to copy it nine or ten times in the 19th century. In 1949 it was at £33,000 the most expensive of the sixteen Dulwich paintings which were then valued by Thomas Agnew and Sons (the cheapest, at £100, was Adriaen van de Velde’s DPG51 Cows and Sheep in a Wood). DPG163 is still considered to be one of the highlights of the Dulwich Picture Gallery collection, if not the image of the collection.

8

Jean-Baptiste Santerre after Rembrandt

Girl at a window, c. 1717

Orléans (Loiret), Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, inv./cat.nr. 14

4

Rembrandt

A Woman in bed, dated 164[7]

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), National Galleries Scotland, inv./cat.nr. NG 827

6

Rembrandt

Young girl at a window, dated 1651

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. NM 584

11

DPG163 photoshopped behind a window of Rembrandt’s house

3

Rembrandt

Girl at a window, c. 1645

London (England), Courtauld Institute of Art, inv./cat.nr. D.1978.PG.192

5

Jan Victors

Young girl at the window, 1640 (dated)

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 1286

9

William Say after Rembrandt

Rembrandt's Peasant Girl, ca. 18143-1814

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1861,1109.286

7

Notes

1 Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 96–9, 225 (note 3). De Piles was in the Netherlands on behalf of the French king Louis XIV (1638–1715). He was arrested as a spy in Amsterdam in 1693, imprisoned in Loevestein Castle until 1697, and then banished. While he was in prison de Piles seems to have worked on his Abregé de la vie des peintres that was published in 1699 (a second edn appeared in 1715).

2 Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 100 (note 39), 225 (note 3).

3 This owner is mentioned as the uncle of Fonspertuis in his sale catalogue (Lugt 682): see note 7 below. See also Roscam Abbing (1999, pp. 167, 170 (note 81), 224), who refers for Duvivier to Wildenstein 1924, p. 6.

4 Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 167–8, 227, based on Rambaud 1964–71, i, (1964), p. 571. Cailleux 1975, p. 302 (note 18), had already suggested that DPG163 was in the collection of M. de Morville. Roscam Abbing proposed the combination with Govert Flinck’s Flora (Related works, no. 1): Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 168–70 (fig. 45).

5 Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 167 (note 62), based on Pichon 1880, ii, p. 80. On the collection of this Polish count, who lived in Paris, see Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 151–74.

6 Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 167 (note 63), based on Pichon 1880, ii, p. 86.

7 GPID (7 Dec. 2013), no. 435, and Gersaint 1747, pp. 198–202: Un autre Portrait de même forme & de même grandeur que le précédent, peint par le même Rimbrant. Ce morceau est de la plus haute réputation parmi les Amateurs. Il est regardé comme un des Chef-d’œuvres [sic] de ce grand Maître, & en effet, il le mérite. C’est le portrait de sa Servante, peinte par lui-même. Voici ce que rapporte M. de Piles, dans son Abrégé de la Vie des Peintres, au sujet de ce Tableau qu’il possedoit. Le trait est singulier, & quoique plusieurs en soient instruits, ceux qui n’en ont point de connoissances, ne seront peut-être pas fachés de le trouver ici. “Rimbrant, (dit M. de Piles, à la page 423 de l’Edition de 1715) sçavoit fort bien, qu’en Peinture, on pouvoit sans beaucoup de peine, tromper la vûe, en représentant des Corps immobiles & inanimés; & non content de cet artifice assez commun, il chercha avec une extrême application, celui d’imposer aux yeux, par des Figures vivantes. Il en fit entr’autres une épreuve par le portrait de sa Servante qu’il exposa à sa fenêtre, dont toute l’ouverture étoit occupée par la toile du Tableau. Tous ceux qui le virent y furent trompés jusqu’à ce que le Tableau ayant été exposé durant plusieurs jours, & l’attitude de sa Servante, étant toujours la même, chacun vint enfin à s’appercevoir qu’il étoit trompé. Je conserve aujourd’hui cet Ouvrage dans mon Cabinet.” Il est vrai que rien, en peinture, ne peut être plus frappant que ce Portrait, & la nature n’est pas plus vraye. Rimbrant y a employé cette magie de la couleur, dont il a été le Maître, supérieurement à tout autre. Il représente une jeune fille, espece de Cuisinière, d’une phisionomie assez picquante, qui a les deux coudes appuyés sur une Table. On l’appelle, entre les Curieux, La Crasseuse de Rimbrant. La lumière est frappée avec tant d’art, & tant d’intelligence sur la Figure qui se détache sur un fond brun, & les différens degrés en sont si bien ménagés, qu’elle paroît être tout à fait en dehors de la Toile. Les couleurs quoi qu’opposées dans leur nature, & dans leurs effets, ont entre elles un accord si parfait, qu’on n’en peut distinguer les passages, ni les différences. Le pinceau y est gras & moëlleux, tel qu’on le voit ordinairement dans les beaux ouvrages de ce Maistre. Enfin ce morceau en général, est si sçavant, & si piquant, qu’il est douteux que l’on puisse jamais lui trouver un véritable pendant. Ce Tableau, depuis la mort de M. de Piles, a passé successivement dans les Cabinets des plus fameux, où rien n’entroit qui ne fût décidé assez parfait, pour mériter d’y trouver place. Il y a tout lieu de penser qu’il aura encore aujourd’hui le même avantage. C’est M. Duvivier, Officier dans les Gardes Françoises, & Oncle de M. de Fonspertuis, qui l’a possedé après M. de Piles. De-là il passa à M. le Comte d’Hoym, après le décès duquel M. de Morvile en fit l’acquisition; & enfin M. de Fonspertuis s’en rendit l’Acquéreur à la vente que l’on fit après la mort de ce Ministre (pendant du lot 434). (Another portrait of the same shape and size as the previous one, painted by the same Rimbrant. This piece is of the highest reputation among art-lovers. It is regarded as one of the masterpieces of this great master, and indeed deservedly so. It is the portrait of his servant, painted by himself. Here is what M. de Piles says, in his Abrégé de la Vie des Peintres, about this picture that he owned. The style is distinctive, and although many know it, those who do not may not be sorry to find it here. “Rimbrant, (says M. de Piles, on page 423 of the 1715 edition) was well aware that in painting one may, without too much difficulty, deceive the eye in depicting immobile and inanimate objects; and not content with this fairly common artifice, he strove after the means whereby to trick the eyes with living bodies. He tested this on others with the portrait of his serving-girl which he placed in his window, so that the whole aperture was filled with the canvas. All those who saw it were deceived, until the painting having been there for several days, and the posture of his serving-girl remaining always the same, everyone began to realise that they had been tricked. I now have that painting in my cabinet.” [De Piles transl. Roscam Abbing 1993a, pp. 19, 24 (note 3)] Indeed nothing in painting can be more striking than this portrait, and nature is not more realistic. In it Rimbrant used that magic of colour of which he was the master above all others. It depicts a girl, a sort of cook, with a rather titillating appearance, who has both elbows resting on a table. It is known among connaisseurs as Rimbrant’s The Slattern [La Crasseuse]. The light strikes with so much art and so much intelligence on the figure that stands out against a brown background, and its different shadings are so well managed, that it seems to be completely outside the canvas. The colours, no matter how opposite in their nature and in their effects, harmonize so perfectly that it is impossible to distinguish between the passages or the differences between them. The brush is broad and soft, as is usual in the beautiful works of this master. Finally, this piece as a whole is so skilful and so enticing that it is doubtful whether one could ever find a true pendant to it. Since the death of M. de Piles, this Picture has passed in succession through the most celebrated cabinets, where nothing entered that was not perfect enough to deserve a place there. There is every reason to believe that it will have the same advantage today. M. Duvivier, Officer in the French Guards and uncle of M. de Fonspertuis, owned it after M. de Piles. From there it passed to M. le Comte d’Hoym, after whose death it was acquired by M. de Morvile; & finally M. de Fonspertuis acquired it at the sale that was held after the death of that minister (pendant of lot 434).) See also Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 229.

8 GPID (7 Dec. 2013), no. 434, also Gersaint 1747, pp. 197–9: Un Joli Portrait de femme couronnée de fleurs, & peint sur bois par Rimbrant. Il a trente pouces de hauteur, sur vingt-trois pouces trois quarts de largeur. Ce Morceau est connu parmi les Curieux, sous le nom de la belle Jardiniere. On sçait que ce Maître n’a guéres fait de Portraits de femme, ce qui les fait beaucoup rechercher; sur-tout quand ils sont d’une phisionomie aimable & jeune. Celui-ci est de ce genre; sa forme est ceintrée par le haut. Il peut servir de pendant au suivant, ayant même été agrandi à cet effet. (Pendant du lot 435). (A pretty portrait of a woman crowned with flowers, and painted on wood by Rimbrant. It is thirty inches high and twenty-three and three quarters inches wide. This piece is known among the connoisseurs as the beautiful Gardener. It is known that this master made hardly any portraits of women, which makes them very desirable, especially when they have a pleasant and youthful appearance. This one is of that type; the painting is curved at the top. It can serve as a pendant for the next one, having indeed been enlarged for that purpose. (Pendant of lot 435)). See also Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 229.

9 GPID (7 Dec. 2013), no. 70 and Rémy 1776, p. 25, no. 70: La servante de Rembrandt, connue sous le nom de la Crasseuse; elle est peinte sur une toile ceintrée par le haut, qui porte 30 pouces de hauteur, sur 23 pouces 9 lignes de largeur. Les suffrages unanimement accordés à ce morceau, suffisent pour nous dispenser d’en faire un long éloge. Il a appartenu à M. de Pilles [sic] qui en a fait mention dans sa Vie des Peintres, à la page 423 de l’édition de 1715. M. de Fonspertuis en a été aussi possesseur; voyez le Catalogue fait, après son décès, par Gersaint, no. 435. (Rembrandt’s serving-maid, known as the Slattern; she is painted on a canvas curved at the top, 30 inches high, 23 inches and 9 lines wide [French]. The unanimous praise granted to this work makes it unnecessary to give a long eulogy of it. It belonged to M. de Pilles [sic] who mentioned it in his Lives of the Painters, on page 423 of the 1715 edition. It was also owned by Mr. de Fonspertuis; see the Catalogue made after his death by Gersaint, no. 435.) See also Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 237. The pair was broken up, as the pendant (Flinck’s Flora), no. 71, was sold to Alexandre-Louis Hersant Destouches, and ended up in New York (Related works, no. 1). NB: according to GPID (19 May 2015) lot 70 is now in Stockholm (Related works, no. 2c).

10 Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 237.

11 GPID (Dec. 9, 2013); according to Murray 1980a, p. 101, it measured 33 x 29 inches (= 2'9" x 2'5"), which could be right. However, whether the girl in DPG163 can be called a ‘woman’ is questionable.

12 Rembrant, par exemple, se divertit un jour à faire le portrait de sa servante, pour l’exposer à une fenêtre & tromper les yeux des passans. Cela lui réüssit ; car on ne s’apperçût que quelques jours après de la tromperie. Ce n’étoit, comme on peut bien se l’imaginer de Rembrant, ni la beauté du dessein, ni la noblesse des expressions, qui avoient produit cet effet. Etant en Hollande j’eus la curiosité de voir ce portrait que je trouvai d’un beau pinceau & d’une grande force, je l’achetai, & il tient aujourd’hui une place considerable dans mon cabinet. (Rembrandt, for instance, amused himself one day by painting the portrait of his servant girl, to place it in a window and trick passers-by. It worked, for the deception was only discovered several days later. As one can imagine with Rembrandt, it was neither the beautiful design nor the nobility of expression that had that effect. When I was in Holland I wanted to see this portrait. I was struck by the beautiful brushwork and great power; I bought it, and to this day it has an important place in my cabinet.) Transl. in Van de Wetering 2015, p. 589, and Salomon 2010, p. 36, and amended by Emily Lane.

13 Il [Rembrandt] savoit fort bien qu’en Peinture on pouvoit, sans beaucoup de peine, tromper la vûe en representant des corps immobiles et inanimés; et non content de cet artifice assez commun, il chercha avec une extrême application celui d’imposer aux jeux par des figures vivantes. Il en fit entr’autres une épreuve par le portrait de sa servante qu’il exposa à sa fenêtre, dont toute la ouverture étoit occupée par la toile du Tableau. Tous ceux qui le virent y furent trompez, jusqu’à ce que le Tableau ayant éte exposé durant plusieurs jours, et l’attitude de sa servante étant toûjours la même, chacun vint enfin à s’appercevoir qu’il était trompé. Je conserve aujourd’huy cet ouvrage dans mon cabinet. (Rembrandt was well aware that in painting one may, without too much difficulty, deceive the eye in representing immobile and inanimate objects; and not content with this fairly common artifice, he strove after the means whereby to trick the eyes with living bodies. He tested this on others with the portrait of his serving-girl which he placed in his window, so that the whole aperture was filled with the canvas. All those who saw it were deceived, until the painting having been there for several days, and the posture of his serving-girl remaining always the same, everyone began to realise that they had been tricked. I now have that painting in my cabinet.) Transl. Roscam Abbing 1993a, pp. 19, 24 (note 3).

14 Chez M. Blondel de Gagny, on voit [de Rembrandt] une femme couronnée de fleurs, une autre femme appellée la Crasseuse.

15 ‘Rembrandt Van Rhyn. A Girl looking from a Window. In a most charming, open style of day-light, and is one of those chosen by the Royal Academy for the use of their students in 1816.’

16 ‘The first picture calling for particular attention in the centre or third room is 176, A Girl at a Window, by the same artist [Rembrandt]. This is as purely natural and forcible a head as Rembrandt ever painted. It must have been a study from nature; for there is an absolute truth about it that no memory or invention could have given. It is taken from the lowest class of life; and there is a very particular character about it, which is sometimes observable in that class at an early age; namely that, judging from the face merely, you can scarcely determine whether it belongs to a male or female. The character of expression depicted in the human face is so entirely owing to the habits of thought and feeling arising from the circumstances in which we are placed, that, in the very lowest classes of life, and at an early age, before the sexual qualities become developed, you frequently see faces that exhibit no mark of sex whatsoever; and others (as in the instance before us) in which females, from associating indiscriminately with males, and partaking in the same sports and pursuits, acquire the same expression of countenance. The picture before us might just as well have been called “Boy at a Window,” as “Girl.”’

17 About the same as Patmore 1824a (see note 16).

18 ‘The Centre Room commences with a Girl at a Window, by Rembrandt. The picture is known by the print of it [probably Say 1814, Related works, no. 6e], and is one of the most remarkable and pleasing in the Collection. For clearness, for breadth, for a lively, ruddy look of healthy nature, it cannot be surpassed. The execution of the drapery is masterly. There is a story told of its being his servant-maid looking out of a window, but it is evidently the portrait of a mere child.’

19 ‘Rembrandt. A Girl, evidently in the act of closing the shutters, giving one last look out: said to be a portrait of Rembrandt’s maid servant, and so striking in effect, that on being placed at a window, the passers by were deceived by it.’

20 ‘A Peasant Girl, of a comely, good-humoured countenance, and dark curling hair, clad in a loose whitish dress, represented leaning both arms on a sill or wall, with one hand raised to her neck, and her face presented in a front view to the spectator. Engraved by Surugue, and in mezzotinto by Saye. Formerly in the possession of Noel Desenfans, Esq. […] Now in the Dulwich Gallery.’

21 ‘Rembrandt. 206 A Girl leaning out of a Window. Half-length; life-size. A picture wonderful for mingled power and simplicity. It is absolute truth. There is, I think, a mezzotint engraving [Say 1814].’

22 ‘Among the pictures which bear the name of Rembrandt, there are some very good works of his school, but probably none of his own hand’ (originally in Waagen 1838, ii, p. 380).

23 La Servante de Rembrandt, la Crasseuse. Toile cintrée de trente pouces sur vingt-quatre. Ce morceau célèbre a appartenu à M. de Piles, qui en a fait mention dans sa Vie des Peintres, et à M. de Fonspertuis, 6,000liv. (The maid of Rembrandt, the Slattern. Curved canvas, thirty inches by twenty-four. This famous piece belonged to M. de Piles, who mentioned it in his Vie des Peintres, and to M. de Fonspertuis, 6,000 pounds [French]).

24 ‘(A Girl at a Window [added above: Portrait of Rembrandt’s Servant-maid] Rembrandt). Said to have come from Lord Cawdor’s Collection. Smith 178 […] Engraved by Surungue, and in mezzotint by Sage. [left page : ‘The story is given as follows “Rembrandt avait une servante extrêmement babillard: après avoire peint son portrait, il l’exposa à une fenêtre ou elle faisait souvent de longues conversations. Les voisins prirent le tableau pour la servante meme, et vinrent aussitôt sans le dessein de discourir avec elle; mais étonnés de lui parler pendant plusieurs heures, sans qu’elle répondit un seul mot, ils trouvèrent ce silence fort singulier et s’aperçurent enfin de leur erreur” (Rembrandt had a very talkative serving-maid: after he had painted her portrait he displayed it in a window where she often had long conversations. The neighbours took the picture for the maid, and at once came up intending to talk with her; but surprised to have talked to her for several hours without her saying a single word, they found the silence very strange, and finally realized their mistake). Cf: Houssaye. ii 163. cf: Abrégé. Vol: iii. p: 114. De Piles. P: 425.’

25 Rembrandt aussi n’a-t-il pas peint [note 1: On trouve aussi ce motif dans plusieurs de ses eaux-fortes.] plusieurs fois ce sujet d’une femme à la fenêtre, par exemple la Crasseuse (Smith, 506), de la collection Blondel de Gagny; La Lady qui écarte un rideau (Smith, 549); la jeune fille, de Dulwich Gallery [note 2: Il est singulier que M. Waagen, qui connaît et qui aime Rembrandt, n’accepte pas comme un tableau original cette belle fille de Dulwich Gallery: ‘Parmi les peintures qui portent le nom de Rembrandt (à cette galerie de Dulwich) se trouvent quelques bons ouvrages de son école, mais aucun qui puisse être de lui.’ (Kunstwerke, etc., t. II, p. 488) – À la verité, les autres tableaux attribués à Rembrandt dans la collection très-précieuse, mais un peu mêlée, de Dulwich College, ne sont pas du maître, mais la Girl at a window, no. 206 du catalogue, est parfaitement originale, et même superbe. M. Passavant l’admire beaucoup, et, contrairement à M. Waagen, il la vante, dans son Kunstreise in England, comme une ‘peinture vivante et parlante, d’une grande exécution et d’un grand charme de couleur.’ Seulement, il se trompe en prenant cette fillette pour la célèbre Crasseuse, aujourd’hui perdue, et qui n’était qu’une ‘vieille et très-ordinaire personne,’ selon les termes de Smith.] (Smith, 532), datée 1645 et gravée par Geyzer; – le plus beau de tous ses portraits de femme en buste, la Lady à l’éventail, de Buckingham Palace, encadrée dans le cintre d’une fenêtre et cotant sa petite main gauche au pilastre latéral. Tout le monde connaît l’histoire – ou la fable – du tableau baptisé la Crasseuse, représentant la servante de Rembrandt en train de fermer le volet d’une fenêtre ; cette peinture ayant été placée sans doute à la façade de la maison sur la rue fit illusion aux passants, qui prirent pour une personne naturelle la figure peinte. – Ainsi parle la chronique. Ce motif d’une femme paraissant à la fenêtre qu’elle va fermer semble avoit été indiqué souvent par Rembrandt à ses élèves, qui devaient avoir connaissance des tableaux analogues peints par leur maître et qui les imitaient de souvenir, plus ou moins, en travaillant d’après nature, dans leurs petits ateliers séparés, en haut de la Breestraat. (Rembrandt also painted [note 1. This motif is also seen in some of his etchings.] several times this subject of a woman at a window, for example the Crasseuse (Smith, 506), in the Blondel de Gagny collection; the Lady parting a curtain (Smith, 549); the girl in Dulwich Gallery [note 2. It is odd that Mr Waagen, who knows and loves Rembrandt, does not accept this beautiful Dulwich Gallery girl as an original picture: ‘Among the paintings that bear the name of Rembrandt (in this Dulwich gallery) there are some good works of Rembrandt’s school, but none that could be by him.’ (Kunstwerke, etc., vol. II, p. 488) – In reality, the other paintings attributed to Rembrandt in the very valuable but somewhat uneven collection of Dulwich College are not by the master, but the Girl at a window, no. 206 in the catalogue, is entirely original, and indeed superb. Mr Passavant admires it very much, and, unlike Mr Waagen, he praises it, in his Kunstreise in England, as a ‘living and speaking painting, of great execution and great charm of colour .’ However, he is mistaken in thinking that this girl is the now-lost famous Crasseuse, who was only an ‘old and very ordinary person’, in Smith’s words.] (Smith, 532), dated 1645 and engraved by Geyzer; – the most beautiful of all his bust-length portraits of a woman, the Lady with a fan, in Buckingham Palace, framed in a window and holding the upright with her small left hand. Everyone knows the story – or the fable – of the painting called la Crasseuse, depicting Rembrandt’s maid closing the shutter of a window; this painting having been placed, no doubt, on the street front of the house misled passers-by, who took the painted figure for a real person. – According to the chronicle. This subject of a woman appearing at a window that she is about to close seems to have been frequently suggested by Rembrandt to his pupils, who must have known similar paintings by their master and imitated them from memory, more or less, working from life in their little separate workshops at the top of Breestraat.)

26 p. 199: Sont-ce des portraits, des études ou des sujets composés que ces deux figures de femme à la fenêtre, dont l’une se trouve à la Dulwich gallery?[…] La jeune femme de la galerie Dulwich repose les deux bras sur le battant inférieur d’une porte. Une autre peinture semblable représente une jeune femme pâle et delicate, portant un bonnet rouge, qui repose le bras gauche sur l’appui d’une fenêtre, tandis que la droite écarte un rideau rouge. (Are these two female figures at a window, one of which is in the Dulwich gallery, portraits, studies or composite subjects? […] The Dulwich Gallery young woman rests both arms on the lower half of a door. Another similar painting shows a pale and delicate young woman, wearing a red cap, resting her left arm on a window frame, and pulling aside a red curtain with her right.) On p. 471 Vosmaer merges Smith’s nos 178 (DPG163) and 532. The latter is now in Chicago (Related works, no. 3e), but the girl in Chicago has no red cap, nor is there a curtain, as described by Vosmaer.

27 The provenances of Smith’s nos 532 and 171 (they mean 178) are combined: ‘Formerly called “Portrait of Rembrandt’s Servant-maid;” this title was given to it by mere caprice, and was not traditional. […] The features of the girl in this picture are very similar to those of Rembrandt. It may therefore be considered as the portrait of one of his relations.’

28 ‘the charming brown-faced Girl at a Window by Rembrandt’.

29 14 pictures of DPG were lent to the NG Board Room from 7 July to 3 Sept. 1989. There was no catalogue.

30 RKD, no. 217306: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/217306 (March 13, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 165, fig. 3, under DPG163; Liedtke 2007, pp. 203–7, no. 46; Liedtke 1995, pp. 91–3, no. 22; Sonnenburg 1995, pp. 61–5 (fig. 83).

31 RKD, no. 293763: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/293763 (June 19, 2020). See also http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/4766abf5.html (June 19, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 166, fig. 4 (where the dimensions of height and width are switched), under DPG163; Williams 2001, p. 187, no. 103; M. Royalton-Kisch in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, pp. 57–8, no. 4; Benesch 1973, iv, p. 186, no. 700, fig. 889; Benesch 1947a, p. 32, no. 143; Benesch 1947b, fig. 143.

32 RKD, no. 215267: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/215267 (June 19, 2020); see also https://collections.mfa.org/objects/33744 (June 21, 2020).

33 Van de Wetering 2017, i, p. 302, no. 194, ii, pp. 584–6, no. 194; Van de Wetering 2015, pp. 584–6, fig. 194; the canvas consists of several pieces and had been glued to panel; RKD, no. 22236: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22236 (19 March 20, 2019); see also https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/5353/woman-bed (June 19, 2020); Williams 2001, pp. 182–4, no. 100 (c. 1645).

34 RKD, no. 3063: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/3063 (21 Dec. 2013).

35 RKD, no. 185028: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/185028 (19 Nov. 2013); Sumowski 1983–94, iv, (c. 1989), p. 2610, no. 1785. According to Ilja Veldman, ‘Victors’ Woman at the Window (or rather Woman Closing the Window) is […] Michal, David’s wife, who sees her husband dancing out of the Ark of the Covenant with delirium of joy (and scantily dressed) blaming [him?], which heralds their separation. Earlier, in the first book of Samuel, she lets David escape from a window’ (email to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 16 June 2020). With many thanks to Ilja Veldman; see Veldman forthcoming – a (in the online version of Saur this was published in December 2020). There is another Victors picture with A Girl at a Window, dated 1642, ill. Williams 2001, p. 188 (fig. 137), then in the Salomon Lilian Gallery, Amsterdam. About this picture she wrote an article that will be published in Simiolus, Veldman forthcoming – b.

36 RKD, no. 234188: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/234188 (June 25, 2020); see also https://kolekcja.zamek-krolewski.pl/en/obiekt/kolekcja/Paintings/query/rembrandt/id/ZKW_3906 (June 25, 2020); Van de Wetering 2017, i, p. 287 (fig. 186), ii, p. 575–6, no. 86; Juszczak & Małachowicz 2013, i, pp. 388–91, 394, no. 264, ii, p. 670, 805; Rembrandt 2006, pp. 306–8 (no. 33; E. van de Wetering); Juszczak & Małachowicz 1998, pp. 54–6, no. 16.

37 RKD, no. 234222: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/234222 (June 25, 2020); see also https://kolekcja.zamek-krolewski.pl/en/obiekt/kolekcja/Paintings/query/rembrandt/id/ZKW_3905 (June 25, 2020); Van de Wetering 2017, i, p. 286 (fig. 185), ii, p. 575–6, no. 85; Juszczak & Małachowicz 2013, i, pp. 391–4, no. 265, ii, p. 805; Rembrandt 2006, pp. 306–8 (no. 34; E. van de Wetering); Juszczak & Małachowicz 1998, pp. 51–4, no. 15.

38 RKD, no. 41138: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/41138 (Nov. 19, 2013); Cavalli-Björkman 2005, pp. 405–8, no. 417; Cavalli-Björkman in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, p. 56, no. 2 (p. 25, colour pl. I).

39 RKD, no. 208170: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/208170 (June 25, 2020; studio of Rembrandt or possibly Carel Fabritius); see also https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.81.html (June 25, 2020); Sumowski 1983–94, vi (1994), p. 3714, no. 2298b (S. van Hoogstraten); Wheelock 1993.

40 RKD, no. 244564: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/244564 (March 13, 2019); Blanc 2008, p. 362, no. P38; Sumowski 1983–94, vi (1994), p. 3714, no. 2298a; C. Brown in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, pp. 56–7, no. 3 (p. 26, colour pl. II).

41 RKD, no. 52041: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/52041 (June 21, 2020); see also https://www.artic.edu/artworks/94840/young-woman-at-an-open-half-door (June 21, 2020; Workshop of Rembrandt van Rijn); Blanc 2008, p. 361, no. P34; Brown, Kelch & Van Thiel 1991, pp. 350–53, no. 72 (C. Brown).

42 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-5-26 (June 21, 2020).

43 RKD, no. 298101: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/298101 (June 24, 2020); see also https://hvrd.art/o/303699 (June 20, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 166, fig. 5, under DPG163; Williams 2001, p. 177, 257, no. 96 (c. 1640–45).

44 Rutgers 2008, pp. 175 (no. 11), p. 180 (fig. 11).

45 RKD, no. 209181: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/209181 (March 20, 2019); Sumner 1993, pp. 31–4; A. Sumner in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, p. 59, no. 5. For other copies by Santerre see also Lesné 1988 and Lesné & Waro 2011.

46 RKD, no. 117409: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/117409 (June 24, 2020); see also https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/joconde/5013M000439 (June 25, 2020). Lossky 1967, pp. 180–81.

47 RKD, no. 293707: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/293707 (June 24, 2020); R. Willard in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, pp. 59–60, no. 6; dated c. 1719 because of the referral to a popular character from the Italian commedia dell’arte; see also RKD, no. 117545: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/117545 (June 24, 2020); Atwater 1989, pp. 1070–71, no. 1150 (after 1735); dated by the BM c. 1759 (without explanation), see https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1874-0808-1825 (June 21, 2020).

48 Oursel 1985.

49 RKD, no. 119863: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/119863 (June 24, 2020); Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, p. 60 (fig.).

50 Sumner 1993, pp. 30–31, fig. 1.

51 This pastel was used as proof of the Scottish provenance of DPG163; Roscam Abbing however argues that in the 1770s the picture was in Paris (see Provenance), where Grenville-Scott could have seen it; Sumner 1993, p. 35 (fig. 9), 60–61, no. 7, who refers to Roscam Abbing on p. 19 in the same catalogue; see also White, Alexander & D’Oench 1983, p. 44, under no. 81.

52 Postle argues that the copy in the Hermitage is not by Reynolds, which is accepted by Reynolds scholars. In the Hermitage catalogues it can be found under ‘Unknown artists: eighteenth–early-nineteenth century’: Dukelskaya & Renne 1990, pp. 163–4. However Reynolds’ Girl leaning on a pedestal (now in a private collection) was painted by Reynolds as a pendant or ‘companion’ for Rembrandt’s Girl: see Mannings & Postle 2000, pp. 585 (no. 2230, i.e. the copy in the Hermitage, 62.9 x 53 cm), 531–2 (no. 2073, Joshua Reynolds, Girl leaning on a pedestal, 75 x 62.2 cm., private collection). Postle argues that the last picture was made by Reynolds after DPG163 in the collection of a Mr Campbell (probably John Campbell, later Baron Cawdor), Mannings & Postle 2000, p. 531. That is not possible, as the Scottish provenance of DPG163 is no longer accepted (see the preceding note).

53 A. Sumner in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, pp. 36 (fig. 11), 62, no. 9.

54 ibid., pp. 62–3, no. 10 (p. 17, colour pl. III).

55 RKD, no. 298132: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/298132 (June 27, 2020); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1861-1109-286 (June 21, 2020). For a later state dated 1814: BM, London, 1852,1009.1266; Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, pp. 63–4, no. 11 (A. Sumner); White, Alexander & D’Oench 1983, p. 44 (under no. 81), p. 142, no. 156 (3 states).

56 https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-jessica-t03887 (June 21, 2020), where several other Rembrandts are mentioned as a source of inspiration; Solkin & Simpson, pp. 150–51, 229, no. 44. However Baker argues that it was Rubens rather than Rembrandt who influenced Turner in this picture: Baker 2009, p. 854.

57 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2010-7081-6963 (June 21, 2020).

58 Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, p. 65, no. 15 (A. Sumner).

59 ibid., no. 14 (A. Sumner).

60 RKD, no. 298146: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/298146 (July 15, 2020); Waterfield in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, p. 64, no. 12 (p. 28, colour pl. IV).

61 Willard in Bomford, Sumner & Waterfield 1993, p. 66, no. 16.

62 ibid., no. 17.

63 Sumner 1993, p. 38, fig. 13.

64 ibid., pp. 39–40, fig. 17, as Sully, copper, 6¼ x 8½ in., 1851. According to RKD, no. 119869 (21 Dec. 2013), Sully made sixteen copies after DPG163 between 1837 and 1866.

65 Sumner 1993, pp. 41–2 (fig. 18); Miller 1992, p. 745 (fig. XVII).

66 Shawe-Taylor & Scott 2007, pp. 68–9, no. 9. A Samuel van Hoogstraten with a man at a window of 1653 in Vienna is also illustrated (p. 68, fig. 32).

67 RKD, no. 32948: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/32948 (June 26, 2020); see also https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/10/collection/404120/self-portrait-in-a-flat-cap (June 26, 2020); Scott & Hillyard 2019, p. 16, 24, 25, 26–7, 112, cat. no. 4.

68 Plender 1993, p. 49.

69 Gersaint 1747, pp. 197–9 (see note 7 above). The two pictures formed a pair from at least 1732 to 1776 (see Provenance); an inscription on the back of the Flora says that it was transferred from panel to canvas in 1765. Sonnenburg 1995, pp. 61–5 (fig. 83); see also Liedtke 1995, pp. 91–3, no. 22.

70 Williams 2001, p. 182.

71 Van de Wetering 2017, i, p. 302, no. 194, ii, pp. 584–6, no. 194 (p. 585: ‘The nature of the life-size image makes it likely that it was a painted decoration on an existing door, and that we have is a trompe l’oeil box-bed scene on a door of an actual box-bed’); Van de Wetering 2015, pp. 584–5.

72 Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 89–128, and Appendix III, pp. 224–39. An essential element is the catalogue compiled by Gersaint for the sale of the collection of Louis-Auguste Angran, Vicomte de Fonspertuis, in 1747 and 1748. After Roger de Piles, it was in the possession of a M. Duvivier, officer and uncle of de Fonspertuis, then of the Polish Count d’Hoym, then of the minister M. de Morville, and and finally of M. de Fonspertuis, who bought it at the sale of M. de Morville. This poses some problems: de Morville died in 1732, before Count d’Hoym, and no Morville sale is known. It must have been the other way round: Count d’Hoym must have acquired the painting from de Morville, Minister of Foreign Affairs, who had been French ambassador in The Hague between 1718 and 1720, when he probably purchased Flinck’s Flora. On Gersaint’s error see Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 167–70.

73 For de Piles’ description of DPG163 in 1708 see note 12.

74 Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 123.

75 Hofstede de Groot 1906; see Roscam Abbing 1999, p. 89.

76 Kris & Kurz 1979, pp. 8–10, 63, as cited by Roscam Abbing 1999, pp. 90, 94.

77 Valentiner 1905, pp. 41, 44, cit. in Williams 2001, pp. 188, 258 (note 8).

78 Wheelock 1993, p. 142. Koslow 1975, p. 429, comes to the same conclusion and suggests that the same girl modelled for that.

79 Cavalli-Björkman 2005, p. 407 (no. 417).

80 ibid.

81 Interestingly one of the later reproduction prints, a lithograph by an unknown artist, is called Paraja, the Mulatta Slave of Valasquez; clearly the maker had also seen in DPG163 traces of African roots of the girl depicted (Related works, no. 6m).

82 For an overview of interpretations see Williams 2001, pp. 188–9, 258, no. 104.

83 Koslow 1975, p. 429.

84 Sumner 1994b. However it had been made very difficult for later authors: who looks at the second edition of an exhibition catalogue of nine years earlier? Consequently this was not seen by Williams 2001, p. 188, and Marieke de Winkel in Rembrandt 2006, p. 328, who still consider that she has a gold chain around her neck, as in Manuth, De Winkel & Van Leeuwen 2019. Koslow thinks it is a string of beads: Koslow 1975, p. 429.

85 As was confirmed in conversation by Edward van Voolen, Curator of the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. However see the suggestion by Ilja Veldman relating to the girl painted by Jan Victors (Related works, no. 2a); according to her she is Michal, the wife of David, from the Old Testament (Samuel 6.14-23; I Chronicles 15:29): see note 35. For the interpretation of DPG163 it could be of interest that the first of all these trompe l’œil girls was possibly an Old Testament heroine. Veldman, on the other hand, argues in her coming article that the later trompe l’œil girls are quite different from those of Victors, Veldman forthcoming – b.

86 At least according to Williams 2001, p. 182. De Winkel in Rembrandt 2006, p. 328, also calls the picture Sarah waiting for Tobias.

87 As stated in Williams 2001, p. 182 (no. 100).

88 In any case it is not the end of a metal (gold or silver) headpiece, which features in some Dutch traditional costumes.

89 Marieke de Winkel in Rembrandt 2006, p. 328.