Peter Paul Rubens DPG264

DPG264 – The Three Graces Dancing

PROVENANCE

?Sir James Thornhill, Cock, 25 Feb. 1734 or 1735 (Lugt 433), lot 18 (‘The Graces, a Sketch by Rubens’), for £3 4s. to ‘Pond, Houlditch’;1 ?Houlditch sale (died 2 Dec. 1736), Langford, 5 March 1760 (Lugt 1086), lot 55 (‘Rubens; Women dancing’); transaction unknown;2 ?John Bertels or Sir Gregory Page, 1783: their combined sale, London, King Street, Great Room, 9 May 1783 (Lugt 3573), lot 43 (‘Rubens – The three graces. Rubens has aptly united in this group, the elegance of the Antique to his colouring’);3 ?Isaac Jemineau sale, Christie’s, 27 Feb. 1790 (Lugt 4537; under ‘Pictures consigned from France’), lot 16 (‘Rubens – The Graces, a small fine sketch’;4 ?London, European Museum (‘Fourth Exhibition and Sale by Private Contract at the European Museum’), (?)December 1792, lot 264 [manuscript note on copy of catalogue at Getty Provenance Index: ‘copy small, like […?] revered [???]’;5 Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 15, no. 136 (Middle Room 2nd Floor / no. 14, Sketch of the Three Graces, in one colour – P[anel] Rubens’; 4' x 3').

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 12, no. 198 (‘CENTRE ROOM – North side; The Graces; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 391, no. 198;6 Cat. 1820, p. 12, no. 198 (The Graces; Rubens); Patmore 1824b, pp. 59–60, no. 197;7 Cat. 1830, p. 12, no. 240 (The Three Graces (a Sketch); Rubens); Cat. 1831–3, p. 12, no. 240;8 Jameson 1842, ii, p. 482, no. 240;9 Denning 1858, no. 240;10 not in Denning 1859; Lavice 1867, p. 180 (Rubens, no. 1);11 Sparkes 1876, pp. 153–4, no. 240 (A Sketch); Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 142, no. 240;12 Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), pp. 100, under no. 616 (a disappeared original, Related works, no. 15a.Ic; DPG240 is doubtful);13 Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 72, no. 264; Dillon 1909, p. 215; Cook 1914, p. 166, no. 264;14 Cook 1926, p. 156, no. 264; Cat. 1953, p. 35, no. 264; Müller Hofstede 1965, pp. 169 (fig. 9 ), 170, 180 (note 33) (Rubens, c. 1631–2); Shaw 1976, i, p. 333, under no. 1371 (Related works, no. 1) [2], fig. 106; Murray 1980a, p. 114; Murray 1980b, p. 25; Held 1980, i, pp. 326–7, no. 239, p. 355, under no. 264 (Related works, no. 21), fig. 64, ii, pl. 249 (c. 1625–8); Logan 1981, p. 515 (earlier than 1625–8?);15 Jaffé 1983b, p. 118; Freedberg 1984, pp. 240–41 (note 3), fig. 174, under no. 53b (Related works, no. 16a); Cleaver, White & Wood 1988, p. 42, under no. 9 (Related works, no. 1) [2]; Jaffé 1989, p. 351, no. 1224 (c. 1636); Bodart 1990, p. 128, under no. 44 (Related works, no. 4f.II of DPG43); not in Mertens 1994; Beresford 1998, p. 211; Vergara 2001, pp. 64–5 (fig. 37); Tyers 2014, pp. 37–9; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 203–5, 214; McGrath 2016, i, p. 452, 454 (note 34), ii, fig. 393; RKD, no. 295009: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295009 (Sept. 1, 2019). Van Beneden forthcoming.

EXHIBITIONS

Houston/Louisville 1999–2000, pp. 134–5, no. 39 (D. Shawe-Taylor); Greenwich, Conn./Cincinnati, O./Berkeley, Calif. 2004, p. 184–7, no. 24 (M. E. Wieseman).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Three-member oak panel with a pronounced convex warp. The panel is likely to have originally been constructed from two members; the upper board has been cut in a traverse jigsaw pattern around the heads of the three Graces and subsequently replaced with a different piece of wood [1]. Dendrochronology indicates that the lower board matches eastern Baltic reference data. The latest ring identified was 1609, suggesting that with the minimum expected number of sapwood rings the tree was felled after 1617. The other boards could not be matched to reference data and could not be dated. The lower left edge is slightly chipped, and there is a horizontal crack through the left Grace’s torso, just below her breast, and another crack from the top left corner towards her head. The jigsaw join is primed on the verso with white gesso. Beneath the main grisaille image on the front of the panel is a white ground, with grey imprimatura; the paint and ground are raised in some areas, such as the bottom left and top right corners and above the figures’ heads, but appear secure. There is some faint abrasion in the dark grass to the left of the Graces. Some old retouchings on the left Grace are slightly discoloured and grey, and the in-painting over the jigsaw join appears darkened and slightly matt. There are drying cracks around the heads. Overall this painting is in good condition. Previous recorded treatment: 1938, frame reglazed; 1945, conserved, Dr Hell.

RELATED WORKS

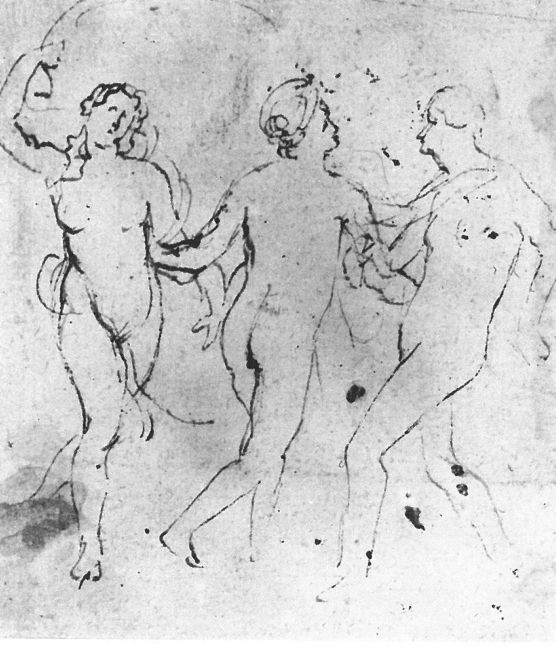

1) (preparatory drawing?) Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, pen and brown ink, 105 x 95 mm. Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, 1373 [2].16

Designs for silver, ivory and sculpture

see also Related works, no. 9b

2a) (grisaille, modello for a silver basin and ewer) Peter Paul Rubens, The Birth of Venus, c. 1632–3, panel, 61 x 78 cm. NG, London, NG1195 [3].17

2b) Jacob Neeffs after Peter Paul Rubens, Design for a basin (with the Birth of Venus) and ewer (with the Judgement of Paris), inscriptions in Latin indicating that basin and ewer were made for Charles I (?), etching, 379 x 477 mm. Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, PK.OP.19103.18

2c) Theodoor Rogiers I, Basin (with Susanna and the Elders) and ewer (with Venus crowned by the Three Graces), 1635–6, silver, 60 x 45 cm (basin); h 37, d 15 cm (ewer). King Baudouin Foundation, on loan to the Rubenshuis, Antwerp.19

2d.I) (grisaille, modello for an ivory salt cellar, 2d.II and for 2d.IV) Peter Paul Rubens, Triumph of Venus, oil, over black chalk indications, on panel, 34.5 x 48.5 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, PD.7–2012 [4].20

2d.II) (preparatory drawing) Peter Paul Rubens (previously Anthony van Dyck), Venus with Nereids, c. 1627–8, pen and brown ink on light brown paper, 272 x 250 mm. BM, London, 1920,1012.1 (recto).21

2d.III) Georg Petel and Jan Herck I after Peter Paul Rubens (2d.I), Salt cellar with the Triumph of Venus, signed I.P.F., 1628, ivory and silver gilt, h 43.8, d 12.5 cm. Royal Collections, Stockholm, S.S.143 [5].22

2d.IV) (in reverse) Pieter de Jode II after Peter Paul Rubens (2d.I), The Birth of Venus – Venus Orta Mari (Venus rose from the sea), engraving, 400 x 524 mm. BM, London, 1891,0414.860.23

2e) Peter Paul Rubens, Albert I, Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation, modello for a statue, panel, 38.5 x 21.5 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, 510/2.24

Older examples – Graces standing and seated

3a) Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, The Three Graces, marble. Biblioteca Piccolomini, Cathedral, Siena.25

3b) Roman, Three Graces, marble, 105 cm. Louvre, Paris, Ma 287 (MR 221).26

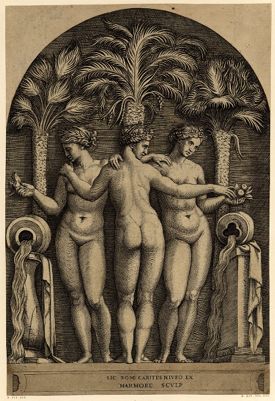

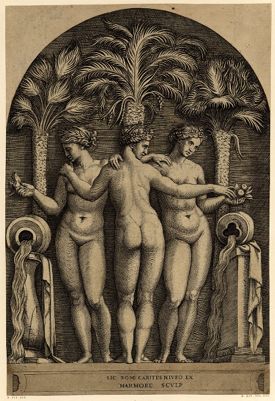

3c) Marcantonio Raimondi, after an Antique relief, The Three Graces, c. 1510–27, Latin inscriptions, engraving, 321 x 221 mm. BM, London, H,2.91 [6].27

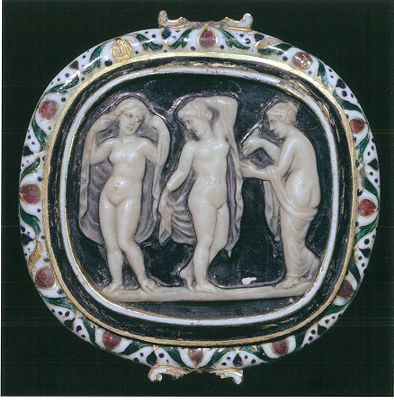

3d) Roman cameo, The Three Graces, two-layered sardonyx in enamel frame, 3 x 3 cm. Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Babelon 65 [7].28

4) Raphael, The Three Graces, 1504–5, panel, 17 x 17 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly, PE 38.29

5a) Giulio Romano and others after Raphael, Group of Three Graces seated, fresco. Loggia of Psyche, Villa Farnesina, Rome.30

5b) Marcantonio Raimondi after Raphael (5a), The Three Graces seated, 1517–20, engraving, 308 x 207 mm (part of the series of Chigi Gallery spandrels in the Villa Farnesina, Rome). BM, London, 2006,U.412.31

5c) Peter Paul Rubens (or studio replica?) after Raphael, The Ascent of Psyche to Olympus, c. 1625–8, panel, 85 x 72.5 cm. Duke of Sutherland collection, Mertoun, St Boswells (Roxburghshire), on loan to the NGS, Edinburgh, NGL 002.94.32

6) Peter Paul Rubens after caryatids designed by Primaticcio at Fontainebleau (c. 1545), Three Women holding Garlands, c. 1620–25, red chalk and brush, heightened with white (now yellowed) bodycolour, a piece of paper affixed at both the upper and lower left, 269 x 253 mm. BvB, Rotterdam, V 6.33

7a) Sandro Botticelli, La Primavera, 1477–82, tempera on panel, 203 x 314 cm. Uffizi, Florence, P254.34

7b.I) Jacopo Tintoretto, The Three Graces and Mercury, 1577–8, canvas, 146 x 155 cm. Anticollegio, Palazzo Ducale, Venice.35

7b.II) Workshop of Domenico Tintoretto, Venus and Mars with Cupid and the Three Graces in a Landscape, 1590–95, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 142.8 cm. Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, 1929.914.36

7c) Jacob Matham after Hendrick Goltzius, The Three Graces, 1588, engraving, 297 × 208 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-27.314.37

Standing Graces

8a) Studio of Peter Paul Rubens, Three Graces, c. 1635–7, black and red chalk washed with brown, 282 x 250 mm. University Library, Warsaw, zb.d. 1275 (verso).38

8b.I) Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, 1639, panel, 220.5 x 182 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1670 [8].39

8b.II) Pieter de Jode II after 8b.I, The Three Graces, Latin inscriptions (Horace), engraving with etching, 483 x 348 mm. BM, London, 1841,0809.47.40

8b.III) Peter Paul Rubens, Horrors of War, 1638, canvas, 206 x 342 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Florence, 1912, 86.41

The Three Graces carrying (a basket)

9a) Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, red chalk heightened with white bodycolour, 267 x 170 mm. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, Princes Gate Bequest, D.1978.PG.66.42

9b) Georg Petel, The Three Graces, c. 1620, gilt bronze, 30.5 x 19.7 x 5.2 cm. MFA, Boston, 1976.842.43 (See also Related works, nos 2d.I and III)

9c) Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, c. 1620–24, panel, 119 x 99 cm. Gemäldegalerie der Akademie, Vienna, 646 [9].44

9d.I) Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel II, The Three Graces with a Basket of Roses, canvas (originally on panel), 111 x 64 cm. National Museum, Stockholm, NM 601.45

9d.II) After Peter Paul Rubens (9d.I), The Three Graces, black chalk, indented for transfer, laid down, 377 x 248 mm. BvB, Rotterdam, MB 5125.46

9e) Peter Paul Rubens, Nymphaeum with a Statue of Venus, after 1636, inscribed P. P. Rubens (in another hand), black chalk, pen in grey, brush in brown, 302 x 485 mm (recto). Staatliche Museen, Berlin, KdZ 2234.47

Other subjects

10) Peter Paul Rubens, The Judgement of Paris, c. 1597–9, panel, 133.9 x 174.5 cm. NG, London, NG6379.48

11a) (modello for 11b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Education of Maria de’ Medici, panel, 49.5 x 39.4 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 92.49

11b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Education of Maria de’ Medici (part of the Medici cycle), 1621–5, canvas, 394 x 295 cm. Louvre, Paris, 1771.50

Three Graces crowned by Cupids

12) Peter Paul Rubens, Three Graces with another Figure, c. 1635, pen and brown ink, over red chalk, on buff paper, 214 x 201 mm. BM, London, 1981,0725.31.51

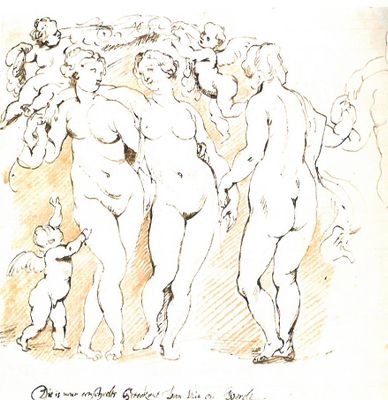

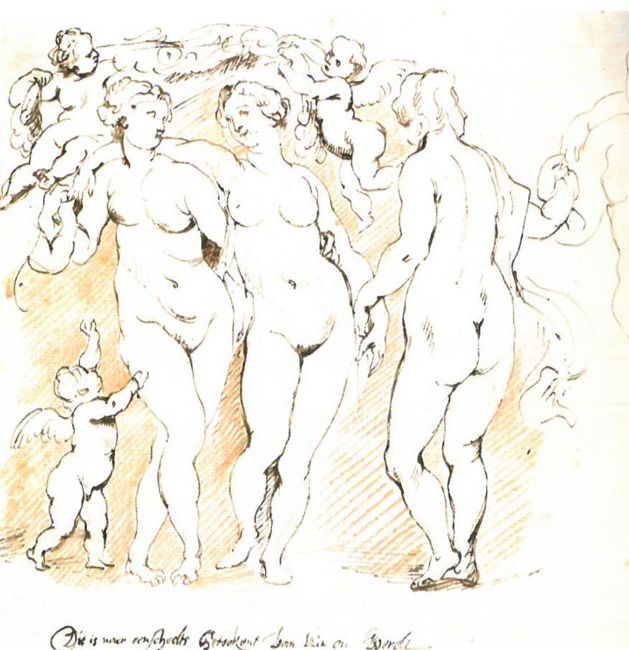

13) Rubens’s Cantoor (Willem Panneels), The Three Graces, 1628–30, Dit is near een Schedts Geteekent Van Wit en Swerdt (This is drawn after a sketch in white and black), pen, brown ink, black and red chalk, 210 x 215 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, Rubens’s Cantoor [10].52

14a.I) (bozzetto for 22a; see also 11b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, c. 1630, panel, 46.5. x 34.5 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Florence, 1890, no. 1165.53

14a.II) Jean Massard after Jean Baptiste Wicar after Peter Paul Rubens (14a.I), The Three Graces, inscriptions, etching and engraving, 270 (trimmed) x 201 mm. BM, London, 1891,0414.872 (part of Mongez 1789–1807).54

15a.Ia) Studio of Peter Paul Rubens, Young Women led forward by Putti, c. 1635–7, black and red chalk washed with brown, 282 x 250 mm. University Library, Warsaw, zb.d.1275 (recto).55

15a.Ib) (modello of 15a.Ic, grisaille) Peter Paul Rubens, Young Women led forward by Putti, c. 1633–5, panel, 30 x 32 cm. Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, Milan, 1275.56

15a.Ic) Peter Paul Rubens, Three Graces, painting, present wherebouts unknown (see 15a.Ia–b; II and III).57

15a.II) Remoldus Eynhoudt or Cornelis Schut I after Peter Paul Rubens, Three Graces with Five Cupids, etching, 233 x 253 mm (paper). Teylers Museum, Haarlem, KG 17669 [11].58

15a.III) Maria Cosway after Peter Paul Rubens (15a.Ic), Helena Forman conducted to the Temple of Hymen, 1807, inscriptions, etching and aquatint, 348 x 301 mm. BM, London, 1865,0311.177.59

Dancing and moving Graces, nymphs, nereids, the Blessed, and peasants

16a) Peter Paul Rubens, studies for Groups of the Blessed, point of the brush and brown ink over red chalk, 306 x 415 mm. Private collection, England.60

16b) Peter Paul Rubens (?) and Jan Boeckhorst, The Assumption of the Righteous or Blessed, panel, 119 x 93 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 353.61

17a) (modello for 17b) Peter Paul Rubens, The Birth of Venus, c. 1638, panel, 26.5 x 28.3 cm (one of twelve oil sketches for the Torre de la Parada). KMSKB, Brussels, 4106.62

17b) Cornelis de Vos, The Birth of Venus, canvas, 187 x 208 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1862.63

18) Peter Paul Rubens, Feast of Venus, c. 1636–7, canvas, 217 x 350 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 684.64

19a) Peter Paul Rubens, Dancing Peasants (recto), Feasting Peasants (verso), c. 1630–32, black chalk and pen and brown ink and a few traces of red chalk (recto), pen and dark brown ink over preliminary drawing in black chalk (verso), 595 x 512 mm. BM, London, 1885,0509.50.65

19b) Peter Paul Rubens, Feasting and Dancing Peasants (The Kermesse or The Village Wedding), c. 1630–32, panel, 149 x 261 cm. Louvre, Paris, 1797.66

19c) Peter Paul Rubens, Dancing Peasants and Mythological Figures, c. 1630–35, panel, 73 x 106 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1691.67

19d) Anonymous Flemish painter after Peter Paul Rubens, Moses, Aaron, and Miriam and other Women celebrate the Crossing of the Red Sea, c. 1635–8, panel 54.5 x 79 cm. Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, 1886.68

20) Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snijders, Diana and her Retinue, surprised by Satyrs, 1639, canvas, 128 x 314 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1665.69

21) Copy after (or studio of) Peter Paul Rubens, Silenus with Bacchic Revellers, c. 1625–8, panel, 48.1 x 72 cm. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, Samuel Courtauld Bequest, P.1948.SC.384 [12].70

Gerard van Opstal’s ivories after Rubens

22a) Gerard van Opstal after Peter Paul Rubens (14a.I), The Three Graces, ivory relief, present whereabouts unknown, stolen from Musées Royaux d’art et d’histoire, Brussels, 2169.71

22b) Attributed to Gerard van Opstal, Silver cup (German) and ivory base with a bacchanal (or the Three Graces?), silver and ivory, total h 50.5 x w 25 cm, base d 14 cm. Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas, Madrid, CE17828.72

22c) Attributed to Gerard van Opstal, Carved ivory tankard sleeve with the Three Graces, ivory and gilt bronze, h 35 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé sale, Christie’s, Paris, 23–25 Feb. 2009 (Sale 1209), lot 570.73

DPG264

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, c. 1636

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG264

1

Diagram of panel structure of DPG264

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, 1610-1630

Oxford (England), Christ Church Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 1373

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Birth of Venus, 1630-1631

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. 1195

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Triumph of Venus, before or in 1628

Cambridge (England), Fitzwilliam Museum, inv./cat.nr. PD.7-2012

5

Georg Petel and Jan van Herck after Peter Paul Rubens

Salt cellar with the Triumph of Venus, dated 1628

Stockholm, private collection Royal Collections Sweden, inv./cat.nr. S.S.143

6

Marcantonio Raimondi

Three Graces, c. 1510-1527

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. H,2.91

7

Anonymous, Roman

Three Graces

precious stone, enamel (coating) 30 x 30 mm

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), inv. Babelon 65

8

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, c. 1638

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P001670

9

Peter Paul Rubens

Three graces with a basket of roses, c. 1626

Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, inv./cat.nr. 646

10

Willem Panneels after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, 1628-1630

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark

11

Cornelis Schut (I) after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces with five cupids

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. KG 17669

12

studio of Peter Paul Rubens

Silenus with Bacchic Revelers

London (England), Courtauld Institute of Art, inv./cat.nr. P.1948.SC.384

Except for Rooses in 1890 and Burchard in his notes, no one has doubted Rubens’s authorship.74 Held suggested a date of c. 1625–8 and Jaffé c. 1636. While the picture would appear to be a preliminary study, this grisaille or rather brunaille has not been linked to any surviving large-scale painting or tapestry. It could be that a drawing of the Three Graces in Christ Church, Oxford, represents Rubens’s first thoughts for DPG264, but doubts have been raised about a connection between the two, and indeed whether the drawing is by Rubens (Related works, no. 1) [2].75

The panel shows the way of working typical of the master: he was always rearranging his compositions and the panels on which he made his grisailles, bozzetti and modelli. The way the panel is constructed looks like a jigsaw puzzle [1]. In the catalogue of the exhibitions in Houston and Louisville in 1999–2000 Desmond Shawe-Taylor suggested – as did Betsy Wieseman in 2004 – that the absence of colour and the relief-like composition might indicate that this was originally a study for an engraving or a piece of silverware, like the modello in the National Gallery for the silver basin supposedly made for Charles I (Related works, nos 2a–b) [3].

Elizabeth MacGrath has argued that most of Rubens’s depictions of the Three Graces (or Charities, see below) relate to designs for sculpture.76 Later she proposed that this sketch was probably a design for an ivory carving (in the round) rather than for a silver relief.77 The figures would, if so, come together around a circular object. It could be objected that studies by Rubens for three-dimensional objects are in general more elaborate and the figures more sculptural (see below) than in this example. According to Nico Van Hout DPG264 is unfinished, and that is why it does not look like other studies.78 McGrath considers it to be a ‘slight sketch’, maybe even unfinished, that was later strengthened and the figures set within a landscape. She also proposes that what might have been the beginning of a garland was turned into a tambourine by a later hand. This raises the question whether there was something above the heads of the Graces before the panel was drastically cut down (see Technical Notes) [1], since putti and garlands are common features of Rubens’s sketches of Graces.

An example of a model for a three-dimensional object is Triumph of Venus, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. That is a design by Rubens for an ivory salt cellar to be made by Georg Petel (1601/2-1634), who was at the time working in Rubens’s studio. The salt cellar was made for Rubens’s own use (Related works, nos 2d.I–III) [4]. According to Burchard in 1950 there must have been sketches by Rubens and even terracotta models by Petel between the Cambridge modello and the ivory carving.79 Moreover, the fact that there is no colour in the sketch does not rule out the possibility that it was a design for a painting: the grisaille with Venus mourning Adonis (DPG451) does not have much colour (only some spots of red and a blue sky), and a large scale version does exist (in Jerusalem: see under DPG451, Related works, no. 1a; Fig.). Other modelli that we know were designs for sculpture are the decorations that Rubens devised in 1635 for the Joyous Entry of the Cardinal Infante Ferdinando to Antwerp as governor of the Spanish Netherlands in 1635: the modello for Albert I, Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation, in the Hermitage (Related works, no. 2e), features a niche, which gives an impression of sculpture. The later sculptor Gerard van Opstal (1605–68) used Rubens’s models, such as his bozzetto in the Palazzo Pitti, for an ivory relief now stolen (Related works, no. 14a.I and 22a). He was a pupil and then son-in-law of the sculptor Johannes van Mildert (1588–1638), who worked with Rubens on the Joyous Entry of the Cardinal Infante. How Van Opstal would use Rubens’s modelli is not known: he was not the master’s pupil, nor were his sculptures executed under Rubens’s supervision, and stylistically his Graces do not look like Rubens’s models (Related works, nos 22a–c). It seems unlikely that Rubens knew Van Opstal was to use his sketches.80

The motif of the Three Graces goes back to Antiquity; we find them both in texts and in sculpture.81 DPG264 depicts the Graces – sometimes called Euphrosyne, Thaleia and Aglaia – engaged in a dance, with one of them playing a tambourine to keep time. Held (1980) pointed out that the source is likely to be Horace (Odes, I.iv, 6–7), who, in his description of the transition from winter to spring, mentions the dancing of Jupiter’s three daughters and describes them as companions of Venus. Held convincingly argued that the intertwined arms of the women would suggest that the subjects were the Graces rather than the Horae. That view is supported by the circular temple which might be dedicated to Venus in the background to the left, if that part is indeed by Rubens and not a later addition. The Graces are also known to have had temples. Balis in 2006 gives an overview of the Classical and Renaissance texts where the Graces appear, with negative as well as positive connotations.82 Held also suggested that the symmetrical arrangement of the figures may have been influenced by Servius’s commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid (I.720), known in the Renaissance through a bastardized version. It is not clear whether the Graces here are meant as harbingers of spring or as messengers of harmony and peace (or both?). In only one case do we know what Rubens meant with the Three Graces, in the late picture The Horrors of War (Related works, no. 8b.III): in a letter to Justus Sustermans (1597–1681), court painter of the Medici in Florence, Rubens explained that he showed Mars trampling le belle lettere ed altre galanterie, in other words war is bad for the arts and letters.83

It is not likely that he had this idea in mind when composing DPG264. The Three Graces here have more in common with the wild dancers that Rubens depicted in the Feasting and Dancing Peasants on two sides of a drawing in the British Museum and in two paintings, Feasting and Dancing Peasants in the Louvre and Dancing Peasants and Mythological Figures in the Prado (Related works, nos 19a–c), and with the struggling nymphs that try to defend themselves against the satyrs in the 1639 painting in the Prado (Related works, no. 20). The nymph in the centre of a bacchic scene in a painting in the Courtauld Institute dated to the mid-1620s (Related works, no. 21) [12], thought to be a copy after Rubens or a work of his studio, was associated by Held in 1980 with the central figure in DPG264.The way in which she holds her right arm is very similar. There are differences, as well: she is leaning to the left, while the Grace in the middle of DPG264 is more upright, and their heads are turned differently. The nymph on the right is holding a tambourine as well as the left Grace in DPG264. The clothed women dancing in celebration of the Crossing of the Red Sea in a picture in Karlsruhe show some similarities with the Graces – one is even holding a tambourine – although the authorship of that painting has been much debated (Related works, no. 19d). For other dancing and otherwise moving groups see below.

In general the Three Graces in Antiquity are depicted statically, the central one with her back to us, and with their arms intertwined, as in the groups in Siena and the Louvre (Related works, nos 3a–b). This Antique form was diffused through a print by Marcantonio Raimondi (Related works, no. 3c) [6]. Raphael made a painting that is clearly based on such Antique statues (Related works, no. 4); he shows the Graces with apples in their hands. Rubens knew those well-known examples and Raphael’s seated Graces in the Loggia of Psyche in the Villa Farnesina in Rome, which were also known through prints (Related works, nos 5a–b). He quoted Raphael’s group quite literally in a painting now in Mertoun House (Related works, no. 5c). He was also drawn to the stucchi of elongated women holding garlands by Francesco Primaticcio (1504–70) in Fontainebleau, as shown in a drawing now in Rotterdam (Related works, no. 6). He had probably not seen the dancing if stately Graces in the Primavera by Sandro Botticelli (1444/5–1510), since that picture was in a villa outside Florence (Related works, no. 7a).84 Tintoretto’s composition of the Graces with Mercury in the Doge’s Palace in Venice would probably have been more accessible to him (Related works, no. 7b.I);85 here they seem to have been sitting and just beginning to stand up.

During his long career Rubens made many variations on the theme of three nude women where the inspiration of predecessors shines through to a greater or lesser extent – chiefly the Three Graces, but also Venus, Minerva and Juno in the Judgement of Paris. What Rubens is doing in DPG264 is attempting to depict essentially the same woman from three angles simultaneously. In that he was competing directly with Titian’s mythological poesie painted for Philip II a century earlier, that he had seen during his visits to the Spanish court.86 Rubens’s groups are either just standing or carrying an object, with the central one seen either from the front or from the back. There are also groups with nude women in different contexts (mythological or biblical) dancing or reaching out.

Closest to the Antique groups are the standing Three Graces, with the central one seen from the back. Rubens made some compositions of this type rather late in his career: the drawing in Warsaw is dated c. 1635 (Related works, no. 8a) and the Prado picture c. 1636–8 (Related works, nos 8b.I–II) [8].

Earlier, in the 1620s, Rubens composed scenes with the Three Graces carrying something above their heads, changing them almost into caryatids (though the things are held up in their hands, not supported on their heads). In a drawing in the Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery the figures are similarly posed, with the central one seen from behind (Related works, no. 9a), but sometimes the central one is seen from the front. Rubens owned a cameo with the Three Graces where the central one is seen frontally, as is the left one, and the right one is seen from behind (Related works, no. 3d) [7]. Rubens compositions with the central Grace seen from the front influenced the work of Georg Petel, a German sculptor who worked in Rubens’s studio in the 1620s.87 A bronze relief by him with the Three Graces has largely survived and is in Boston (Related works, no. 9b). Rubens made designs for the Petel group, where the Graces are carrying a basket of flowers. According to Scholten, pictures in Vienna and Stockholm (Related works, nos 9c [9]; and 9d.I) are inspired by Petel’s relief.88 In a drawing related to the late Feast of Venus in Vienna (Related works, nos 9e and 18) the group carry a fountain above their heads.

Even earlier is the Judgment of Paris in the National Gallery, London, which according to David Jaffé was painted when Rubens was still in Antwerp, before he went to Italy (Related works, no. 10). Some twenty years later Rubens resumed his variations on the theme of three nude women in one of the pictures in the Medici cycle for the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris: in The Education of Maria de’ Medici he depicts the Three Graces, with the central one seen from the front and the right-hand one seen from the back, slightly from the side (Related works, nos 11a–b). According to Bodart in 1990, that group is related to the bozzetto of the Three Graces in the Palazzo Pitti (Related works, no. 14a.I), the one that was later used by Gerard van Opstal for one of his ivory objects (Related works, no. 22a; see above). The Pitti bozzetto includes putti, which do not feature in the Medici picture.

The Three Graces appear with putti in a sketch in the Rubens Cantoor by Willem Panneels, probably after a composition by Rubens. The putti are walking on the ground, flying in the air and putting a crown on the head of the Grace in the middle (Related works, no. 13) [10]. The drawing by Rubens in London was probably an earlier version of this (Related works, no. 12). The same putti appear, with the three women completely dressed, in a now lost picture by Rubens (Related works, no. 15a.Ic) that we only know from the modello in Milan and the prints by Remoldus Eynhoudt or Cornelis Schut I and Maria Cosway (1760–1838) (Related works, nos 15a.Ib and 15a.II–III) [11]. In 1890 Rooses related this lost picture to DPG264. It is questionable whether he was right. In Warsaw there is a (preparatory?) drawing for this vanished picture with three richly dressed young women (Related works, no. 15a.Ia) on one side and on the other side a group which is clearly the Three Graces (Related works, no. 8a). At one point for Rubens the subjects were related, at least physically, on the verso and recto. In these works with putti crowning the Graces the central figure is seen frontally; the Grace or woman on the right is now seen from behind (or from the side; Related works, nos 12–15). This position of the Graces is similar to that in Rubens’s Antique cameo, though in the cameo there are no putti with crowns (Related works, no. 3d) [7].

We find similar groups of figures reaching out and/or dancing in depictions of the Blessed, as in the picture in Munich of the Assumption of the Righteous (Related works, nos 16a–b). We see a comparable group in the Birth of Venus in the modello for a silver basin in the National Gallery, c. 1630–31 (Related works, no. 2a) [3] and the later version in Brussels for the Torre de la Parada (1638), after which Cornelis de Vos (c. 1584–1651) made a painting, now in the Prado (Related works, nos 17a–b). Behind Petel’s ivory group of Venus and the Nereids now in Stockholm (c. 1627–8; Related works, no. 2d.III) [5] are at least one drawing by Rubens, in the British Museum, and the modello in the Fitzwilliam Museum (Related works, nos 2d.I–II) [4].

The few notes that were written about DPG264 at the beginning of the 19th century do not show much appreciation by visitors and authors. The Graces were seen as ‘fine fat white pork’ and ‘vraies Flamandes’.89 But the small scale of the Graces protected them from too harsh judgements, unlike the much larger Venus in DPG285.

DPG264

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, c. 1636

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG264

1

Diagram of panel structure of DPG264

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, 1610-1630

Oxford (England), Christ Church Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 1373

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Birth of Venus, 1630-1631

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. 1195

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Triumph of Venus, before or in 1628

Cambridge (England), Fitzwilliam Museum, inv./cat.nr. PD.7-2012

5

Georg Petel and Jan van Herck after Peter Paul Rubens

Salt cellar with the Triumph of Venus, dated 1628

Stockholm, private collection Royal Collections Sweden, inv./cat.nr. S.S.143

6

Marcantonio Raimondi

Three Graces, c. 1510-1527

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. H,2.91

7

Anonymous, Roman

Three Graces

precious stone, enamel (coating) 30 x 30 mm

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), inv. Babelon 65

8

Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, c. 1638

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P001670

9

Peter Paul Rubens

Three graces with a basket of roses, c. 1626

Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, inv./cat.nr. 646

10

Willem Panneels after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces, 1628-1630

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark

11

Cornelis Schut (I) after Peter Paul Rubens

Three Graces with five cupids

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. KG 17669

12

studio of Peter Paul Rubens

Silenus with Bacchic Revelers

London (England), Courtauld Institute of Art, inv./cat.nr. P.1948.SC.384

Notes

1 Sir James 1943a, p. 135; Sir James 1943b (for the Thornhill auction).

2 GPID (25 Aug. 2020).

3 GPID (7 June 2014). Sir Gregory Page is not mentioned.

4 Previous publications on DPG264 have suggested that in 1790 the picture was offered for sale from the ‘Isaac Jermineau’ collection. According to the sale catalogue in the NAL, the owner was Isaac Jemineau, who was appointed British Consul in Naples in 1753. According to GPID (7 June 2014) this was not a painted sketch but a drawing, which seems to contradict the heading ‘Pictures consigned from France’.

5 GPID (24 Dec. 2020).

6 ‘SIR P. P. RUBENS. The three Graces dancing, a Sketch.’

7 ‘A sketch of a similar character with the above [Van Dyck DPG73], in point of the spirit which it exhibits and the talent which it indicates; but the subject is treated with much less of appropriate feeling, and altogether without that grace which should be the distinguishing character of it. Call it, however, by any other name than the Graces, and it could not be open to this objection.’

8 After the titles of nos 239, 240 and 241 (and before the names of the painters) between 1831 and 1833 E. (or C?) Carson wrote ‘three (?) fat white pork’. Since both 239 (DPG192 by Cuyp) and 241 (DPG168, The Mill by Ruisdael) are landscapes, where definitely no pigs are depicted, it is most likely that this not very complimentary remark refers to the Three Graces (no. 240).

9 ‘A small sketch en grisaille. The large picture of this subject was in the collection of Rubens when he died, was bought (according to Michel’s ‘Vie de Rubens’) for the King of England, and is said to be now in the royal collection at Madrid. Another sketch, en grisaille, is at Florence, There are engravings by P. de Jode and Massard.’ See Related works, nos 8b.II and 14a.II.

10 642 ‘“The large picture of this subject was in the collection of Rubens when he died. Was bought (according to Michel’s Life of Rubens) for the King of England, and is said to be now in the royal collection at Madrid. Another sketch en grisaille is at Florence. There are engravings by P de Jode and Massard” Mrs Jameson.’

11 Les trois Graces (petite dimension). L’une est de profil, la tête tournée à notre droite; celle du milieu est vue de dos. La troisième regarde la première et s’offre à nous de face. Toutes trois sont nues. Ce sont des vraies Flamandes. Joli esquisse d’une teinte blanche [sic]. (The Three Graces (small). One is depicted in profile, her face turned to our right; the middle one is seen from behind. The third one looks at the first and offers herself to us frontally. All three are naked. They are real Flemish women. Nice sketch in a white [sic] colour.)

12 ‘Grisaille. […] The artist seems to have been inspired for this composition by Raphael’s representation of the same subject […] now in the Earl of Dudley’s Collection. It is of about the same size.’

13 pièce douteuse. Imitation des Trois Grâces de Raphaël, dans la collection du comte de Dudley (doubtful piece. Imitation of the Three Graces by Raphael, in the collection of the Earl of Dudley).

14 ‘Rubens seems to have been inspired for this composition by Raphael’s representation of the same subject, in the Duc d’Aumale’s collection; so that we have the Three Graces à l’Italienne at Chantilly, and à la Flamande at Dulwich.’

15 The related drawing in Christ Church (Related works, no. 1) is stylistically related to the compositional studies for the Medici-cycle: ‘Held’s date of c. 1625–8 for the sketch may thus be somewhat on the late side.’

16 RKD, no. 295352; : https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295352 (Aug. 20, 2020); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 203, fig. 31, under DPG264; Cleaver, White & Wood 1988, pp. 42–3, no. 9; Shaw 1976, i, p. 333, no. 1373, pl. 809: ‘The central figure nearly corresponds, but in the reverse direction.’ Held seems to have thought that this drawing was made by Van Dyck, according to McGrath (undated typescript, p. 13 (note 39); DPG264 file). She herself thinks it is difficult to maintain that there is a connection between the drawing and DPG264, and she is not convinced that the drawing is by Rubens.

17 RKD, no. 197520: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197520 (July 15, 2019); see also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-the-birth-of-venus (July 15, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 189–91, no. 59 (F. Lammertse); Seelig 2017, p. 99–101 (fig. 3.5); Healy 1997, pp. 91–9, 190–94, 291 (fig. 113); Jaffé 1989, p. 319, no. 1000 (c. 1630–31); Held 1980, i, pp. 355–8, no. 265, ii, pl. 258, col. pl. 17 (1630–31); Martin 1970, pp. 187–93 (1630–31).

18 Seelig 2017, p. 99–101 (fig. 3.6), 113 (note 61); Nys 2006, p. 232, no. 181; Healy 1997, pp. 91–4, 231 (pl. 5); Held 1980, i, p. 357; Martin 1970, pp. 189, 191, 193 (note 45).

19 Seelig 2017, p. 99–105, 113 (note 61), 114 (note 73), pl. 7; Nys 2006, pp. 233–4, no. 182; Fuhring 2001.

20 RKD, no. 295199: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295199 (Oct. 8, 2019); see also https://webapps.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/explorer/index.php?oid=187525 (July 15, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 48, fig. 26; Seelig 2017, p. 107–9 (fig. 3.10); Jaffé 1989, p. 303, no. 897 (1627–8); Rowlands 1977, p. 130, no. 175; Held 1980, i, pp. 358–61, no. 266, ii, pl. 257; Burchard 1950, pp. 8 (fig.), 18–19, no. 16.

21 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1920-1012-1 (Aug. 2, 2020); Büttner & Heinen 2004, pp. 280–81, no. 69 (U. Heinen).

22 RKD, no. 295554: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295554 (Oct. 10, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 49, fig. 27; Seelig 2017, pp. 107–9 (fig. 3.9); Krempel 2007, pp. 27, 64–5 (figs), 153, cat. 15 (with further literature); Büttner & Heinen 2004, p. 280 (fig.; U. Heinen); Belkin & Healy 2004, p. 309 (fig. 84c); Healy 1997, pp. 96–8, 192–3, 291 (fig. 114).

23 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1891-0414-860 (Aug. 2, 2020).

24 RKD, no. 106824: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106824 (Sept. 1, 2019); Gritsay & Babina 2008, pp. 275–6, no. 324; Martin 1972a, pp. 115–16, no. 23a; Jaffé 1989, p. 340, no. 1134; however other modelli related to this 1635 project could equally well have been modelli for a picture or tapestry: see for instance the modello of Frederick III, for sale at Christie’s, http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/paintings/sir-peter-paul-rubens-frederick-iii-holy-5520510-details.aspx (July 15, 2019).

25 Bober & Rubinstein 1986, pp. 96–7, no. 60; Haskell & Penny 1982, pp. 103–4, 130 (note 23).

26 F. Raussa in Borea & Gasparri 2000, ii, pp. 640–41, no. 5.

27 RKD, no. 2995200: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/2995200 (Aug. 25, 2020); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_H-2-91 (Aug. 2, 2020); Wouk & Morris 2016, p. 195, no. 54 ex. Fitzwilliam (K. W. Christian).

28 RKD, no. 295557: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295557 (Oct. 10, 2019); Belkin & Healy 2004, pp. 278–9, no. 70 (F. Healy).

29 Joconde (9 June 2014); Meyer zur Capellen 2001–, i (2001), pp. 162–5, no. 15.

30 http://comminfo.rutgers.edu/~mjoseph/CP/raff9.jpg (July 15, 2019); Jones & Penny 1983, pp. 188–9, fig. 200 (Cupid directing his servants).

31 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2006-U-412 (Aug. 2, 2020).

32 Wood 2010a, I, pp. 273–5, no. 42a, ii, fig. 110 (studio repetition); see also under no. 42 (lost painting by Rubens after Raphael), pp. 266–3; Clifford, Dick & Weston-Lewis 1994, pp. 106–7, no. 52; Jaffé 1989, p. 307, no. 926; Jaffé 1977, p. 28L, fig. 50 and col. pl. XV.

33 Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 186, fig. 69, under no 58 (the modello in Palazzo Pitti, Related works, no. 14a.I); Logan & Plomp 2004a, pp. 17 (fig. 12), 34 (note 56): Circle of Francesco Primaticcio (a drawing in red chalk that Rubens retouched); in the note Logan & Plomp refer to Meij & De Haan 2001 (see below) without mentioning that according to Meij the drawing was made by Rubens alone, and that he had not used an earlier drawing; Logan & Plomp 2004a, pp. 47 (fig. 29), 78 (note 65): von Rubens retuschierten Rötelzeichnung (a drawing in red chalk retouched by Rubens); Meij & De Haan 2001, pp. 116–19, no. 21 (Meij; Rubens); Wood 2000, pp. 155, 168 (notes 25, 31): according to Meij Rubens did not retouch an earlier drawing; Jaffé 1977, pl. XIV; Held 1959, i, pp. 161–2, no. 166, ii, fig. 172.

34 http://www.uffizi.org/artworks/la-primavera-allegory-of-spring-by-sandro-botticelli/ (July 15, 2019); Vergara 2001, pp. 40–41 (figs 10–11); Berti 1979, p. 177; Dempsey 1971.

35 Palluchini & Rossi 1982, i, fig. XXVII, p. 209, no. 373 (with three other allegories – Bacchus, Ariadne and Venus, Peace and Concord expel Mars and The Forge of Vulcan); a political allegory about the wise government of the Republic of Venice.

36 https://www.artic.edu/artworks/4089/venus-and-mars-with-cupid-and-the-three-graces-in-a-landscape (Aug. 26, 2020).

37 http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collect.150834 (July 16, 2019).

38 Büttner 2019, pp. 149–51, no. 5, fig. 77; McGrath 2016, pp. 467–9, no. 45a; Burchard & D’Hulst 1963, i, pp. 327–9, no. 205 verso, ii, fig. 205v. For the recto see Related works, no. 15a.Ia.

39 RKD, no. 199990: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/199990 (July 19, 2019); see also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/las-tres-gracias/ (July 19, 2019); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 964–7, no. 1670; Jaffé 1989, p. 366, no. 1344. According to Dequeker 2001 the central Grace shows S-shape scoliosis and a sign of Trendelenburg, a disease that was only described some centuries later, where the pelvis drops on the side opposite to the weight-bearing leg, see https://ard.bmj.com/content/60/9/894 (July 19, 2019). The question is whether Rubens had really seen these phenomena or exaggerated the forms for aesthetic reasons. In any case these ‘illnesses’ cannot be discerned in DPG264.

40 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1841-0809-47 (Aug. 2, 2020).

41 RKD, no. 108605: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/108605 (Sept. 1, 2019); Donovan 2004, p. 153 (fig. 96); Chiarini & Padovani 2003, ii, p. 352, no. 566 (M. Chiarini); letter of Peter Paul Rubens to Justus Sustermans, 12 March, 1638: seben mi ricordo, che V.S. trovera ancora nel suolo, di sotto I piedi di Marte, un libro, e qualche disegno in carta, per inferire che egli calca le belle lettere ed altre galanterie (translation in Magurn 1955, pp. 408–9: ‘I believe, if I remember rightly, that you will find on the ground under the feet of Mars a book as well as a drawing on paper [of the 3 Graces] to imply that he treads underfoot all the arts and letters’); see also Rosenthal 2005, p. 89, fig. 25.

42 http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/79d55423.html (July 19, 2019); Braham 1988, pp. 38–9, no. 42; Burchard & D’Hulst 1963, i, pp. 326–7, no. 204, ii, fig. 204.

43 Ducos 2013, pp. 206, 312, no. 148; Krempel 2007, pp. 20, 39 (fig.), 149, no. 3 (bronze replica of an ivory relief, basket missing, c. 1620); F. Healy in Belkin & Healy 2004, pp. 257–9, no. 62 (c. 1624); see also Watteeuw 2010, pp. 83–4 (fig. 13), 96 (note 107).

44 RKD, no. 263319: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/263319 (Sept. 1, 2019); Kräftner 2016, p. 144–7, no. 28 (C. Koch); Gaddi 2010, pp. 128–9, no. 21 (R. Trnek); Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 258–61, no. 65 (R. Trnek); F. Healy in Belkin & Healy 2004, p. 259 (fig. 62b), under no. 62 (Related works, no. 9b); Trnek 2000, pp. 50–53, no. 9, fig. 9 (1622–4); Mertens 1994, pp. 116–17, 132, fig. 47; Trnek 1989, p. 209.

45 RKD, no. 235021: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/235021 (Sept. 1, 2019); Belkin & Healy 2004, p. 259, fig. 62a; Cristina 2003, pp. 253–4, no. 124 (C. Frykland).

46 Meij & De Haan, p. 354, no. MB 5125.

47 K. Renger in Denk, Paul & Renger 2001, pp. 252–3, no. Z 20; Mielke & Winner 1977, pp. 106–10, no. 38 r.

48 RKD, no. 199983: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/199983 (Sept. 1, 2019); see also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-the-judgement-of-paris-1 (Sept. 1, 2019); Jaffé & McGrath 2005, pp. 58–9, no. 9 (see also pp. 60–61, nos 10 and 11 for later versions of this subject).

49 RKD, no. 50041: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/50041 (Sept. 2, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 112–16, no. 24 ; Neumeister 2009, pp. 306–7.

50 RKD, no. 64436: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/64436 (July 19, 2019); Joconde (5 June 2014); Foucart & Foucart-Walter 2009, p. 227, no. 1771.

51 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1981-0725-31 (Aug. 2, 2020); Jaffé 1983b, p. 118, fig. 5 (related to the Christ Church drawing for DPG264; Related works, no. 1); Logan 1987, p. 77, fig. 7, under nos 203–4 (the drawing in Warsaw; Related works, nos 15a.Ia and 8a).

52 RKD, no. 295224: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295224 (Oct. 10, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 186, fig. 80, under no. 58; Bodart 1990, p. 127 (fig.), under no. 43 (Related works, no. 14a.I).

53 RKD, no. 295222: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295222 (Oct. 10, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 186–8, no. 58 (F. Lammertse; c. 1630); McGrath 2016, i, p. 451, ii, fig. 395 (used by Van Opstal for Related works, no. 22a); Conticelli, Gennaioli & Sframeli 2017, p. 28 (fig. 13); Wieseman 2004, p. 50 (fig. 4); Rubens 2004, p. 105, no. 53 (H. Vlieghe); Chiarini & Padovani 2003, ii, pp. 354–5, no. 570; Gregori 1994, p. 517 (modello for an ivory object, before 1628–30); Bodart 1990, pp. 124–7, no. 43 compared this bozzetto with bronze statues by Giambologna and Adriaen de Vries, the work of Georg Petel and engravings by Goltzius and the stuccoes by Primaticcio at Fontainebleau, used for 11b; Jaffé 1989, p. 303, no. 896 (c. 1627–8); Held 1980, i, 327–8, no. 240, ii, fig. 255.

54 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1891-0414-872 (Aug. 2, 2020).

55 Büttner 2019, pp. 149–51, no. 5, fig. 77; Burchard & D’Hulst 1963, i, pp. 327–9, no. 205 recto, ii, fig. 205r. For the verso see Related works, no. 8a.

56 Büttner 2019, pp. 143–9, no. 4, fig. 64, where several copies are mentioned; Held 1980, i, pp. 412–13, no. 302, ii, pl. 302.

57 Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), pp. 100, no. 616.

58 RKD, no. 295558: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295558 (Oct. 10, 2019); see also https://www.teylersmuseum.nl/en/collection/art/kg-17669-de-drie-gratin (July 19, 2019). According to Büttner the print is probably by Remoldus Eynhoudt (1613–79/80): see Büttner 2019, under no. 4, print 1, pp. 144, 148 (note 7), fig. 67; Voorhelm Schneevogt 1873, p. 155, no. 151: (B. 44) Trois femmes, ayant assez de rapport avec les trois Grâces; elles se soutiennent l’une l’autre par les bras. Il y a cinq petits Amours, dont l’un couronne la Femme du milieu. Sans titre et sans nom de peintre ni de graveur. L’estampe est gravé à l’eau-forte dans la manière d’Eynhoudts. Dans la collection Teylerienne il y en a un exemplaire sur lequel est écruit: Rubens pinx. C. Schut sculpt. 8 p. 2 l. de haut, 9 p. 4 l. de large. T. (Bartsch 44; Three women, quite like the three Graces: they support one another with their arms. There are five little Cupids, one of whom crowns the woman in the middle. No title and and no name of painter or engraver. The print is an etching in the manner of Eynhoudts. In the Teyler collection there is a copy on which is written: Rubens pinx. C. Schut sculpt. 8 ft 2 in. h, 9 ft 4 in. w. In the Teylers collection); Rooses 1886–92, iii (1890), p. 100, no. 616: trois femmes […] Celle de droite donne le bras à celle du milieu et la tient par la main. Celle du milieu a passé le bras autour du cou de la troisième. La main de celle-ci est tenue par un petit amour. Deux autres petits génies précèdent le groupe; un quatrième l’accompagne en volant et tenant une couronne à la main. Le cinquième plane dans les airs et tient une couronne au-dessus de la tête de la femme du milieu. Cette dernière est évidemment le personage principal. Le sujet est peu clair. (Three women […] the one on the right holds the one in the middle and clasps her hand. The one in the middle has her arm around the neck of the third one. The hand of that one is held by a little cupid. Two other little spirits lead the group; a fourth one flies along with them and holds a crown in his hand. The fifth hovers in the air and holds a crown above the head of the middle woman. The latter is clearly the most important figure. The subject is not clear.) This description somewhat suggests the drawing by Panneels in Copenhagen (Related works, no. 13).

59 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1865-0311-177 (Aug. 2, 2020); Büttner 2019, under no. 4, print 2, p. 145, fig. 68; Voorhelm Schneevoogt 1873, p. 167, no. 114.

60 RKD, no. 266588: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/266588 (Sept. 2, 2019); Freedberg 1984, pp. 240–41, no. 53b, fig. 174; Held 1980, i, p. 327; Müller Hofstede 1965, pp. 168–70, no. 4, figs 7–8 (Lament for Deianera).

61 RKD, no. 261573: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/261573 (Sept. 2, 2019); Freedberg 1984, pp. 233–8, no. 53, fig. 170.

62 RKD, no. 239632: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/239632 (Sept. 2, 2019); see also https://www.fine-arts-museum.be/nl/de-collectie/peter-paul-rubens-de-geboorte-van-venus?letter=r&artist=rubens-peter-paul-1 (July 19, 2019); Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 254–5, no. 103 (B. Schepers); Jaffé 1989, p. 364, no. 1329; KMSKB 1984, p. 251, no. 4106; Held 1980, i, pp. 298–9, no. 217 (1636), ii, pl. 226; Alpers 1971, pp. 264–5, no. 58, fig. 186.

63 RKD, no. 248530: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/248530 (Sept. 2, 2019); see also https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/nacimiento-de-venus/ (July 19, 2019); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 1530–31, no. 1862; Jaffé 1989, p. 364, no. 1330; Alpers 1971, p. 265, no. 58a, fig. 188.

64 www.khm.at/de/object/1c54985e4f/ (July 19, 2019); Büttner 2019, under no. 10, p. 203, 208 (note 54), figs 22, 126, 128, 157; Kräftner, Seipel & Trnek 2005, pp. 348–55, no. 88 (A. Wied); Jaffé 1989, pp. 365–6, no. 1341.

65 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1885-0509-50 (Aug. 2, 2020); Büttner 2019, pp. 210–15, nos 10a, 10b, figs 143, 144, 146, 148; Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 280–83, no. 103; Logan & Plomp 2004b, pp. 486–9, no. 131.

66 Büttner 2019, pp. 193–210, no. 10, figs 125, 127, 139, 132, 140, 149; Joconde (15 Aug. 2014).

67 https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/galeria-on-line/galeria-on-line/obra/danza-de-aldeanos/ (Aug. 15, 2014); Büttner 2019, pp. 215–30, no. 11, figs 150, 153, 158; Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 28, fig. 18; Uppenkamp & Van Beneden 2011, p. 69, fig. 85; Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 988–91, no. 1691.

68 RKD, no. 245155: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/245155 (Sept. 2, 2019); D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 82–3 under no. 20, fig. 49. This picture seems to be a copy after another picture of which only two fragments exist. Rubens scholars do not agree whether the original design was by Rubens. Only Michael Jaffé considers the picture in Karlsruhe to be by Rubens: Jaffé 1989, p. 351, no. 1221. See also Held 1980, i, p. 634, no. A19 (under ‘Questionable and rejected attributions’), ii, pl. 489.

69 RKD, no. 269044: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/269044 (Sept. 2, 2019); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 28, fig. 18; Büttner & Heinen 2004, pp. 138–41, no. 11 (U. Heinen); Díaz Padrón 1996, ii, pp. 1096–9, no. 1665.

70 RKD, no. 295560: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295560 (Oct. 10, 2019); see also http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/877c8dbb.html (July 19, 2019), where the title is The Triumph of Silenius (sic); Held 1980, i, pp. 354–5, no. 264/4, ii, pl. 452. Held considers all existing versions to be copies after an original by Rubens.

71 Boudon-Machuel 2005, p. 106 (fig. 7).

72 http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&AMuseo=MNAD&Ninv=CE17828 (July 19, 2019); see also Malgouyres 2007, pp. 51–3, figs 11–14.

73 http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/lot/panse-de-chope-representant-les-trois-attribuee-5171589-details.aspx?intobjectid=5171589 (July 19, 2019); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 203, fig. 32, under DPG264.

74 According to McGrath (undated typescript in DPG264 file, ‘Rubens and the Graces’) Burchard attributed DPG264 to Jan Boeckhorst, which she considers unconvincing: p. 12 (note 37). Ludwig Burchard (RUB, LB no. 680–683 file): aus der Nachfolge des Rubens, nicht von seiner Erfindung (made by a follower of Rubens, not his own invention). And on a postcard and a reproduction of DPG264 in this file he had written ‘Boeckhorst’.

75 McGrath (undated typescript in DPG264 file, ‘Rubens and the Graces’) also says that in 1989 Held expressed the view (orally) that this drawing might be by Van Dyck.

76 Email from Elizabeth McGrath to Xavier Bray, 4 Nov. 2011 (DPG264 file).

77 Email from Elizabeth McGrath to Michiel Jonker, 10 Jan. 2012 (DPG264 file). According to Seelig (2017, pp. 100, 114 (note 65)) the modello in the NG (Related works, no. 2a) is Rubens’s only design for a silver object.

78 Nico Van Hout in conversation in the Rubenianum, Antwerp, 9 March 2015.

79 Burchard 1950, pp. 18–19, no. 16; see also Held 1980, i, p. 360.

80 Arnout Balis has drawn attention to the fact that a certain Van Opstal bought an ivory at the sale after Rubens’s death: see McGrath 2016, i, pp. 451, 454 (notes 24–30). Moreover, in the inventory of the widow of Johannes van Mildert four oil sketches by Rubens are mentioned (Lammertse & Vergara 2018, p. 186), so Van Opstal might have had access to Rubens sketches through his father-in-law.

81 About the three Graces in Antiquity see Bober & Rubinstein 1986, pp. 96–7, no. 60; Mertens 1994 discusses the theme in general in text and image; about Venus and the Three Graces see Balis 2006; about Rubens and the Three Graces see Vergara 2001 and McGrath 2016, i, pp. 449–55.

82 Balis 2006, p. 620.

83 See note 41 (Sustermans).

84 Balis 2006, p. 617.

85 Although they are not really dancing as Held contends, Held 1980, i, p. 327. Held refers to a picture in the United States (Related works, no. 7b.II). However the part with the Graces seems to be derived from the picture in Venice (Related works, no. 7b.I).

86 On Titian’s poesie see Wethey 1969–75, iii (1975), pp. 71–84.

87 Krempel 2007; Scholten 2006, pp. 37–44, 51–2; Müller & Schädler 1964.

88 According to Scholten Rubens was here competing with Petel on the question whether painting or sculpture was better in depicting reality (this competition between different art forms about mutual merits and superiority is called paragone): see Scholten 2006, p. 38.

89 See notes 7 (Patmore 1824b), 8 (Carson 1831–3) and 11 (Lavice 1867).