After Rubens DGP130, DPG403, DPG630

Manner of Rubens or after Rubens?

DPG130 – Virgin and Child

18th century; oak panel, 32.1 x 26.7 cm

PROVENANCE

?;1 Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 13, no. 109 (‘Stair Case contd / no. 31, Virgin & Child in a landscape – P[anel] Rubens’; 1'10" x 1'8").

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 8, no. 123 (‘SECOND ROOM – West side; The Virgin and Child; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, p. 381, no. 123;2 Cat. 1820, p. 8, no. 123; Cat. 1830, p. 9, no. 172; Denning 1858 and 1859, no. 172 (after Rubens); Sparkes 1876, p. 151, no. 172 (After P. P. Rubens);3 Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 143, no. 172 (under ‘old copies after Rubens’); Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 33, no. 130; Richter & Sparkes 1905, p. 33; Cook 1914, p. 77; Cook 1926, p. 73; Cat. 1953, p. 35; Murray 1980a, p. 299; Beresford 1998, p. 215; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 210, 215; RKD, no. 294870: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294870 (Aug. 6, 2019).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Two-member oak panel with a horizontal join. There is a piece missing from the top member at the verso right of the join. The panel was rejoined in 1993 and the losses and splits along the central join were filled and retouched at the same time. Fine network drying cracks are visible, particularly in the dark areas around the figures in the top third of the painting. The paint of the landscape on the proper right of the Virgin has the appearance of a discoloured copper green. The paint surface shows some abrasion due to past overcleaning. Previous recorded treatment: 1993, conserved, Courtauld Institute of Art.

RELATED WORKS

1a) (after?) Peter Paul Rubens, The Holy Family, panel, 104.5 x 73 cm. Crocker collection, San Francisco (burnt in 1906) [1].4

1b) Peter Paul Rubens, Holy Family with an Angel offering a Bowl of Fruit, c. 1628, canvas, 118 x 167 cm. Ruzicka-Stiftung, Kunsthaus, Zürich, R 55 [2].5

2a.I) Peter Paul Rubens and studio, The Holy Family with St Elizabeth and St John the Baptist (Madonna with the Goldfinch), c. 1634, canvas, 121 x 102 cm. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, Cologne, 1038 [3].6

2a.II) (in reverse and enlarged on all four sides) Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert after Peter Paul Rubens, The Holy Family with the Goldfinch, inscriptions, engraving, 39.9 x 31 cm. BM, London, 1841,0809.33.7

2a.III) Style of Rubens (previously School of Peter Paul Rubens) probably after 2a.I, Virgin and Child, panel, 90.5 x 69.8 cm. Holburne Museum of Art, Bath, A256.8

This small painting is likely to be an 18th-century picture in the manner of Rubens. According to Hans Vlieghe it draws its inspiration from Rubens’s Holy Family, formerly in the Crocker collection, San Francisco (burnt in 1906; Related works, no. 1a) [1].9 In that picture the child is looking archly at us, sitting on a white cushion, while his mother looks towards him; based on photographs, she seems to have one bare breast. DPG130 excludes the figure of Joseph and lets the Virgin look at us, just as her son does. A landscape is added at the left. Another source may have been a composition like the picture now in Cologne with a larger group, called Madonna with the Goldfinch, which includes the figures of St Elisabeth and St John the Baptist (Related works, no. 2a.I) [3]. In that picture the child is looking at us, and one of the breasts of his mother is shown.10 In this composition the figure of the Madonna looks more like the one in DPG130 (the heads of the Madonna and Child form one line) than the one in the Crocker picture (where they form more or less a triangle). The pose of the child is different position from that in the Crocker composition: he is seated with his left side towards us, and his left leg hides most of his right leg. In the print by Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert both the breast of the Madonna and the back of St John are covered (Related works, no. 2a.II). These pictures (and the print) all have an upright format. In the picture now in Zürich, with a landscape format, a landscape and an angel offering a bowl of fruit are added to the Holy Family, and the Madonna looks at the angel (Related works, no. 1b) [2]; the child has the same pose as in DPG130 and the Crocker picture. In every case the child looks at us; his mother does that as well only in DPG130.

The provenance of DPG130 is unclear, and is not likely to become clearer, since there were very many Madonna and Child pictures attributed to Rubens on the London market in the late 18th and early 10th centuries.

DPG130

after Peter Paul Rubens

Virgin and Child, 1700-1799

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG130

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Holy family

panel, oil paint 104,5 x 73 cm

San Francisco (California), collection Crocke (lost in fire in 1906)

2

Peter Paul Rubens

Holy Family with an angel offering a bowl of fruit, c. 1628

Zürich, Kunsthaus Zürich - Stiftung Prof. Dr. L. Ruzicka, inv./cat.nr. R 55

3

Peter Paul Rubens

Holy Family with Elisabeth and John the Baptist as a child with a hammer, c. 1634

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, inv./cat.nr. 1038

After Rubens

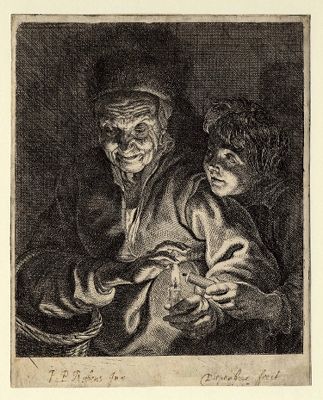

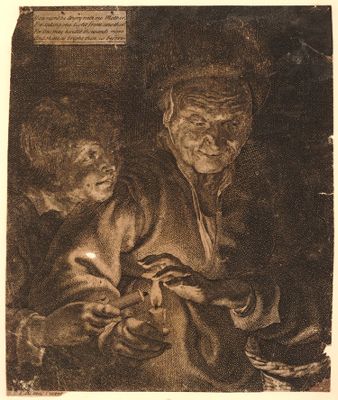

DPG403 – A Boy lighting a Candle from one held by an Old Woman

19th century?; canvas, 44.5 x 36.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Rev. John Vane, Second Fellow of Dulwich College, 1818–30; his gift, c. 1830. This seems to be wrong, see under references, where this picture seems to have been restored by Robert Brown in 1817.

REFERENCES

Brown Ledger, 15 March and 15 July 1817: ‘D.o [Lin.g Cleang Stip.g &c.] a pic.r of an Old woman holding a Candle &c after Rubins; - 18s’; Sparkes & Carver 1890, p. 41, no. 97 (after Rubens); Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 114, no. 403 (after Rubens); Cook 1914, p. 234; Cook 1926, p. 217; Cat. 1953, p. 35; Murray 1980a, p. 302 (Schalken [sic]); Beresford 1998, pp. 214–15 (after Rubens); Van der Ploeg 2005 (about Related works, no. 1) [4]; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 211, 215; RKD, no. 294817: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294817 (Aug. 1, 2019).

TECHNICAL NOTES

The support is fine plain-weave linen canvas, lined onto medium similar; the original tacking margins are present. There is an inscription on the verso: ‘DH College, the gift of the Revd John Vane’. The paint is smooth, flat and in generally good condition. There are two rubbed scratches near the right side, which have been consolidated and retouched. The faces are very slightly abraded, showing signs of past cleaning. There is an indentation around the outside of the image, about 1.5 cm in from the edges, from either a frame or an old stretcher. Although for the most part the paint has been fairly thinly applied, there is some impasto on the flame, the facial highlights and the woman’s white undergarment; this has mostly been flattened by the lining process. Previous recorded treatment: 1817, Robert Brown, see under References; 1953–5, conserved, Dr Hell; 1988, examined, Courtauld Institute of Art; 1990, cleaned, scratches retouched with watercolour, N. Ryder.

RELATED WORKS

1) Prime version?: Peter Paul Rubens, An Old Woman and a Boy in Candlelight, c. 1616–17, panel, 74 x 82.5 cm (before 1948: 95.2 x 82.5 cm). MH, The Hague, 1150 [4].11

2a) Peter Paul Rubens retouched by Jacques Ignatius de Roore (?), Die Alte mit dem Kohlenbecken (The old woman with the brazier), c. 1616–18, panel, 115.5 x 92 cm (originally c. 108 x 87 cm). Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, 1560 (Gal. no. 958).12 Originally combined with the picture that is now Rubens’s Venus in Vulcan’s Smithy in Brussels (previously Sine Cerere et Libero friget Venus), see DPG165, Related works, no. 6.

2b) Copy: by Rubens’s studio of Peter Paul Rubens (DPG165, Related works, no. 6), Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus, canvas, 184.9 x 203.3 cm. MH, The Hague, 247 [5].13

Prints

3a) (in reverse; boy on the right) Peter Paul Rubens? (attribution controversial), Paulus Pontius or Abraham van Diepenbeeck (?) after Peter Paul Rubens (no. 1), An Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, c. 1620–30, inscriptions, etching (first state), 247 x 198 mm. BM, London, S.7262 [6].14

3b) (same direction as no. 1; boy on the left) Peter Paul Rubens and Paulus Pontius (?), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, engraving, second state (3), contre-épreuve, retouched and annotated by Rubens, 246 x 201 mm. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Cc 34., C 10510.15

3c) (same direction as 3a; boy on the right) attributed to Raimondo della Croce after Peter Paul Rubens’s print (3a), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, dated 1706, pen in brown in engraving technique, 259 x 197 mm. Uffizi, Florence, 8845 S.16

4a) (again in reverse, so in the same direction as Related works, no. 1; boy on the left) Jakob Stahl after Peter Paul Rubens’s print (3), An Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, Latin inscriptions (same as in the second state of 3a–b) and two extra lines, dated 1646, published in Riga, etching, 244 x 203 mm. BM, London, S.6718.17

4b) (same direction as no. 1; boy on the left) Francis Wheatley after Godefridus Schalcken (‘in the possession of George Rogers’) after Peter Paul Rubens (5a), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, c. 1760–70, mezzotint, 324 x 230 mm. BM, London, 1901,0611.24.18

4c) (same direction as no. 1; boy on the left) Joshua London after Peter Paul Rubens, Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, c. 1680–1720, inscriptions, mezzotint, 212 x 157 mm. BM, London, S.7685.19

4d) (same direction as no. 1; boy on the left) Jacques Meheux after Peter Paul Rubens, Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, mezzotint, 230 (trimmed) x 217 mm (trimmed). BM, London, 2000,U.14.20

4e) (same direction as no. 1; boy on the left) ?Cornelis Visscher II after Peter Paul Rubens’s print (3), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, etching, 217 × 190 mm. Lent by Fondation Lucas van Leyden to BvB, Rotterdam, BdH 5719 (PK).21

4f) (same direction as no. 1; boy on the left) Pieter Soutman after Peter Paul Rubens (no. 1), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, inscriptions (see text), etching, 209 (trimmed) x 177 mm. BM, London, S.6719 [7].22

5a) (study for 5b; boy on the right) Willem Panneels, Cursus Mundi (Course of the world), c. 1631, inscriptions in Latin, red chalk, pen, brown and black ink, brush, white bodycolour on yellowish paper, c. 242 x 164/168 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, 258r.23

5b) (in reverse; boy on the left) Willem Panneels after no. 5a, Cursus Mundi, inscriptions in Latin, etching, 243 x 171 mm. BM, London, R,4.87.24

‘Godefridus Schalcken’

6a) Godefridus Schalcken (?) after the print by Peter Paul Rubens (3a; boy on the right), panel, 30.1 x 24 cm. Narodni Museum, Warsaw, no. 1152 (inv. 120).25

6b) After Godefridus Schalcken (?) (6a) after Peter Paul Rubens (3a; boy on the right), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, panel, 40.5 x 30.2 cm (estimate). Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, TWCMS:B6228 (previously SAG 229).26

6c) Circle of Godefridus Schalcken (?) after Peter Paul Rubens (3a–b; boy on the right), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, monogram on basket S, panel, 43.3 x 31.3 cm (estimate). Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, BATVG:P:1934.4.27

6d) Follower of Godefridus Schalcken (?) after Peter Paul Rubens (3a; boy on the left according to Beherman), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, panel, 39 x 32.3 cm. KMSKB, Brussels, 8503.28

6e) Follower of Godefridus Schalcken (?) after Peter Paul Rubens (3a–b; boy on the right), Old Woman and a Boy with Candles, panel, 31 x 41 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (‘Oudt Holland’ gallery, The Hague, 1943; Photo RKD).29

Scenes with candles by other artists

7) El Greco, Boy lighting a Candle, c. 1570–75, canvas 60.5 x 50.5 cm. Farnese collection, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Q 192.30

8) Jan Lievens, Boy with Brazier and Two Candles (part of a series of the Four Elements/Ages: Fire=Youth), c. 1623–5, panel, 83 x 58.2 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel, GK 1205.31

9) Jacques Jordaens I, ‘The light once loved by me, I give, dear child, to thee’, 1640s (?), pen and brush and brown ink and indigo, over black chalk, 130 x 200 mm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, 14.233.32

DPG403

after Peter Paul Rubens

Boy lighting a Candle from one held by an Old Woman, after 1617

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG403

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Old woman and boy in candlelight, c. 1616-1617

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 1150

5

after Peter Paul Rubens

Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus, 17th century

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 247

6

Abraham van Diepenbeeck after Peter Paul Rubens

Old woman and a boy with candles

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. S.7262

7

Pieter Soutman after Peter Paul Rubens

Old woman and a boy with candles, 1620-1657

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. S.6719

DPG403 is a (19th-century?, British?) copy of an original nightpiece by Rubens that he painted c. 1616–17. The original picture, or at least the best version of the survivors, was acquired by the Mauritshuis in 2005 (Related works, no. 1) [4]. That may be the version of the picture that was still in Rubens’s collection at the time of his death,33 although Rubens and his studio are known to have made many successful compositions, in both painted and printed form. DPG403 might have been made after the painting in the Mauritshuis that, as usual for Rubens, consists of several pieces of wood.34 Another possibility is that DPG403 was painted after one of the later prints, which are in the same direction as the original picture, of which the one by ‘Cornelis Visscher II’ (c. 1628/9–58) is the most likely (Related works, no. 4e). Many prints were made after the original composition, some supervised by Rubens, which are in reverse (Related works, nos 3a–b) [6], and some by later printmakers, who used Rubens’s print as their model; these are consequently in the same direction as the original painting (Related works, nos 4a–f) [7].35 We can follow the way Rubens supervised the genesis of the print that started out as an etching and ended as an engraving by Paulus Pontius, as analysed by Hind in 1923.36

In 1980 Murray attributed DPG403 to Godefridus Schalcken (1643–1706), and it is may be significant that in the 18th century Francis Wheatley (1747–1801) produced a similar mezzotint after a painting by Godefridus Schalcken in the collection of George Rogers (Related works, no. 4b). Although DPG403 is clearly not by Schalcken, it seems that that artist produced one copy in the manner of Rubens now in Warsaw, at least according to Beherman in his œuvre catalogue of Schalcken (Related works, no. 6a). There are further copies from ‘Schalcken’s circle’, for instance in the Shipley Art Gallery in Gateshead, Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, and Musée des Beaux-Arts in Brussels (Related works, nos 6b–d). Interestingly, in the entries on these ‘Schalcken’ pictures in Bath and Gateshead no reference is made to Rubens. In contrast, according to Ger Luijten, the Schalcken signature on the Brussels copy is apocryphal; he rejects all attributions to Schalcken, as did Hind in 1923.37 Schalcken is also mentioned as the copyist after the Elsheimer scene with Ceres at the Cottage (DPG191), of which a version was once in Rubens’s possession (see below).

A proof of the second state of the original Rubens/Pontius print, in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris (Related works, no. 3b), is inscribed, apparently in Rubens’ hand:

Quis vetet apposito, lumen de lumine tolli

Mille licet capiant, deperit inde nihil

(Who can forbid getting light from another light that is near? Light can be taken a thousand times from another light without diminishing it.)

That text can be found under many of the prints. On the latest state of the etching made by Pieter Soutman (Related works, no. 4f) [7], probably after the print by Pontius after Rubens, there is also an inscription, in this case in English, which is a very free translation of the Latin:

You won’t be angry with me, mother,

For taking one light from another?

For one may kindle thousands more

And shine as brightly as before.

It is possible that Soutman, who worked in Antwerp and Haarlem, added these English verses; another possibility is that Soutman’s copperplate had found its way to England, and was there provided with a new text.38 In any case it is clear that the image of the old woman and the boy with candles was popular in Europe. Copies were made as far away as Riga and Florence, but especially in England.

DPG403

after Peter Paul Rubens

Boy lighting a Candle from one held by an Old Woman, after 1617

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG403

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Old woman and boy in candlelight, c. 1616-1617

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 1150

6

Abraham van Diepenbeeck after Peter Paul Rubens

Old woman and a boy with candles

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. S.7262

7

Pieter Soutman after Peter Paul Rubens

Old woman and a boy with candles, 1620-1657

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. S.6719

The Latin lines are from Ovid’s Ars amatoria.39 They give the clue to the interpretation of the scene which shows an old woman holding a candle and a boy about to light his candle from hers. Ovid especially encourages young women to have many lovers, taking the Roman goddesses as their examples, so that they do not have to look back on an unfulfilled life, as the old woman does in the cold of the night.40 The boy is about to take a light from her. The message is: seize the day in sexual matters. A very similar scene, of an old woman warming her hands on a brazier and an older and a younger boy, was created by Rubens in a composition entitled Sine Cerere and Baccho Venus friget, of which only copies exist, including one in the Mauritshuis (Related works, no. 2b) [5]. Rubens himself had removed the part with the old woman, which is now in Dresden (Related works, no. 2a), and replaced it with a scene with Vulcan’s smithy (see under DPG165, Related works, no. 6).41 Also in the original composition the old woman is shown with her wrinkles contrasting with the smooth skin of the two boys in the light of the brazier. And the old woman is depicted as part of a scene that has an erotic meaning (see under DPG165 for the interpretation). She is a stock type that occurs frequently in Rubens’s œuvre. It is one of the first candle-light compositions that became so popular in 17th-century Northern European painting (e.g. in works by Gerard van Honthorst and Godefridus Schalcken).42 We find nightpieces in the 15th-century Netherlands, such as The Nativity at Night by Geertgen tot Sint Jans (1455/65–85/95),43 and in Italy, for instance by Caravaggio (1571–1610) and Elsheimer. Rubens is known to have sold the Spanish King four pictures by Elsheimer, of which a night scene with Ceres at the Cottage is now in the Prado (see DPG191, Related works, no. 1b). Even earlier than Rubens, El Greco made a picture with a boy with a candle in Rome c. 1570–75 (Related works, no. 7). It is not impossible that Rubens had seen that in Rome, since it was in the Farnese Palace until 1622.44 On the other hand, Rubens could have read Pliny (Historia naturalis (XXXIV.79, XXXV.138), where there are descriptions of boys depicted by Antique painters by night, with the reflections of a fire on their faces.45

Willem Panneels, who was left in charge of Rubens’s studio while the master was away (1628–30), made a print where a skeleton is added to the old woman and the boy, who have as their attributes both a candle and a brazier. The boy is blowing in the brazier; Panneels stressed the message of transiency with the title Cursus Mundi (the course of life; Related works, no. 5b). Jan Lievens incorporated a boy blowing in a brazier and lighting one candle from another in a series of the Elements and Ages, in this case Fire and Youth (Related works, no. 7). Jacques Jordaens used the motif with the candles in a much more innocent way, illustrating the Dutch proverb Het licht weleer bij mij bemind, dat geef ik u, mijn waarde kind (The light once loved by me, I give, dear child, to thee). In that scene three generations are present: grandfather and grandmother, a father and a mother and a child. The mother opens a lantern so the child can light a candle: the light symbolizes life and virtue passed on from one generation to another (Related works, no. 9).

5

after Peter Paul Rubens

Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus, 17th century

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 247

After Rubens

DPG630 – The Judgement of Paris

19th century; canvas, 95 x 127 cm

PROVENANCE

Anonymous Gift, 1955.

REFERENCES

Murray 1980a, p. 305 (copy after Rubens); Beresford 1998, pp. 214–15; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 211; RKD no. 294805: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294805 (Aug. 1, 2019).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Plain-weave glue-lined linen canvas; the tacking margins have been cut and the painting is approximately 1.4 cm narrower than the stretcher. The canvas has been slightly scorched during a previous lining, and the lining is frail at the edges. There is evidence of bitumen in the shadows and figures. The fine, all-over craquelure of the surface is worse and more visible in the draperies. Previous recorded treatment: 1994, weak edges reinforced, S. Plender and N. Ryder.

RELATED WORKS

1) Prime version: Peter Paul Rubens, The Judgement of Paris, c. 1632–5, panel, 144.8 x 193.7 cm. NG, London, NG194 [8].46

2) Workshop replica: The Judgement of Paris, c. 1635, panel, 49 x 63 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, 1574.47

3) Copy: G. von Beringe, The Judgement of Paris, signed and dated 1922, canvas, 49.5 x 64 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Dorotheum, Vienna, 7 June 2000, lot 416).48

DPG630 is a copy of Rubens’s original in the National Gallery, London (Related works, no. 1) [8], and probably dates from the 19th century. A poor quality work, in an even worse state of conservation, the picture was given to the Gallery by an anonymous donor in 1955. The scene depicts Lucian’s ‘Judgement of the Goddesses’ (Dialogues of the Gods, 20), where Paris presents a golden apple to Venus as the most beautiful of the three goddesses. For another depiction of this subject see DPG147 (Adriaen van der Werff). Venus stands between Minerva and Juno; behind Paris to the right is Mercury. Above is the Fury, Alecto; there is a winged cupid in the lower left. There is a peacock at Juno’s feet, and Minerva stands before her armour. Rubens was no doubt attracted to the subject by the opportunity to depict three beautiful women in a state of undress; he made several versions of the Judgement of Paris, and also The Three Graces, a closely related subject (DPG264 and its Related works).

DPG630

after Peter Paul Rubens

Judgement of Paris, 1800-1899

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG630

8

Peter Paul Rubens

The judgement of Paris, 1632-1635

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG194

Notes

1 DPG130 was probably not in Desenfans’ private sale, 8ff June 1786 (Lugt 4059A), lot 152 (‘Rubens – Madona [sic] and child’ ‘2'10" x 2'6" [includes the frame]’ or Christies, 14 July 1786 (Lugt 4071), lot 25 (‘Rubens – A madona [sic] and child’). Bt Maden (sold or bought in), £0.19: that picture seems to be much larger than DPG130.

2 ‘SIR P. P.RUBENS. The Virgin and Child. Sweetly and naturally coloured, the carnations perfect flesh; but have more the identity and individuality of real life, or portraits of any mother and child. No divinity is expressed or attempted in either; nor is the drapery, though fine, the drapery of a Madonna, which is almost a prescription; but is a glowing and richly-diversified scarlet; the breast, which is exposed, though lovely, is too full, and the face too motherly for the virgin character of the Madonna.’

3 ‘A feebly-painted Flemish mother’.

4 RKD, no. 22316: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22316 (July 29, 2019); Rosenberg 1905, pp. 281, 449 (from the Duke of Marlborough collection, Blenheim, sale 1886); Oldenbourg 1921, pp. 443, 472 (Die Eigenhandigkeid […] steht nicht außer Frage (The authenticity is questionable)); not in Corpus; not in Jaffé 1989.

5 RKD, no. 294916: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294916 (Aug. 7, 2019); Klemm & Lentzsch 2007, p. 94; Puttfarken 2004, pp. 84–5, no. 3 (Klemm); Jaffé 1989, pp. 329–30, no. 1062.

6 RKD, no. 22493: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/22493 (Aug. 2, 2019); Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 267–8, no. 111 (B. Schepers in association with H. Dubois); not in Jaffé 1989; Schepers refers to Vlieghe 1987b, pp. 93–4, no. 98, where however the Cologne picture is not mentioned. For a 17th-century copy now in Brussels see Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 267–8, no. 112 (B. Schepers) (NB: the illustrations of nos 111 and 112 in this publication seem to be confused).

7 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1841-0809-33 (Aug. 2, 2020); first state before the publisher’s address. For another impression and comment see BM, London, R,4.8.

8 S. Steer in NICEP https://www.vads.ac.uk/digital/collection/NIRP/id/32482/rec/1 (Jan. 21, 2021).

9 Letter from Hans Vlieghe to Richard Beresford, 23 Sept. 1997 (DPG130 file).

10 It has been suggested that the child looks like the son of Rubens and Hélène, Frans. For portraits of Frans Rubens as a child see Vlieghe 1987b, pp. 93–8, nos 98–9c, figs 92–102.

11 RKD, no. 62554: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/62554 (July 19, 2019). Provenance: ?Inventory P. P. Rubens, Antwerp, 1640, no. 125 (Vn Pourtrait d’vne vieille auec vn garcon à la nuict (Portrait of an old woman, with a boy by night); see Muller 1989, p. 118); possibly in the collection of Arnold Lunden, Rubens’s brother-in-law, in the 1640s: No. 164, Une femme avec un Enfant par Rubens (Muller 1989, p. 118, no. 125 (note 1): ‘the description […] is too vague to allow for any certainty’; see Vlieghe 1977c, pp. 200–201 (fig. 22); sale Hastings Elwyn, Phillips, London, 23 May 1806 (Lugt 7101), lot 27, to Delahante, by whom sold to Charles Duncombe (1764–1841), created 1st Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park in 1826; Charles ‘Sim’ William Slingsby Duncombe (1906–63), 5th Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park and 3rd and last Earl of Feversham of Ryedale; sold in 1947 to Francis Francis, Bird Cay, Bahamas (1947–65 on loan to MFA, Boston); sale, Sotheby’s, 30 June 1965, lot 15, for £19,000 to Agnew’s; unknown private collection; sale, Sotheby’s, 7 July 2004, lot 30; Otto Naumann Ltd, New York; MH, The Hague, 1150. Van der Ploeg 2005 includes under the provenance the Muhlmann collection, Riga, in 1646, and George Rogers (before 1801). However in Riga only a print after Rubens must have been available, and Muhlmann was probably the publisher of the print (see the print by Stahl, Related works, no. 4a). In the case of the Rogers collection, as mentioned in Related works, no. 4b, it was probably one of the ‘Schalcken’ pictures (Related works, no. 6a–e). For the picture in the Mauritshuis see also Van Hout 2004b, p. 75 (note 9); Davies 1989, pp. 76–7, no. 25 (‘In spite of its apparently sinister mood […] the meaning of Rubens’ picture, is by contrast [to the pictures by El Greco cat. nos 14–16, pp. 54–6] innocuous’) [the cat. nos show a girl blowing on fire to light a candle – with a monkey and a simpleton); Jaffé 1989, pp. 228–9, no. 430 (whereabouts unknown); Evers 1943, pp. 233–4, fig. 235; Rooses 1886–92, iv (1890), pp. 91–3, no. 862 (collection de Lord Feversham), panel 102 x 81, pl. 275 (= print by P. P. Rubens and Vorsterman or Pontius).

12 RKD, no. 46666: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/46666 (July 29, 2019); Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 274–9, no. 116 (B. Schepers and H. Dubois); Marx 2005–6, ii (2006), p. 452, no. 1560 (Gal. no. 958), i, p. 458 (U. Neidhardt); Schnackenburg 2005, p. 123; Stewart 2004, pp. 195, 196, 199 (who sees the portrait of Jan Lievens in the boy/man on the left, allegedly made during Lievens’s visit to Antwerp in 1620–21; Jaffé 1989, p. 228, no. 429B. See also for a print after this picture Brakensiek & Polfer 2009, pp. 122-123, no. 032 (S. Brakensiek).

13 RKD, no. 72069: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/72069 (July 31, 2019); Büttner 2018a, i, p. 388–9, copy no. 3, ii, fig. 256; B. Schepers and H. Dubois in Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 274–9, no. 117 (Allegory of the youthful and fertile love? Copy of an assemblage of the previous cat. nos 115–16); Buvelot 2004, p. 274, no. 247.

14 RKD, no. 294833: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/294833 (Aug. 7, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Sheepshanks-7262 (Aug. 2, 2020); for the second state see R,4.86 and 1868,0822.797 (retouched with burin by Pontius). According to Barrett (2012, pp. 49–50, 331 (fig. 14)) this second state was made by Rubens (with Soutman and Vorsterman or Pontius?). For a counterproof of the first state see R,4.88; Van Hout 2004b, pp. 71–3, 75 (notes), fig. 40; Mai & Vlieghe 1992, pp. 599–600, no. 190.2 (copy in Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, 16.234; P. Huvenne); De Jongh & Luijten 1997, pp. 209–12, under no. 40. Voorhelm Schneevogt 1873, p. 153, no. 134.

15 http://images.bnf.fr/jsp/index.jsp?destination=afficherListeCliches.jsp&origine=rechercherListeCliches.jsp&contexte=resultatRechercheSimple (Aug. 1, 2019); Van Hout 2004b, pp. 71–3, 75 (notes), fig. 42; De Jongh & Luijten 1997, pp. 209–12, under no. 40.

16 RKD, no. 33955: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/33955 (Aug. 1, 2019); Löffler 2000, pp. 215–16, no. TV 3 (under Rejected attributions to Theodor Vercruys).

17 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Sheepshanks-6718 (Aug. 2, 2020); see also Davies 1989, pp. 78–9, no. 26 [NB: the etching illustrated is not the one made by Stahl in Riga]; Voorhelm Schneevoogt 1873, p. 153, no. 136.

18 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1901-0611-24 (Aug. 2, 2020); Voorhelm Schneevoogt 1873, p. 153, no. 136bis.

19 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Sheepshanks-7685 (Aug. 2, 2020); Voorhelm Schneevoogt 1873, p. 153, no. 137.

20 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2000-U-14 (Aug. 2, 2020).

21 http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cornelis_Visscher_(II)_003.jpg (July 29, 2019). According to G. Luijten this is a deceptive copy in reverse, which was previously attributed to Cornelis Visscher. G. Luijten in De Jongh & Luijten 1997, p. 212 (note 17).

22 RKD, no. 295156: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/295156 (Aug. 31, 2019); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Sheepshanks-6719 (Aug. 2, 2020): ‘This is an undescribed impression with English lettering, for impression of earlier states see S.6717 and 2006,U.765. For comment on the plate by Rubens see S.7262’ (Related works, no. 3a).

23 Not on the website (2 Aug. 2014); Döring 1993, p. 258 (under no. 87; Related works, no. 4b); Kockelberg & Huvenne 1993, p. 44 (fig. 14); Garff & De la Fuente Pedersen 1988, i, pp. 190–92, ii, fig. 261.

24 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_R-4-87 (Aug. 2, 2020); Döring 1993, pp. 258–9, no. 87; Davies 1989, pp. 80–81, no. 27; Boon & Verbeek 1964, p. 126, no. 33 (3 states) with a skeleton.

25 Beherman 1988, p. 366, no. 349; Białostocki & Chudzikowski 1970, p. 98, no. 1152 (Inv. 120).

26 https://www.vads.ac.uk/digital/collection/NIRP/id/32296/rec/27 (Jan. 21, 2021; E. van der Beugel); Beherman 1988, p. 366 (fig. 349a).

27 https://www.vads.ac.uk/digital/collection/NIRP/id/28836/rec/12 (Jan. 21, 2021; S. Steer); Beherman 1988, p. 366, under no. 349.

28 https://www.fine-arts-museum.be/nl/de-collectie/anoniem-naar-peter-paul-rubens-vroegere-toeschrijving-navolger-van-godfried-schalcken-oude-vrouw-en-kind-een-kaars-aanstekend?letter=s&artist=schalcken-godfried-1 (July 31, 2019); KMSKB 1984, p. 267, 8503 (follower of Godfried Schalcken); Beherman 1988, p. 366 (fig. 349b).

29 Beherman 1988, p. 366, no. 349c (fig.).

30 This picture is recorded as being in the Farnese Palace in Rome until 1622; Cassani 1995 pp. 212–13 (P. L. de Castris); Davies 1989, pp. 52–3, no. 13; Wethey 1962, ii, pp. 78–9, no. 122; fig. 22; in Davies 1989 more scenes with candles by El Greco are mentioned.

31 Schnackenburg 1996a, i, p. 171, ii, pl. 115. Another version of this picture was in the Edinburgh exhibition in 1989, Davies 1989, pp. 86–7, no. 30.

32 D’Hulst 1974, i. pp. 295–6, no. A210, iii, fig. 225.

33 See note 10 above.

34 Van der Ploeg 2005, pp. 12–14, fig. 7.

35 Voorhelm Schneevoogt, p. 153, nos 134–41.

36 See the four stages as illustrated in Van Hout 2004b, p. 73; De Jongh & Luijten 1997, p. 210; Hind 1923, pp. 78–80 (figs pp. 71, 73, 75 and 77).

37 G. Luijten in De Jongh & Luijten 1997, p. 212 (note 17); Hind 1923, p. 80 (‘a natural error with a candle-light subject’). Beherman in his 1988 publication on Schalcken considers the Warsaw picture to be an original by Schalcken: Beherman 1988, p. 366, no. 349; he thinks the other copies are dues à l’entourage de Schalcken (made by the circle of Schalcken); he mentions the pictures in Gateshead, Bath, Brussels, and one formerly in The Hague. He too does not mention Rubens.

38 Hind 1923, pp. 79–80; Voorhelm Schneevoogt 1873, p. 153, no. 135.

39 Ovid, Ars amatoria (III.93, 90), found by Jan Bloemendal: see De Jongh & Luijten 1997, p. 212 (note 10). Under his 1646 print published in Riga (Related works, no. 4a) Jakob Stahl added two more lines in Latin: Cogniti sic artis, si tollis abore magista / Ars tamen ipsa manet scibile (?) nec minuus (?). These lines appear not to come from Ovid’s text: http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/ovid/ovid.artis3.shtml (Aug. 3, 2014). On that website Rubens’s ‘capiant’ and ‘tolli’ are replaced by ‘sumant’ and ‘sumi’. According to Davies (1989, p. 79) the lines Stahl added mean: ‘So, too, with the precepts of art – if you take them from the lips of a master his art itself still stays, no less teachable than before’.

40 Ovid, lines 69–70. G. Luijten in De Jongh & Luijten, p. 212 (note 14). pp. 155–6. In English translation: ‘Make the most of your youth; youth that flies apace. […] Thou who rejectest love, to-day art but a girl; but the time will come when, all alone and old, thou wilt shiver with cold through the long dark hours in thy solitary bed. […] Follow then, ye mortal maidens, in the footsteps of these goddesses; withhold not your favours from your ardent lovers. If they deceive you, wherein is your loss? All your charms remain; and even if a thousand should partake of them, those charms would still be unimpaired. […] Doth a torch lose aught of its brightness by giving flame to another torch?’ See pp. 155–6 in the translation by J. Lewis May (originally published in 1930), http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/ovid/ovid.artis3.shtml (Aug. 3, 2014).

41 On the complicated way the panels had to be strengthened see B. Schepers & H. Dubois in Vander Auwera, Vander Auwera, Van Sprang & Rossi-Schrimpf 2007, pp. 278–9 (figs 5–6).

42 About nightpieces see Neumeister 2003a, where strangely enough Rubens does not figure.

43 National Gallery, London, NG4081. Neumeister 2003a, pp. 21–3, fig. 1.

44 See note 11 above (Davies).

45 The Pliny quotations are mentioned in Białostocki 1988/1966, p. 144.

46 RKD, no. 197443: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/197443 (July 31, 2019); https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-the-judgement-of-paris/26781 (July 29, 2019); Martin 1970, pp. 153–63.

47 RKD, no. 46671: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/46671 (July 31, 2019); Marx 2005–6, ii (2006), p. 455, no. 1574 (Gal. no. 962B). Many more copies are mentioned in Martin 1970, p. 157.

48 RKD, no. 67544: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/67544 (July 31, 2019).